This week's "Back in the Day" item: live television covearge of an atom bomb blast.

It was called "Operation Q," the involvement of an NBC-CBS pooled crew of 95 technicians, engineers, announcers and photographers in Yucca Flat, Nevada*, for the planned detonation of an atomic bomb. The plan brought such media luminaries as Charles Collingwood, Dave Garroway, Walter Cronkite, John Cameron Swayze, Morgan Beatty, Sarah Churchill, and John Daly from New York to the frigid (28 degrees) site for an event that was to become "the highest rated show never to go on the air."

*Yes, the same Yucca Flat as in the immortal MST3K movie The Beast of Yucca Flats.

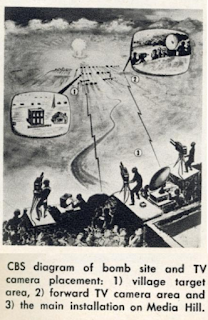

Collingwood (CBS) and Garroway (NBC) were there for their networks' respective morning shows, with the plan of showing not only the blast itself, but the instant reactions from those hunched in a trench less than two miles (!) from the 500-foot steel tower holding the bomb. The technicians had arrived five days ahead of the scheduled April 26 date to set up their equipment, including seven cameras and a microwave route to Las Vegas, from which the picture would be transmitted via cable to Los Angeles.

Only one problem with this carefully planned scenario: it doesn't happen. Apparently even the prospect of nuclear war is dependent on things being glitch-free, and Operation Q was far from that. The test was plagued with postponment after postponment, with each one causting the networks $5,000 per day, in addition to the original $80,000 setup cost. Finally, after the seventh postponment, the networks pulled the plug on the planned coverage; everyone headed home, leaving just one camera crew behind to cover the event, which finally came off on May 5.

You're probably quite familiar with this atomic bomb test; you've seen it many times, even if you weren't aware of it. This was the test in which the military built a replica town in Yucca Flat, complete with "furnished homes, industrial buildings, and clothed mannequins." The journalists covering the test called it "Doom Town," (I can see why that wasn't included in the TV Guide story.) The film of the explosion and its effect on the town have been a standard part of nuclear blast warnings ever since, and even after all these years pictures of it never fail to shock:

Life magazine did an extensive layout of the effecs of the test on Doom Town, which

you can see here. It's sobering, to say the least. It's also quite understandable that television would want to cover something like it; it was yet another example of the awesome power made availabe by science, and being unleashed by man. True, you could have seen it in a newsreel in your local theater, but the idea of bringing this into one's home to share with viewers—well, I suppose it was meant to be both frightening and reassuring at the same time. (Send a message to those Russkies, you know.) I'm not quite sure what today's equivalent would be.

l l l

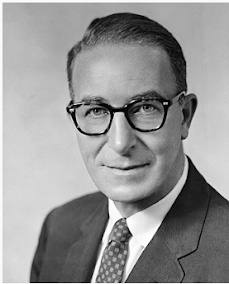

It would be nice if I had something clever to follow up with here, something like a story about the biggest television bombs of the year, but I'm afraid the best I can do is another story on the effect violent (but non-atomic) television has on children, this one by Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver. Kefauver, who previously garnered headlines for his investingation into organized crime, is now looking at juvenile deliquency, and while TV has been helpful in calling attention to this situation, there's still work to be done.

Understand, Kefauver is not a critic of television in the way that so many others are in the 1950s. Indeed, the medium has been very kind to him; television coverage of his committee's hearings on organized crime was a hit, catapulting him to national prominence (his victory in the 1952 New Hamphsire presidential primary encouraged President Harry Truman to drop out of the race), and the publicity for his deliquency hearings promises to keep him in the headlines. Personally, Kefauver and his family enjoy television, with practical restrictions. "In my family, there is one rule for all four of my children. They must do their homework before they are permitted to watch TV. Then they may watch till bedtime." The youngest aren't allowed to watch programs with violence, but his older kids (9 and 13) can watch whatever they want. "There are travelogs, historical shows, programs of news and current events. Generally speaking, television does a fine job."

This wouldn't be much of a story if all the news was good, though, and Kefauver insists that, for the recent progress television has made, there's still too much violence being portrayed. There are other effects that concern him as well; to those who claim that police shows like Dragnet teach kids that crime doesn't pay, Kefauver counters that it can send a mixed message. "The boy, in the training school for a relatively minor infraction, sometimes sits up and comments, 'Hey, I didn’t do anything nearly as bad as that and the law sent me here for even longer.' So those programs teach some boys they can commit lots worse offenses and pay no heavier penalty."

