l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

When was the last time we had a positive—I mean really positive—review from ol' Cleve? Well, get ready, because ABC's new variety series This Is Tom Jones is the real thing.

Displaying "one of the most infections grins ever to cross the Atlantic," Jones captivates from the very beginning of the very first show, a program "so sumptuously mounted and inventively shot that, compared to most American variety shows, it broke new ground in not only backgrounds, but in variety too." The camera in production numbers "literally seemed to dart in and out, giving us so many peek-a-boos that at times it almost seemed sublminal." And while Jones occasionally looked "like a sick fish" when he leaned on a rock number, he also displayed a smoothness with his guests and (all-girl) staff that "seemed as charming as Dean Martin." The guests were also, for the most part, very good, particularly "a young French singer, Mireille Mathieu. The only way to stop her from stealing a show would be to arrest her before the show starts." Now,

we've read about her in TV Guide before, so we shouldn't be surprised by Cleve's captivation with her, nor that he refers to a later show featuring "a singer from the first show who was evidently out on parole. Can you guess who she was? Well, we'll give you a hint—her initials are M.M."

Amory had wondered if this first show would be the exceptioin rather than the rule, if they would "still use all this high-test or go back to regular gas" but he needn't have worried; "This Is Tom Jones was high-test all the way," beginning with a performance of "Help Yourself" on a stage "with so much going on that it was just like watching a three-ring circus," before deftly and almost imperceptibly segueing into a soft and memorable rendition of "Green, Green Grass of Home." The show included two particularly memorable guest appearances from relative newcomers: a Welsh singer named Mary Hopkin and a comedian named Richard Pryor. Not bad. Yes, there's more than Mireille to this show, and as long as Tom Jones brings it, he'll continue his "tremendous start."

l l l

One of the tragedies of American education over the decades is the virtual disappearance of music appreciation courses. Numerous reasons have been given for this, reasons that rapidly become political and which we don't need to discuss here. But I have to wonder how much of a role was played by the cancellation of programs like

Captain Kangaroo. The pictures on the left shows highlights from "Jazz Week," a special week beginning April 7, in which the Captain (Bob Keeshan) and Billy Taylor, the American jazz pianist, composer, and broadcaster (he's currently porgram director of New York's WLIB radio) are going to present a history of jazz, featuring special guest artists.

On the top left, we see the African musical group Babatunde Olatunji and Company; tenor saxophonist George Coleman is on bottom left; on on bottom right is ragtime/blues pianist Willie "the Lion" Smith, along with Keeshan and Taylor. Other musicians include Wilbur de Paris' Zeba, talking about improvisations, solos, and counterpoint; the Eddie Daniels Quintet, demonstrating swing and bop; and Taylor's own quintet, performing with the Eric Gales group to demonstrate the influence of jazz on rock. "Might make for some swinging kids," the article concludes.

I was critical, or at least ambivalent, when

I wrote about the generation that grew up watching

Captain Kangaroo, but at the same time I retain a great affection for the program. My love of reading started with the Captain (as it did for my wife), and it, along with Bugs Bunny cartoons, provided me with an introduction to music appreciation. Programs such as

Sesame Street, for all the good they may do, seldom offer such long-form exploration of single topics like music; local children's shows, especially in large cities, often had guests from that city's performaning arts groups. And so, again, I wonder how much the disappearance of shows like these (and Leonard Bernstein's

Young People's Concerts) have had to do with the lack of music appreciation.

The appreciation of the classics, including jazz and its related genres, may seem like a small part of a child's education, but it helps to create a well-rounded, civilized young person growing into adulthood, and I think we can certainly use more of that in today's culture.

l l l

I'm aware that there are a lot of things that were amazing back in the day, but hardly attract any attention now; the fact that I was amazed by these things just reminds me of how old I am. For instance, it's hard to explain what a big deal the Houston Astrodome was when it was built. A domed stadium! Indoor football and baseball! Even a basketball game, with a record crowd! It seemed as if there was nothing the Astrodome couldn't do, and we get an example of this on

Saturday's

Wide World of Sports, with coverage of last week's Grand Prix Midget Auto Racing Championship for dirt track cars (5:00 p.m. PT, ABC). The idea of indoor auto racing—well, that just about takes the cake. And if you think dirt track rasing isn't the real thing, the drivers are Bobby Unser, Mario Andretti, A.J. Foyt, and other stars from Indycar racing. You can see highlights of that race weekend

here.

