We're giong to meander a bit this week, flitting from one topic to another with something less than reckless abandon; maybe there's a thread that connects everything—we'll just have to wait until the end and see what we come up with.

But we're going to start by talking about creativity. It seems as if we don't see much creativity in television anymore. I don't mean that there aren't creative programs out there, series that stretch the limits of their genres to places that weren't previously considered. No, I'm talking about the genres themselves; in my memory, I can only think of three really new trends, and even then not all of them are all that "new": the dramedy, a show that's neither fish nor fowl, neither drama nor sitcom; the concept of "story arcs," working in tandem with the increasing serialization of dramatic television; and the miniseries, which functioned as an expansion of a TV-movie to fill several nights, either weekly or consecutively. (There may be more that I've overlooked—in fact, I'd bet on it, so feel free to enlighten me in the comments.*)

*I'm not including "reality" shows in the conversation, other than as an experimental format (An American Family, for example. There's nothing real about today's reality shows.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

It's too bad, because I think we miss out on programs that could have some real potential. Take, for instance, the rerun showing of Annie, the Women in the Life of a Man (Wednesday, 9:00 p.m. PT, CBS), a collection of 14 comedic, dramatic, and musical vignettes starring Oscar and Tony winner Anne Bancroft and featuring "a star-studded assemblage of gentlemen friends." Each story presents Bancroft in a particular archetype: the "blushing bride," with Dick Shawn as the groom and John McGiver as the father; the "middle-aged neurotic," with Lee J. Cobb as her psychiatrist; the innocent show-biz hopeful, auditioned by David Susskind; and so on. She dances to "Change Partners" with Arthur Murray, is serenaded by Robert Merrill in "Stay," and thinks of her son (Dick Smothers) away at war in "Maman." As the "harried wife," Bancroft dramatizes three poems by Judith Viorst; "The Night Was Made for Love" is a production number with dancers.

The hour showcases Bancroft's considerable talents, of course, along with a terrific lineup of guests, but what intrigues is that it doesn't fit easily into any conventional format; it's obviously not a one-woman show; the singing and dancing sequences mean it's not a collection of one-act plays; it has a consistent theme—the various roles played by a woman—and a singular star, but other than that it's something new, something different. It most closely resembles a variety special, but even there, with its set dramatic pieces, it's not your typical one. TV Guide's Scott MacDonough calls it "a sparkling parcel of pure pleasure," and includes praise for "the brisk contributions" by the show's writers, including one Mel Brooks, who happens to be Bancroft's husband.

There are plenty of musical-comedy actresses (and actors too, for that matter) who could do something like this today, even though they might not be as talented as Anne Bancroft. Perhaps someone has done something like this recently, or at least in the last few years; I don't know. But in a day when television presented a greater variety of programming that it does today, Annie, the Women in the Life of a Man, was something out of the ordinary, and I think we could do with a bit of that today; at the very least, it beats reboots. Just because Cop Rock was a bomb doesn't mean you don't try again.

Here's a clip of Bancroft performing the Judith Viorst poems, and another of her with Lee J. Cobb. (Is that what David Letterman was thinking of?) After this show, she'd add an Emmy to her Oscar and Tony. Not bad.

l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era. Next we have Cleveland Amory's take on a program that was considered one of the most creative children's shows of its time, Sesame Street. At this point in the conversation, the Street has only been open for three months, but Cleve is already comfortable in asserting that Sesame Street "is far and away the greatest children's program that has ever been on the air."

Kukla began on Chicago television in 1947 before moving to NBC the following year (airing daily at 6:00 p.m. Central), and soon built up its impressive following with a half-hour "in which children ceased their play automatically, and mother's only problem was to avoid being crushed in the rush to the television set." It was anything but a typical show; as Whitney notes, Tillstrom "broke all the rules." There was no script—each episode ran on what Whitney calls "a stream-of-consciousness-type 'inner dialogue' " between Fran and Tillstrom, who played all the puppet voices. There was no extravagant staging, just a simple puppet stage. The show's humor was low key and smart, with occasional performances of the classics, such as their famous production of "The Mikado" by the "Kuklapolitan Art Theatre and Light Opera Group." And while audiences might not have been huge, they loved the show; when it was cut from 30 to 15 minutes in 1951, the network was swamped with protests, even though the remainder of the half-hour was filled by The Bob & Ray Show, a show whose dry comic tone actually complimented Kukla's).

