by Stephen Taylor

We were not an

Ironside household as I grew up. I never saw a single episode of the show as a child, and grew up knowing only that it involved a cop in a wheelchair; that was the extent of both my knowledge and my interest in the show. I’m much older now, and I have time to watch old television shows, and I thought I’d give

Ironside a try. I’ve always enjoyed Raymond Burr, and thought the show might be fun to watch. I’ve watched the first three seasons, and thought I’d offer a few comments.

The premise is this: Robert T. Ironside (Raymond Burr) is the Chief of Detectives for the San Francisco Police Department. He survives an attempt on his life, but suffers an injury which leaves him a paraplegic. Forced to retire, he returns to the SAPD as a consultant; he forms a special unit comprised of Detective Sergeant Ed Brown (Don Galloway), Officer Eve Whitfield (Barbara Anderson) and assistant Mark Sanger (Don Mitchell). He reports to Police Commissioner Dennis Randall (Gene Lyons). The special unit handles almost every sort of crime, from con artists to car thieves to murder to property theft to security for dignitaries and more. Sometimes they’re directed by the Commissioner to handle certain crimes, but they mostly spring into action unbidden. It’s a standard police drama centered around Burr, except that he’s in a wheelchair.

The two-hour pilot aired in March of 1967. It was pretty good; it introduced Ironside and his team to the audience, and explained how Ironside came to be in that wheelchair. There is a lengthy list of suspects, as Ironside was not popular with quite a few people. The ending was fairly suspenseful; the murderer was not who you might think it was, and the pilot made a basic attempt to show how Ironside assembled his team. Sgt Brown and Officer Whitfield he wanted because “they’re good cops!” Mark Sanger was a different story. Ironside had already sent Sanger to jail twice. Hearing that Sanger was downstairs in booking and making threats about “getting” the Chief, Ironside had Mark brought to his office, where he offered Sanger a proposition: come to work for him or go back to jail. Push the wheelchair, assist Ironside in

getting around, perform odd jobs, other duties as assigned. All for the princely sum of $20 a week. Sanger accepts, but he’s an angry black man. Very angry. Angry, but not stupid, and knowing that he’s entered an important fork in his road, he accepts. His hiring set up some of the only conflict between characters the show ever had.

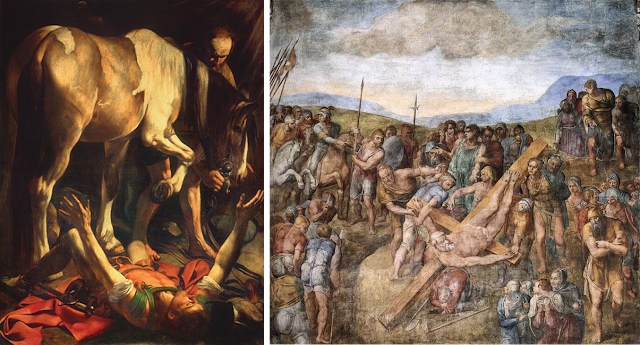

Raymond Burr was an excellent actor. He’d been a supporting player in movies since the Forties, and could play a variety of parts. He committed a murder in

Rear Window, and starred as a psychopathic gangster in a movie called

Raw Deal* in 1948. He already had a lengthy track record on television; he’d starred in

Perry Mason as the titular character in the long-running series about a defense attorney. America knew Raymond Burr, and they liked him. Never a father figure, he was the gruff but avuncular uncle who always knows how to be stern with an adult but kind to a child; understanding always, but insistent on a moral code based on honesty and integrity. The part of Chief Ironside called for this character, and it fit Raymond Burr to a T; he’d been playing a variation on that character for the last 10 years. For his part, Chief Ironside

had been a cop for at least twenty years. It’s mentioned that he’d been in the Navy, presumably in WW II. He’d risen through the ranks to Chief of Detectives, where he stayed until the attempted murder. Even as a consultant he’s still called “Chief” by his subordinates and others. There are exceptions; those exceptions being his aunt; who calls him Robert, and Commissioner Randall, who, along with all his old flames, and there were many old flames, calls him Bob.