Sunday's

Public Broadcasting Laboratory (8:00 p.m., NET) presents a cinema-verite profile of Johnny Cash, "an authentic folk hero, self-made from the crucible of the American experience during the Depression." The producers explain that Cash's reticence required them to rely on observation; there is no narration, and besides excerpts of Cash performing, we see him visiting his family, returning to an Arkansas shack in which he once lived, and a chance meeting between Cash and Bob Dylan. You can see this documentary

on YouTube.

On Monday, a two-hour ABC News Special, "Three Young Americans In Search of Survival" (9:00 p.m.) tells the story of these three young people, working to better the world they live in. One is an environmentalist, the second works with blacks in the ghetto, and the third is fighting water pollution. One could do a similar documentary today, using the same title, to tell of three young people struggling with the prospect of finding work in the rust belt, poverty and illiteracy in the Applechians, and searching for meaning to life in a world rapidly stripping away all cultural norms; that's the kind of thing I think of when someone talks about searching for survival. But we deal here with what we're given; Paul Newman narrates the special. By the way, it's interesting how the definition of "young people" has changed over the years; these three are 26, 32, and 30, respectively; Greta Thunberg would probably accuse them of being part of the establishment.

Tuesday's Red Skelton Hour (8:30 p.m., CBS) features guest star Merv Griffin spoofing his own show, interviewing three of Red's most famous characters: Cauliflower McPugg, Boliver Shagnasty, and Willy Lump-Lump; Merv also sings his back-in-the-day hit, "I've Got a Loverly Bunch of Coconuts." I love hearkening back to those days when talk show hosts had to have some actual talent. After an interlude with The Doris Day Show, CBS continues with an episode of 60 Minutes with Mike Wallace and Harry Reasoner (10:00 p.m.), which, as the listing reminds us, was then a bimonthly show. It's easy to forget that it wasn't until 1971 that 60 Minutes first aired on Sunday nights, and it was 1973 before it settled there for good.

|

| Andy with Donovan. Dig the groovy shirt! |

Speaking of Sunday, I always think of Glen Campbell's show as beng on Sunday, probably because he started out as the summer replacement for the Smothers Brothers, but here he is on

Wednesday, leading off an interesting night of variety shows. (8:00 p.m., CBS) Glen's guests tonight are Jim Nabors and Bobbie Gentry, and there's a note at the end that Cleveland Amory will be reviewing the series next week. That's followed by a pair of specials on NBC: first, Bob Hope presents "an hour of comedy and song" with guests Jimmy Durante, Cyd Charisse, Ray Charles, and Nancy Sinatra. (9:00 p.m.) After that Andy Williams hosts a flower-power "Love Concert" (even the stage is covered with flowers) with Jose Feliciano, Donovan, the aforementioned Smothers Brothers, and the Ike and Tina Turner Soul Review. (10:00 p.m.) Hang on a minute while I get my Nehur jacket and beads.

I've mentioned this before, I'm sure, but I'm counting on most of you having forgotten about it. (At least I'm honest!) As you're reading this, we're in the midst of March Madness, with everyone and his great-aunt hosting some kind of bracket to make the NCAA basketball tournament worth watching. The tournament wasn't always such a big deal, though; on Saturday afternoon, NBC broadcast an "Elite Eight" doubleheader (it was just called the quarterfinals back then) featuring two of the four games being played—the Eastern and Central time zones got the East and Mideast finals, while the Mountain and Pacific time zones got the Midwest and West finals. Now, on Thursday, the winners of those four games meet in the Final Four in Louisville, and once again the game—yes, you only got to see one of the games—depends on where you live. The East and Central get the first game, the Mountain and Pacific get the second, which in this issue means Drake vs. defending champion UCLA. (7:30 p.m.) Dragnet and The Dean Martin Show follow the game. Once again, we're reminded how times have changed.