To be on the safe side, Amory took with him, to the screening, a five-year-old friend, "widely known as the terror of kindergarten," and before they sat down to watch, the boy's father suggested Amory notify his next of kin, just in case. No need for concern, though; "Before Sesame Street, the young man's previous attention-span record—clocked in nursery school during the demolition of a blackboard—was 12 seconds. With us, he sat through two hours of Sesame Street—we saw two shows. He loved every minute and, at the end, was still riveted." The real merit of the show lies in how it's so good that children won't even be aware that it's good for them, which must be every parent's dream. It's targeted at inner-city kids, but it's not exclusive to them. And the Muppets tackle the race issue deftly; "The only kids who can identify along racial lines with the Muppets," Jim Henson says, "have to be either green or orange."

Amory singles out several people for praise: Joan Ganz Cooney and her staff, responsible for the show in the first place; and the four human hosts, Gordon, Susan, Bob, and Mr. Hooper. They all have a warmth that draws children to them; they're the kind of people you'd want your own children to know. Other members of Henson's team, including Carroll Spinney and Frank Oz, also come in for mention. I've mentioned before that I came to Sesame Street quite late in life; I was a teenager when I started watching, out of self-defense at the afternoon drivel on the commercial station that broadcast to the World's Worst Town.™. The lessons went over my head (although I can still count to 12 in Spanish), but the interaction between the Muppets, particularly the humor injected to maintain the attention of parents, was and is terrific. (See Exhibit A.) The Children's Television Workshop, and Sesame Street, remain controversial today, but that's not what this is about. Concludes Amory, "We guarantee you will enjoy all of them not just as much as your child but, better still, as a child." Or, I would add, an adult.

l l l

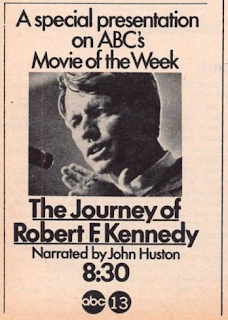

It wouldn't be quite right to segue straight from Sesame Street to soap operas, although I think you'll be entertained when we do get to it, so I'm going to stop off at ABC's Movie of the Week, which presents one of its most unique and unconventional offerings ever: its only non-fiction movie.

Movie of the Week premiered in September 1969, and over the course of its run (until September 1974) proved to be one of ABC's most popular programs, well-loved by many even today. It introduced pilots for series such as Kung Fu, The Immortal, Alias Smith and Jones, and Longstreet, in addition to movies that stuck in the memory: Duel, Trilogy of Terror, Brian's Song, The Night Stalker and The Night Strangler (neither of which were technically pilots), and That Certain Summer. But somewhere between The Over-the-Hill Gang and How Awful About Allan, it found time to slip in a documentary: The Journey of Robert F. Kennedy (Tuesday, 8:30 p.m.) Produced by David L. Wolper, written by historian and Kennedy intimate Arthur Schlessinger, narrated by John Huston, and with a score by Elmer Bernstein, The Journey of Robert F. Kennedy was part of ABC's effort to address social issues and connect to younger viewers and utilized home movies, news footage, still photos, and interviews. As Michael McKenna says in his Movie of the Week history, The ABC Movie of the Week: Big Movies for the Small Screen, "With decades of hindsight, it is difficult not to read the film as an indirect eulogy for the entire decade of the 1960s, and the ideals of many who lived through the era."