He’s gruff and something of a tyrant, yet capable of acts of astonishing kindness and generosity. He takes no guff from anyone. He demands respect and gets it; even professional criminals respect him, as they know he’s fair and will never give them a raw deal or go back on his word. He has a keen sense for when something’s not quite right, a sharp eye for detail, and a knack for interrogation. He inspires an almost slavish loyalty from his team, and sometimes abuses that loyalty; he also has a short temper and isn’t above raising his voice if something displeases him. The show was centered around Chief Ironside, and it’s fair to say that Raymond Burr carried the show. Burr, in this part being confined to a wheelchair, has to rely on his face to convey mood and emotion, and he’s gifted in doing so. He could convey anger, happiness, deep suspicion, exasperation and many other emotions with his expressions or the way he held his jaw. He’s quite good.

Sergeant Brown (Don Galloway) is a detective sergeant who landed on the team simply because Ironside approved of his work as a detective. Although portrayed as a bit of a bumbler in the early episodes, he soon demonstrates that he is fast on his feet, good with interrogation and even better at anticipating the Chief's next request/demand. He seems to have been born suspicious; his eyes squint when he smells a rat, and they squint a lot. He doesn’t seem to have any sort of personal life. And Don Galloway is woefully miscast in this part. I don’t know much about Galloway. I don’t remember seeing him either before or after

Ironside. He makes no strong impression. Brown’s a detective sergeant, meaning that he’s a veteran who’s seen every side of the human condition, including a great many things civilians can only imagine. There are many ways to die, and he’s seen all of them. Yet none of it registers on his face. There are no lines or wrinkles; nothing to indicate that his experiences have changed him. He’s just an anonymous guy wearing a suit who happens to carry a badge. He has no gravitas. No bearing. He’s simply not believable. Galloway reminds me of Dick Sargent, not a detective in a large city. He’s simply too clean-cut to believably play the part. He’s not objectionable, and he does sort of grow on the viewer, but he never really makes an impression. And he’s not given a lot to do.

Only one episode, “Girl in the Night” from the first season, really centers on Brown; he meets a troubled nightclub singer (Susan St. James) and becomes attracted to her. Sparks should have flown, but they didn’t. He just isn’t believable as the sort of guy who might meet a

nightclub singer and have a brief fling. Susan St. James lit up the room, but it was as though she was talking to a wall for all the good it did her. His casting was a loss to the series. It will be interesting to see if he’s given more to do in later seasons, but Brown was horribly miscast.

Journeyman director Ralph Senesky directed “Girl In The Night”. On his website**, Senesky

discusses the production of this episode, as well as his general opinion of Universal Television,

which wasn’t favorable. He did think that “Girl In the Night” turned out well, however.

Oh, my. I spoke too soon. I wrote the above after watching all but the last episode of the

third season. After an entire season of indifferent writing and acting, would the last episode be

the one to break the pattern? Yes. A very strong yes. Don Galloway, please forgive me.

Don Galloway finally gets a chance to shine in an episode at the end of the third season; “Tom

Dayton Is Loose Among Us” shows us that despite being miscast, Galloway could act, and the

episode answers some questions the audience has about Sgt. Ed Brown. Bill Bixby plays a

sociopath named Tom Dayton, with William Smithers being cast as defense attorney Ross

Farley. Dayton tends to react violently to women in positions of authority. During one such act

of violence, he causes the death of Brown’s fiancée. Finally, we get some backstory.

Finally.

Told in flashback, Brown, a rookie patrolman at this point, becomes obsessed with catching

Dayton, and gets in the way of Ironside’s investigation into her death. Ironside isn’t happy, and

he lets Brown know it, but he also senses the makings of a good cop in Ed Brown, and invites

him to join the investigation. Brown comports himself well, and Ironside makes a mental note

for the future. But it isn’t over. Not yet.