NBC finishes the week with a couple of interesting programs on Friday; first, The Name of the Game (8:30 p.m.) showcases a terrific lineup of British guest stars: Honor Blackman, Maurice Evans, Brian Bedford, and Murray Matheson among others. The story takes Glenn Howard (Gene Barry) to London to defend the company against a libel case being prosecuted by a crooked counselor (Blackman). Then, it's a Bell Telephone Hour special on the great Hollywood movies of David O. Selznick. Henry Fonda narrates; the special includes, for the first time on television, the burning of Atlanta scene from Gone with the Wind.

l l l

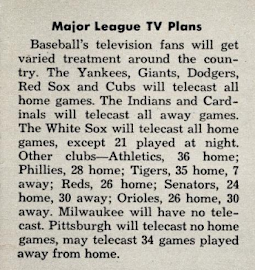

Finally, the start of baseball season is just around the corner, and one of the most interesting former baseball players around is Joe Garagiola, one of the hosts on NBC's Today. Now, I'll admit that I've never been a particular fan of Garagiola—I always thought his mouth was a little too small for the number of words trying to get out, and I didn't find his humor that funny—but I'll also admit when I'm wrong, and in this case I've come away from Stanley Frank's article much more impressed than before.

Joe's been on

Today for the last year and a half, and during that time the show's ratings have risen to an all-time high. After an eight-year career, spent mostly as a backup catcher for the St. Louis Cardinals, he segued into broadcasting. He'd already become a popular after-dinner speaker because of his folksy, self-deprecating sense of humor, and an appearance with Jack Paar eventually led to his role on

Today. You might have expected him to serve as the token jock on the show, reading the scores and narrating the highlights from last night's games, but you'd be wrong. "Joe has a marvelous quality of cutting through the malarkey from pundits and pretentious writers by asking the questions viewers want to hear," producer Al Morgan says, explanating why he expanded Garagiola's role beyond sports. "He’s a very bright. guy who does his homework. Besides, I could trust his taste and judgment implicitly." Adds

Today host Hugh Downs, "I have a tendency to be stuffy and pedantic. Joe's direct, down-to-earth approach counterbalances that element in me and gives the show the vigor that keeps it moving. He knows how to bring out the truest in a guest. That's his great forte."

Garagiola shares his experiences interviewing people outside the sports beat. Of poet Marianne Moore, whom Garagiola had never heard of prior to researching her for the interview, he said, "She bowled me over with her charm. She had a violent crush on the old Brooklyn Dodgers and reminisced about them for 10 minutes. I finally got her to talk about poetry and I was given a better appreciation of it than I'd ever learned in school." During one interview, he contfronted cultural historian Lewis Mumford, who deplored living conditions in the cities and suburbs, but admitted that although he had an apartment in New York, he went to his house in the country when life in the city got to be too much. "Few people can afford to maintain two homes,” Garagiola replied. "People like you should be working on solutions for urban problems instead of writing off the whole thing as a hopeless mess." And when Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), complaining about discrimination in America, said, "I live here, but it's not really my country," Garagiola told him during a commercial break that "If you want to move, OK. But if you want to live here, you'd better go out there and square yourself with people who are sympathetic to your cause." After they returned, Alcindor said he hadn't really meant to repudiate his citizenship.

Garagiola puts in 12-hour days preparing for interviews. When talking to authors, "Downs admits he skims through 20 percent of a book; but Joe, lacking his colleague’s background, reads it all the way through." The foyer of his house is lined with 20-foot shelves of books; Garagiola has read most of them. He enjoys Today, but admits to an idea he toys with: "I'd like to do a Saturday morning show talking to two kids without patronizing or putting them down and see the world through their eyes." He also recalls talking with members of the hippie compound at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. "When I asked what their beef was against society, they gave me a lot of tired cliches and ended every sentence with, 'You know what | mean?' Well, I didn’t know what they meant and they couldn't express it, clearly and simply. Maybe a guy like me could help them bridge the communications gap." That sounds like a home run idea to me; it's a pity people can't try something like that today.

l l l

MST3k alert: The Deadly Mantis (1957) "A paleontologist suspects that a gigantic prehistoric mantis has returned to life. Craig Stevens, Alix Talton, William Hopper." (Saturday, 2:30 p.m., KHSL)

You would think that a movie starring a couple of superstar detectives like Peter Gunn and Paul Drake would be better than this, right? But it's still good fun. TV