What makes The Journey of Robert F. Kennedy so unusual, to my way of thinking at least, is that it appears within the Movie of the Week format, rather than as an ABC News Special or standalone timeslot; Judith Crist makes an oblique reference to this in her movie reviews, saying it was on "the most serious level" of the week's premieres. Since ABC commissioned Wolper to make it, it's not as if the network had to scramble to find a place for it. It had been less than two years since Kennedy's assassination, and it was a wound that was still open for many people; McKenna's statement that the documentary fit the demographic that ABC sought for the movies seems the most logical answer. Still, I can't remember any instance of a documentary being shown as part of a regular movie series—Saturday Night at the Movies, for example, or The CBS Sunday Night Movies. Docudramas, yes, but not a documentary. The closest you can come is probably something from NET Playhouse in the 1960s. For an original movie of the week, it's a curious, but creative, choice.

l l l

Watching Movie of the Week means missing the first half-hour of NBC's own made-for-TV flick, one that is decidedly not creative, at least in the sense that we've seen the fish-out-of-water plot play out many times over the years. This one works, though—it's McCloud (Tuesday, 9:00 p.m.), the origin story for the series of the same name, starring Dennis Weaver as Marshal Sam McCloud, who's come all the way from New Mexico to the big city, i.e. the Big Apple, escorting a prisoner who winds up being kidnapped, with McCloud winding up entangled in a murder investigation. He's joined by Mark Richman as Chief Clifford (who'd be played in the series by J.D. Cannon), and Terry Carter as Sgt. Broadhurst; he'd continue in the role for the entirety of the series.

McCloud was unavailable for preview, which means Judith Crist doesn't review it, but its success causes it to appear in the network's fall schedule, as part of its Four in One wheel series. For season two, it moves to the NBC Mystery Movie series, where it remains for six additional seasons. There are only 45 episodes in total; for all its popularity, it never becomes a weekly series—but then, neither does Columbo, which just goes to show that sometimes being creative just means doing things a little differently.

l l l

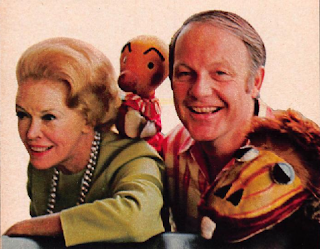

One of early television's most creative programs was Burr Tillstrom's Kukla, Fran and Ollie, the beloved children's puppet show (with hostess Fran Allison) that, not unlike Sesame Street, attracted an adult audience as well; among the more famous fans of the Kuklapolitans were Thornton Wilder, Richard Rodgers, Ruth Gordon, Orson Welles, Tallulah Bankhead, Kurt Weill, Lillian Gish, and John Steinbeck. After many years away, Kukla, Fran and Ollie returns to television this month, with five weekly half-hour specials on 167 NET stations, beginning February 4 (episode 3 airs Wednesday at 8:00 p.m.). The story of the show's rise and fall, as told by Dwight Whitney, is a classic case of how television has failed in one of its essential missions: to provide programming that is intelligent, entertaining, and educational to children, regardless of commercial success.

Kukla began on Chicago television in 1947 before moving to NBC the following year (airing daily at 6:00 p.m. Central), and soon built up its impressive following with a half-hour "in which children ceased their play automatically, and mother's only problem was to avoid being crushed in the rush to the television set." It was anything but a typical show; as Whitney notes, Tillstrom "broke all the rules." There was no script—each episode ran on what Whitney calls "a stream-of-consciousness-type 'inner dialogue' " between Fran and Tillstrom, who played all the puppet voices. There was no extravagant staging, just a simple puppet stage. The show's humor was low key and smart, with occasional performances of the classics, such as their famous production of "The Mikado" by the "Kuklapolitan Art Theatre and Light Opera Group." And while audiences might not have been huge, they loved the show; when it was cut from 30 to 15 minutes in 1951, the network was swamped with protests, even though the remainder of the half-hour was filled by The Bob & Ray Show, a show whose dry comic tone actually complimented Kukla's).

What eventually did in Kukla, Fran and Ollie was television's evolution to a ratings-based system. Pat Weaver, who was NBC's programming chief at the time, recalls that "Burr's history was one of great charm and style, not boffo humor. He was not massively successful in the ratings." Adds David Levy, former VP of programming at the network, "I think he was the victim of a TV structure that had to reach the greatest number of people irrespective of specialized program content. It went off for the same reason Playhouse 90, Studio One and The Voice of Firestone did. These specialized programs [worked] in the early days because it was not yet necessary to reach the tremendous masses." He then adds the coup de grace: "It may have been too good." Says Newton "Vast Wasteland" Minow, Tillstrom's friend and longtime attorney, "Anything on TV a long, long time seems to require replacement. I think that's wrong, especially in children's programming." NBC let the contract lapse in 1954. ABC, which picked up the show, lost interest in 1957; and, until now, that was that.