He also thinks that, while censorship is wrong, the government should be stronger in creating overall standards, and that stations violating the voluntary Code of Good Practice should be reported to the FCC. "It should be evidence to be considered at license renewal time." He also believes that too many producers of filmed shows subscribe to the Code, and that one answer might be for the industry to form a board of review, similar to that in existence for movies, which can issue a seal of approval for shows that comply with its guidelines.

I don't know; it sometimes gets tiresome looking at these stories on TV and violence. They come up so regularly, and after an initial flurry of activity nothing really seems to change. And ten years from now, in the mid-60s, we'll be talking about what effect Saturday mornng superhero cartoons have on kids. But it's a sign of the culture, of how important this issue seems to people, that it keeps coming up.

There's also something interesting about Kefauver and television; as I mentioned earlier, he was one of the first politicians to realize the potential for TV to expand the reach of candidates for high office. As in 1952, he's one of the front-runners for the Democratic presidential nomination again in 1956, again losing out to Adlai Stevenson. But when Stevenson leaves the choice of running mate up to convention delegates, he engages in a spirited contest wth young Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy, another advocate for the power of television in politics, with Kefauver eventually winning out. Had he chosen to run a third time, he would have been one of the favorites, and again would have clashed with Kennedy; he decides against it, though. Ironically, he dies in 1963—just as Kennedy does.

l l l

Ah, you ask—but what's actually on TV this week?

Remember

You Are There, the program that recounted historical events as if they were being covered on television? It started on radio in 1947, where it continued until 1950, and then moved to television in 1953, and ran until 1957, with Walter Cronkite as host. (There was also a brief revival as a Saturday morning show in 1971.) This week, Cronkite and crew cover the sinking of the Titanic (Sunday, 6:30 p.m., CBS). Now, as you know, I've always been fascinated by

related to the Titanic, so you'd expect me to bring this up, right? For good measure,

here's the link to the broadcast. Not quite as spectacular, perhaps, as

Kraft Television Theatre's

live production of A Night to Remember the following year, but it will certainly do.

Keeping with the nautical theme, Ed Sullivan and his guests salute Armed Forces Week onboard the USS Wisconsin on Toast of the Town (8:00 p.m., CBS); Ed's guests include balladeer Burl Ives (who's currently in the Tennessee Williams play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof *) with the Arizona Boys Choir; Carol Haney, a star in The Pajama Game; comedian Jack E. Leonard; singer June Valli; British comedian Richard Hearne; jugglers The Balladinis; and the Marines drill team, along with the band of the Wisconsin. Ed's competition is Promenade (7:30 p.m., NBC), a Max Liebman color review, hosted by Tyrone Power, with actresses Judy Holliday, Barbara Baxley, and Janet Blair; dancers Bambi Linn and Rod Alexander; singers Kay Starr and Jack Russell; and comedian Herb Shriner. Who do you give the edge to there?

*Ironically, the movie version, which Ives is also in, comes out in 1958, the same year as The Big Country, for which Burl wins a Best Supporting Actor Oscar; good year for him.

On Monday, Today (7:00 a.m., NBC) continues a series of reports on the upcoming British parlimentary elections, to be held on Thursday, with Edwin Newman in London. Edward R. Murrow is also in London for the elections, and he'll be presenting his report on See It Now (Tuesday, 10:30 p.m., CBS) The contenders are the current Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, and Labour leader (and former Prime Minister) Clement Attlee. You can tell the hightened interest in the elections here in the United States; Winston Churchill, America's favorite prime minister, had retired just the previous month, with his successor, Eden, calling a snap election to obtain a mandate. He gets it, as the Conservativs win a 60 seat majority; Eden himself will resign less than two years later following the Suez debacle. See how much history you can learn here?

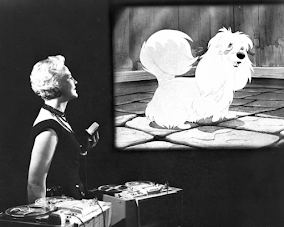

Walt Disney shows us what he does best on this week's

Disneyland (would that Disney would do that today), with a preview of the upcoming animated movie

Lady and the Tramp, feauting

◀Peggy Lee recording several of the voices she does for the movie. (Wednesday, 7:30 p,m., ABC). There's also a montage of cartoons featuring Pluto, celebrating his 24th year in movies. Meanwhile, on

Kraft Television Theatre (9:00 p.m., NBC), we get a look at the early pre-

Bewitched career of Dick York, who plays a rookie major league pitcher in "Million Dollar Rookie."

Burl Ives is back on TV Friday morning as Jack Paar's guest on The Morning Show (7:00 a.m., CBS), and again, he's described as a balladeer—the thesaurus must not have been at arm's length this week. (No mention of his acting career, though.) Today (7:00 a.m., NBC) presents a roundup of the British elections, as I imagine the other news programs will also. And in non-British politics, Margaret Truman guest hosts for Murrow on Person to Person (10:30 p.m., CBS); you can read more about that in my Monday piece.

l l l

And now, away we go with Gleason's million-dollar baby, Audrey Meadows, profiled by Kathy Pedell.