Seven years later, Dayton is paroled. Brown, a Detective

Sergeant by this time, is convinced that Payton will strike again. His old obsession with Payton

returns; he’s angry and in danger of losing his objectivity regarding Payton; it gets to the point

that Ironside has to tell Brown to stand down. And Payton does strike again. Ironside, to show

his trust in Sergeant Brown, allows him to conduct the initial interrogation after Payton

surrenders in the company of attorney Farley. Bill Bixby puts on an acting clinic in the entire

episode but especially this scene, proving once again what a superb actor he really was; this is

a juicy part and he makes the best of it. But Don Galloway, bless his heart, reaches deep within

himself and finds acting talent he probably didn’t even know he had; he matches Bixby stroke

for stroke during the interrogation. Sgt Brown begins by trying to build some rapport with

Dayton, and he’s successful. He then pushes, pokes, prods and goads Dayton to answer, as

one man to another, some questions about the most recent assault he’s committed. And as

Brown continues to push, Dayton begins to lose control. Brown pushes even more, and Dayton

cracks wide open.

Defense attorney Farley can’t do anything but give himself a facepalm; he’s

never seen an interrogation go off the rails like this, and it gets worse. After Brown finally goads

him into losing his last vestige of self-restraint, Dayton concludes by giving a full confession;

he’s proud of himself, and with rapport established, is convinced that Sgt. Brown surely

understands why he assaults the women who show him disrespect. And, while conducting the

interrogation, an entire range of emotion plays across Brown’s face; he’s alternately amused,

understanding, angry, misbelieving and repulsed, all within the span of just a few minutes. It’s an

excellent scene, with tour de force acting by Bixby forcing Galloway to up his game; he doesn’t

want Bixby to show him up, and that certainly doesn’t happen here. More of this from Don

Galloway, please. Give us more.

Barbara Anderson portrayed Officer Eve Whitfield. The Chief selected her at the same time he selected Sgt. Brown, because “they’re both good cops”. Barbara Anderson certainly wasn’t miscast. She could act (Lenore Karidian, call your office….) and she’s given a backstory. Eve was a young socialite with a strong sense that there might be more to life than fashion shows. The episode “Reprise” had a badly injured Whitfield recalling how she met each of her teammates. Ironside, who had an absolute gift for sensing human potential, sized her up as a potential police officer, but he had to reel her in, and the early scenes between the Chief and the civilian Whitfield were excellent. She’s a snappy dresser (Barbara Anderson was beautiful) and does a lot of undercover work on the show.

She’s also unafraid of danger. While leaving a movie theater, she quite literally walks into the middle of a jewelry store robbery, and comports herself well in the ensuing gunfight. This was one of the best episodes of the first season; it’s called “All In a Day’s Work”, and it’s good. Eve shoots down one of the robbers, and is horrified to find that she’s just killed a teenager. She becomes afraid of her pistol, “forgetting” to put the pistol in her purse when she leaves the office and performing abysmally at the gun range. Ironside grows exasperated with her and essentially tells her to put on her big girl pants and be a cop. Which she does. The others were horrified at his attitude, but his little lecture is just what she needed. The ending is a little pat, as almost all the endings were, but this episode was a cut above the rest, due mainly to her acting and the writing by Ed McBain (Evan Hunter). I had no idea that Evan Hunter had done any writing for TV, but he did indeed, especially in his salad days in the 50’s and 60’s. You can tell it in this episode; the writing is a little sharper and the characterizations a little more vivid. And it includes one of the best scenes in the series.

Ironside is talking to the mother of the dead boy; she’s played by Jeanette Nolan, one of the best character actresses I’ve ever seen. Raymond Burr was one of those actors who could draw a better performance out of another actor simply by being in the same scene, but Nolan needed little prodding. The scene lasts about three minutes, but it’s very emotional. She doesn’t want to help Ironside find the Fagin who was running the robbery ring, and Ironside has to convince her otherwise. A lot of emotion and feelings rubbed raw here, and the final moment when Nolan relents and gives Ironside the information he needs is just excellent. It’s always a joy to watch two fine actors work together, and this is a fine example of just how well Raymond Burr could act, especially with actors who were his equal.