Tillstrom is pleased to be back on TV, working with NET; it's revived interest in the Kuklapolitans, and in December they appeared on The Hollywood Palace. He's also pleased for the success of Sesame Street as well. But he hasn't forgotten the experience of being on television; "I asked myself who in his right mind would go back into television anymore—except to make a bundle?" He says he doesn't need the money, that the only important thing is to "do my thing," but he adds, "Not that I don't like to be paid, but it’s all economics! Take the Money and Run! Ugh! The real question is what can we do for people? Then I thought maybe that question will come back into fashion again. After all, we are talking about the most powerful communications force the world has ever known." It's 53 years later, and we're still asking that question.

l l l

I suppose I'm contractually obligated to take a look at what else is on this week, so here we go.

Mr. Magoo is back this week, in an animated hour-long special, Uncle Sam Magoo, that takes a look at American history (Sunday, 6:30 p.m., NBC), with everyone's favorite nearsighted character as our guide. Magoo, you've done it again! Wisely, CBS waits until Magoo is over for it's own animated special, a rerun of He's Your Dog, Charlie Brown (Sunday, 7:30 p.m.) Like so many of the non-holiday Peanuts specials, this one just doesn't have the staying power of the rest. And although The Hollywood Palace left the airwaves last week, that won't stop us from checking out the guest cast on The Ed Sullivan Show (Sunday, 8:00 p.m., CBS): Michael Parks of Then Came Bronson; six-state heavyweight champ Joe Frazier (who fights for the world title tomorrow night)*; the Supremes, making their first TV appearance without Diana Ross; Arte Johnson of Laugh-In; actress-singer Michele Lee; and comic Robert Klein.

*Muhammad Ali had been stripped of his title due to draft evasion; a tournament was held to select his successor, and was won by Jimmy Ellis. Frazier declined to participate in the tournament, feeling Ali should not have had his title taken away; he defeated Buster Mathis, and was recognized as champion by the boxing commissions in six states, including—most importantly—New York State. Frazier's fight tomorrow is a unification bout against Ellis; Frazier dominates the fight, which is stopped after the fourth round, and becomes undisputed heavyweight champion.

NBC presents a pair of specials Monday night, beginning with a Bob Hope benefit for the Eisenhower Medical Center in California (9:00 p.m.); a star-studded audience, including Mrs. Mamie Eisenhower; astronauts Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman and Walter Schirra; Terence Cardinal Cooke; Gov. and Mrs. Nelson Rockefeller; and 11 Medal of Honor winners, gather in the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City to be entertained by Bob, Bing Crosby, Ray Bolger, Johnny Cash, and Raquel Welch. That's followed at 10:00 by The Return of the Smothers Brothers, with Peter Fonda, Glen Campbell, David Frye, David Steinberg, and Bob Einstein. Pat Paulsen is on hand as well, and Fredd Wayne plays his trademark role of Benjamin Franklin in a bit that includes Paulsen as Abe Lincoln and Frye as LBJ.

On Tuesday, Jackie Gleason sits down for a rare television interview with David Frost (8:00 p.m., syndicated), in which he talks about men and women (men have mother complexes, and you can't lie to women); love (it means giving); comedy (comedians have to be good actors, as indeed Gleason was); success (you have to hurt somebody to get it); the occult ("there is absolute proof that ESP exists); and happiness ("How can you be happy when people are dying in Vietnam?"). And on Friday, the KOVR late movie is Stranger on the Run (11:30 p.m.), with Henry Fonda, Anne Baxter, and Then Came Bronson's Michael Parks. I wonder if he's the one on the run?

l l l

Finally, that soap opera article I promised you. It's written by James Lipton—yes, the James Lipton of Inside the Actor's Studio. As many of you probably know, he was quite the renaissance man: actor, writer, producer, and even lyricist. (I always thought that if What's My Line was ever brought back in its old format, with tuxedos and everyone being called mister or miss, he would have been an ideal host.) He wrote for The Edge of Night and The Doctors, and was the head writer for Another World, The Best of Everything (which he also created), Return to Peyton Place, and Capitol, so if anyone's equipped to talk about soaps, it's him. And he's here, in a very long but interesting article, to defend the soap as legitimate.

