Shows I’ve Watched: | Shows I've Added: |

The Man in Room 17 | One Step Beyond |

Maigret Public Eye Man of the World |

When last we visited this feature, you'll recall, I was recovering from a crisis of confidence in my ability to successfully pick TV shows to watch. There were consequences to be dealt with after the fact, though; one doesn't come through an ordeal like that without leaving some scar tissue.

My decision to temporarily shelve Alfred Hitchcock Presents left a four-night hole in our television viewing, and there was still some apprehension on my part about choosing the replacement. Rather than play it safe, I decided to go for broke; not one, but four shows would take Hitchcock's place: furthermore, all of them would be an hour in length, and to top it off, they were all British series from the early-to mid-1960s. I'm happy to report that these changes have made for a mostt satisfying result to the TV crisis, so let's take a look at this latest version of Britian's Fab Four.

|

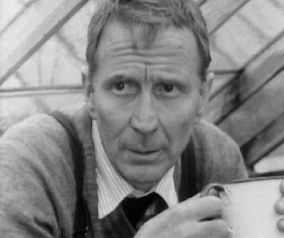

| Michael Aldrich (left) and Richard Vernon |

*Due to illness, Michael Aldrige is replaced in the second season by Denholm Elliot as the similarly-monogrammed Imlac Defraits; the reason for this obsession with initials will be explained in due course.

Oldenshaw and Dimmock undertake their assignments (provided they choose to accept them) with rapid-fire erudition and caustic wit, as well as total distain for their internal liaison, the bumptious and easily flustered Sir Geoffrey Norton (Willoughby Goddard). As one critic puts it, "Giving them orders would be an exercise in futility since they’d only ignore them anyway." When we come upon them, they're invariably engaged either in drinking tea, reading the newspaper, or playing the board game Go (the show's opening credits utilize the game's black and white stones as the motif). Each assignment is treated as an irritating intrusion, but they soon become wrapped up in the outcome—not so much because they want to defeat their adversary, but rather to prove they were right all along.

Some viewers might find the duo a little hard to take at times, with their air of condescension and superiority; Oldenshaw, in particular, can be acidly cynical about the government's involvement in these situations in the first place. They don't strike me that way, though; they're quirky, original characters, that you'll warm to, and their cases never fail to interest us—even when they don't interest them.

l l l

I consider myself fortunate to have found Rupert Davies's version of Maigret for Tuesday nights. Many actors have assumed the role of Georges Simenon's famous French police detective, including Michael Gambon and Rowan Atkinson, and while Gambon's excellent interpretation is probably the best-known, but for my money the definitive interpretation belongs to Davies, who played Maigret for four seasons between 1960 and 1963; among those who share my opinion is Simenon himself, who, upon meeting Davies for the first time, shouted, "At last, I have found the perfect Maigret!"

The exterior scenes in Maigret were filmed on location in Paris, lending an appropriate touch given that all of the actors are clearly British and make no attempt whatsoever to suggest any kind of French accents (a trait shared by all other British versions of the series*). That can be disconcerting at first, especially since French terms—monsieur and mademoiselle, oui, merci, patron (boss)—are sprinkled throughout the series. It doesn't take long, however, to get into the swing of things, thanks to well-written stories, an excellent supporting cast (Neville Jason and Victor Lucas as Maigret's colleagues, and Helen Shingler as his loving wife), and the performance of Davies himself.

*By contrast, if Maigret was adapted for American televsion, they'd simply relocate the series to New York or Los Angeles, change everyone's name, and lose all of the charm in the process.

As Maigret, Davies infuses the character with shrewdness and intuition, a world-weariness offset by wry good humor, and a blunt, direct style of questioning; he has a particular ability to put himself in place of the victim and see where it leads him, and a determination to get there. Unlike, say, Oldenshaw and Dimmock, he also projects a warmth and humanity unusual in most serious police dramas. He can be tough when necessary, and isn't above slapping around someone who deserves it, but it's so unexpected when it happens that it underscores Maigret's dedication to finding the truth. He's honest, loyal to his colleagues, and devoted to his wife. The cases are always interesting and the outcomes not always predictable, but the real pleasure is in watching Maigret solve them—and it is a real pleasure.

l l l

Not all private detectives are as suave as Peter Gunn, as tough as Mike Hammer, or as ready with a quip as Richard Diamond. Some of them are just hard workers, like Frank Marker, the title character of Public Eye, which aired on ABC Weekend TV and Thames Television from 1965 to 1975, and runs on Wednesday nights for me. As played by Alfred Burke, Marker is the prototypical private detective: a loner, cynical and world-weary, working out of a shabby, cramped office, taking on whatever cases come his way.