Don Mitchell played Mark Sanger. Mark Sanger had to be easy to write for, as Sanger was

an interesting character. Mark Sanger grew up on the mean streets of the city, probably in

Fillmore. It was a challenging life for a boy with no father and Mark began to drift into crime. As

an adult, he’d been sent to jail multiple times by Chief Ironside, and Mark didn’t appreciate that

one bit. He was angry, not just at Ironside, but at everything. He was an angry black man, and

meat for multiple scripts which explored his upbringing and his relationship with Ironside. He

respected Ironside, and ultimately came to care for him very much. In return, Chief Ironside was

proud enough of Mark that he paid for Mark’s education, which ultimately led to his becoming a

lawyer.

But in the beginning there were fireworks. In “Memory Of An Ice Cream Stick” from the first

season, Mark goes to visit an adult figure from his childhood named Sam Noble; Noble has just

been released from prison. Mark has pleasant childhood memories of the ex-con; Noble treated

Mark decently and gave him a sort of father figure to look up to. Ironside warns him against

being involved with Noble, as he suspects Noble is involved in a gangland murder. Mark

declines Ironside’s request, and forcefully explains to Chief Ironside that he doesn’t need or

want his advice, that he is a grown man, and that the Chief simply does not understand how

Mark grew up or the role that Sam Noble played in Mark’s life. He is tired of the Chief’s advice

and admonishments in general, as well as his patronizing attitude. The Chief is taken aback,

and, for both the first and last time in the first three seasons, apologizes. He takes Mark’s

request to heart, and Mark learns a valuable lesson about childhood memories when he finds

that Noble is indeed involved in the murder, and that he’s not at all the man Mark remembers.

As the series progresses Mark begins to loosen up; he works well with the other members of the

team, and begins doing more and more police work.

My overall impression of the series is that it’s a routine police procedural with some nice

touches. The writing and direction was routine, and the acting routine as well. In his discussion

of the two episodes he helmed for

Ironside, director Ralph Senensky refers to Universal as a

factory; he stated further that, and I’m paraphrasing, that simply driving through the Universal

gate seemed to drain all the creativity out of him. It’s tempting to say that

Ironside was routine,

and to simply leave it at that. Except that that’s not really fair to Universal Television. NBC,

Universal and Harbour Productions signed a contract guaranteeing NBC 26 episodes of a crime

drama; each episode was to be about 52 minutes long, and each episode was budgeted at

between $150,000 and $200,000 apiece, and each episode had a shooting schedule of either

six or seven days. It was right to say that Universal was a factory; they really were making a

product, and their customer was NBC. Consistent excellence simply wasn’t possible under

these conditions. And quite a bit depended on the mix of producers, writers and directors.

Some dramas, such as

The Fugitive, simply had a better mix of the three and were able to turn

out consistently better episodes.

Ironside did not. As a result of all these factors, there were

many episodes of

Ironside that were simply routine at best and nearly unwatchable at worst.

This was never the intent, but it’s just how it played out.

Having said all this, sometimes the factory turned out some excellent television. And the

best was an episode called “Price Tag: Death”. It starred Ralph Meeker as a homeless former

cop, and

◀ Clu Gulager as a petty thief who lives in the bottle. During a burglary, the thief

accidentally kills a homeless man, who was a friend of the fallen cop. Meeker asks Ironside for

help. Jack Brody, the thief played by Gulager, is a pathetic figure. He’s a boozer. He’s lost his

wife and family. He sits and smokes and drinks all day. He writes bad checks to generate an

income; he’s discovered that if you buy some groceries at a supermarket, they’ll let you write the

check for some amount over the purchase amount. He dumps the groceries and lives on these

small sums of cash. He’s a complete loser. He goes to see his ex-wife; she wants nothing to do

with him and doesn’t want him near their children. He picks up a woman at a bar and takes her

home, only to wake up the next day to find that she’s cleaned out his wallet; she even returns

later in the day and steals the machine he stole during the disastrous burglary, which he uses to

make the checks he cashes, meaning he no longer has an income. He wrecks his car. His

pitiful little life is falling apart, and he’s almost relieved to be shot to death at the end of the

episode.