The Great One recently signed a contract with his sponsor and with CBS that amounts to $11,000,000, and for playing Ralph Kramden's long-suffering wife Alice, Audrey gets approximately one-eleventh of that—in other words, a cool million. It hasn't changed her that much, though; she bought a few good things ("I didn't feel too guilty when I bought my (first) mink stole"), and bought a new bedspread and some drapes for the three-room apartment that she used to share with her sister, Jayne, before Jayne married Steve Allen; Audrey says she's planning to stay there. But in case the temptation gets too strong, most of her cash was tied up by her lawyer brothers in investments; she admits she had more spending money when she was earning $75 a week.

|

| Who says they're not a couple of dolls? |

The two sisters, who have a close relationship in a business that's been known to drive wedges between celebrity siblings, have "Audrey" and "Jayne" dolls hitting the market this summer, they're also doing some recording and endorsing products. It's best not to take things for granted, Audrey says; "You may be in favor for three years—or 10—and then you may be out."

Getting the Gleason gig wasn't particularly straightforward; "[H]e had never seen me act, he had never heard of me, except from my manager. He didn’t know if I could act." And when her manager first suggested Audrey to Gleason, he vetoed her on the grounds that she was too pretty. "Alice has gotta be a mess," he said. Whereupon she brought in some photographers for a candid session. "My hair was uncombed, I wore my oldest clothes, a torn apron and no make-up. Then I stood in the kitchen and fried eggs. I looked awful. Even the eggs didn't look edible." When Gleason saw the pictures, and confirmed that it was Audrey, he said, "Any girl who would let herself be seen like that for a job deserves it."

Oh, and those lawyer brothers that Pedell mentioned at the outset? Well, as it turns out, brother Edward inserted a clause into that contract with Gleason providing that, should the Honeymooners episodes ever be rebroadcast, Audrey would receive a payment for them. Over time, she earned millions of dollars in residuals from the "Classic 39." She would be the only cast member to do so; only when the "lost" episodes were later released would anyone else receive them. Sometimes, it pays to have your brothers look after you.

l l l

It might only interest me—I mean, let's face it, that's what this blog is all about—but I enjoyed this brief articles showing us what goes into putting on the WCBS Late News, anchored by Ron Cochran.

It's a different era for news broadcating. There are no computers, no satellite hookups, no video cameras allowing for live remote broadcasts. The remote footage is comprised of film which has to be brought back to the station, developed, and edited before it can be shown. There's nothing fancy about the WCBS News Department, a cramped space located on the top floor of the Grand Central Station Annex, "an aged combination of sprawling, corridor-like rooms and tiny, closet-like offices" filled with teletype machines, cameras and projectors, typewriters, writers and newsmen. There's a constant rush of people back and forth, loud, chaotic. Cochran, who arrives at his office at 5:00 p.m., is the picture of calm, a man "who never raises his voice, or lowers his tie." He will be in the eye of the storm until he goes on the air.

It begins with a review of the early newspapers and wire services. At 6:30 p.m. there's a brief break for dinner, and then watching the 7:30 Douglas Edwards national news for a look at the news film. The top eight or ten stories are selected and given to the editor. The latest news film is screened; there's this description: "Cut out shots of mother crying over body of son, killed by car. Cut interview with cop; too funny for this tragedy." Not using the crying mother film shows a sensitivity that seems so alien to the "if it bleeds, it leads" culture, and I'd like to know what that cop interview was like.

The stories are divided up and work commences on the script. There are worries that the film needed for two stories won't be available until 10 p.m.; it arrives at 9:27, a triumph for everyone. The first run-through is at 10:05; the show runs 30 seconds too long. A story is cut, the teleprompter is edited, the cues in the script are changed. An additional story is added at 10:20, "just in case we run short." Cochran heads to the studio for makeup at 10:27. Camera cues are reviewed. Twenty minutes before airtime, a story requires updating; it's too late to change the teleprompter copy so Cochran will have to read the story from the script.

Finally, at 11 p.m., it's airtime. The theme runs, the announcer makes the intro, Cochran begins. Cues fly from the control room. Film is inserted into the broadcast. Cochran receives updates on timing. Fifteen minutes later, after the last story runs; "That's the news. Good night, all." It's 11:15 p.m, time for The Late Show.

Do you think Ted Baxter could have handled it all?

l l l

Last but not least, the shape of things to come, from the TV Teletype: "A long-time top-rated Los Angeles show, LAWRENCE WELK and his "champagne music," makes its network bow Sunday, July 2, on ABC." It remains in first-run, in one form or another, until 1982, and in reruns forever after. TV