Public Eye makes clear that the business of being an "enquiry agent" is hardly glamorous; there are no car chases, no shootouts, no romances with beautiful, mysterious clients, and very few flying fists; his cases range from divorce actions to missing persons, what we're left with is Marker wearing out shoe leather, assuming various identities in order to ask lots of questions, and arriving at what is often an ambivalent conclusion to the case. In the case of the missing girl, nothing really changes at the end: Marker tracks her to an organized crime gang, where she has become a high-priced prostitute. She refuses his offer of help, thinking she has the leverage to take care of herself. She doesn't, of course, but she only finds this out too late, by which time Marker himself has been threatened off the case, forcing him to relocate from London to Birmingham. By the end of the third season, when Marker is betrayed by his client and winds up in prison after being convicted of receiving stolen property. The fourth season begins with him being released on parole, and having to accustom himself to life outside prison, his relationship with his landlady, and return to investigating.

Public Eye's long and successful run, and its status as a much-loved show of the past, can be attributed to the partnership of creator/writer Roger Marshall, and the performance of Burke. Burke is excellent in his portrayal of a three-dimensional, low-key hero who brings a sense of dignity to a quest for justice that often remains unfulfilled; while Marshall's stories are often downbeat and thought-provoking, frequently failing to provide neat and clean solutions to scenarios that don't wrap themselves up nicely at the end of the hour. Working together, the two give us a look at the moody, atmospheric world of England in the 1960s and 1970s, a world where the truth is elusive and there are no easy answers

l l l

Speaking as we were of Peter Gunn, two of the men who made that series so memorable—Craig Stevens and Henry Mancini—reunite for Man of the World, the 1962-63 ITC drama that provides a perfect conclusion to this quartet of programs. Stevens is charming, smooth, and in control—in short, everything you'd expect him to be—as Michael Strait, a world-famous American photojournalist who travels around the world on his boat, covering stories big and small, accompanied by his lovely and resourceful assistant Maggie MacFarland (Tracy Reed), who's become quite used to her boss's duties bringing him out from behind the camera lens. Throw in Mancini's elegant opening theme, and you're all set for an hour of globetrotting glamour and adventure.

You wouldn't necessarily think that beng a photographer would be so dramatic, not to mention dangerous (it's a lot safer operating a studio in a busy storefront), but Strait obviously thrives on it, often taking on assignments for intelligence agencies in locales such as West Berlin, Vietnam, and Cuba, using his photographic skills to provide cover for obtaining information on various threats to the free world. And when he's not involved in high-stakes geopolitics, he's dealing with millionaire clients, mysterious heiresses, and ruthless killers. I guess it does beat working for a portrait studio. One early episode, "The Sentimental Agent," serves as a backdoor pilot for the later series of the same name, starring Carlos Thompson as an import-export agent who, for the right prices, is willing to undertake assignments as far removed from his business as, well, photography is for Strait. In this case, he's recruited by Maggie to rescue Strait from a Cuban prison after Michael's been caught taking pictures of the wrong person. Does he succeed? C'mon, it's only the sixth episode; what do you think?

If you think Man of the World sounds as if it bears a passing resemblance to shows like The Saint and The Baron, you're absolutely correct. It also comes from an era when Lew Grade, the head of ITC, was convinced that casting an American star was the way to crack the U.S. market, a la The Avengers and The Saint. It didn't work, which is why this series might not be familiar to more of you. And while it doesn't have the dash and success that the latter two series had, it's certainly a pleasant way to spend an hour. Best of all, it won't leave you second-guessing your viewing choices—like some series we could name. TV