What to say? Clu Gulager’s acting is outstanding. Gulager was one of those actors who

was never going to carry a show, and he didn’t do character roles. He spent nearly his entire

career doing Guest Star roles such as this one. He was one of those rare actors that

screenwriters live for; give him some good lines and he runs away with them. His Jack Brody is

vivid; the cold sweat of desperation oozes from every pore on his body. He’s trapped in this

cycle of petty crime, and he doesn’t know how to escape. He’s simply a bystander who watches

as his life, which wasn’t much to start with, degrades with increasing speed. Clu Gulager plays

this role very, very well, and is completely believable as the alcoholic loser who isn’t even a very

good thief. Kudos also to director Richard Colla and writers Collier Young and Robert Earll, who

wrote the lines which Clu Gulager used so effectively to define Jack Brody. This is the best

episode yet in the first three seasons, and perhaps one of the best episodes of series television

I’ve ever seen.

Ironside is worth watching. It’s not great television, but it is entertaining. It doesn’t enjoy the

same iconic status in our culture as other shows of the period, such as

Mannix and

Star Trek,

but it succeeds on its own merits as simple entertainment and a pleasant way to spend an hour.

This set of episodes was packaged by Shout! Factory; for whatever reason they only released

the first four seasons. The second set has been released by an Australian company called Via

Vision, and it’s proving difficult to find; it goes in and out of stock at all American retailers. If you

enjoy vintage television from a different time and place, you’ll enjoy

Ironside.

*

Raw Deal is a gem. It’s one of the finest film noirs ever made. Directed by Anthony Mann, with

cinematography by the legendary John Alton, it really gives Raymond Burr a chance to shine as

the sadistic gangster Rick Coyle. While not the main character, Burr chews the scenery, and

plays evil very convincingly; he has an epic death scene which can only be envied by other

actors. ClassicFlix has

re-released their restoration of

Raw Deal; their restoration is pristine.

This movie is an excellent introduction to the world of noir, and Raymond Burr is a huge asset to

a movie which also stars Dennis O’Keefe, Marsha Hunt and Claire Trevor. John Ireland plays

Fantail, Coyle's psychopathic assistant. Highly recommended. This movie is without flaw.

** Ralph Senensky has made an invaluable contribution to television history with his

remarkable website “Ralph’s Cinema Trek”. Senensky, who’s still with us at 99, was a

journeyman director who worked in television from the Fifties into the Eighties; he directed

episodes of a great many iconic television shows, including

Ironside, Mannix, The FBI, The

Fugitive and many others. He’ll still be known in 100 years, after all the other shows are

forgotten, for directing seven episodes of

Star Trek. Senensky was a competent and respected

director who could solve problems on the fly, knew how to improvise, and most importantly, he

knew how to put a show in the can on time and on budget. His website is packed with his

memories of nearly every episode he directed; he illustrates his stories with embedded clips

from each show, as well as imagery of scripts and other documents used to illustrate his

memories. His stories are priceless, as they provide a up-close look into television production of

that time. My favorite article talks about how he was fired from “The Tholian Web”. Be prepared

to spend hours reading the articles. He helmed two episodes of

Ironside, “Girl in the Night” and

“Return of the Hero”. He never liked working for Universal; he makes his reasons abundantly

clear in the article detailing the productions of these two episodes He describes Raymond Burr

as “aloof”; he also describes some of the troubles Burr was beginning to have with Universal.

Good, good stuff. His website is at

senensky.com. Give it a look-see.

TV