After all, he points out, 20 percent of network revenue comes from daytime television. And daytime means the soap opera, since nine of the top ten most popular daytime shows are soapers. So why are they so popular? Because of the hold they have on their viewers. "Compared with the daytime audience, nighttime viewers are bored, dispassionate and fickle." Nobody calls the station because the Western heroine has been tied to the tracks, but "when I was writing a daytime serial, the mere hint that a scheduled wedding might not take place brought floods of nervous calls, not just to the stations but to the program's production office in New York."

Lipton discusses and dismisses one theory for their popularity: that "it takes place in the intimacy of their living rooms," just like the viewer's own life does. But then, so do many nighttime shows, and their fans don't react the same way. (Unless they're Trekkers.) His own belief is that it's because soap operas are real. "This must sound like an extraordinary, even a reckless, claim in the face of the customary criticism of the soaps: that they are bathetic, sentimental and trapped in a morality that could have made Queen Victoria beam." But let's go back to that joke I told a moment ago about the heroine tied to the railroad tracks. The difference, Lipton asserts, is that there's no suspense about her being rescued; "no matter what jeopardy threatens his heroes and heroines, [the viewer] knows that, one way or another, they'll survive. How does he know? Simple. They're already scheduled for a return next week, same time, same station; a glance at the pages of this very magazine will assuage whatever fears the program may have aroused."

On the other hand, when a soap's characters are put in jeopardy, "they may just die—and the viewer knows it." Our threats aren't the same as the nighttime hero faces; nobody living a regular life faces those kinds of obstacles. But our world is much like that of the soap opera; "Our cancers really kill, and childbirth has all the hazards of the real even. If our heroines sip coffee and worry about their children or their love affairs or the fidelity of their husbands, it is because our viewers sip coffee and worry about their children or their love affairs or the fidelity of their husbands." Soap operas are domestic drama, "but we are, in large part, a domestic society."

As for the accusations that soaps are second-class productions, he asks us to remember that they're either broadcast live (some still were, even in 1970) or recorded life on tape; their flaws and fluffs are no different than those from Studio One and Playhouse 90. This excitement, in turn, is attracting an increasing number of first-rate writers; Lipton himself, in addition to writing soaps, has authored the best-selling book An Exaltation of Larks. and he says this not to toot his own horn (although that, too), but because it demonstrates how serious writers are being drawn to work for soaps. As we've seen, the theme today has been creativity, and according to Lipton, the most creative writers are working in perhaps the most creative genre, soaps.

The bottom line is that those who criticize soap operas probably haven't seen them for awhile. Their audience is a discerning one; "When I was playing Dr. Grant on The Guiding Light, the three most loyal and vocal fans I had were Lena Horne, Cole Porter and Tallulah Bankhead; I wouldn’t call them undiscerning." And when he has an itch to create contemporary drama, it's the soap opera to which he turns. It's an interesting argument he makes; I'm not sure I agree with all of it; I never was a fan of them, and there aren't many left on TV, but when I've been in doctor's waiting rooms where one has been on, I've noticed an awful lot of sex and skin, with people who are almost uniformly beautiful and handsome. Now, maybe this is a reflection of the People magazine type of culture we've become rather than what it really is, but with plastic surgery as popular as ever, maybe not. I'm sure books have been written on this topic, and perhaps some of you have your own opinions. But, based on what Lipton writes here, either my respect for the soap opera is increasing, or my respect for popular culture is decreasing. TV

"It's 63 years later, and we're still asking that question." - Do you mean 53 years (since 1970)? I've seen "Kukla & Ollie" on the 1970s MATCH GAME, and behind them was a box (where Tillstrom obviously sat or knelt). When discussing KF&O and MATCH GAME, a funny memory (probably of most MG fans) comes up. A female contestant had just won a game and was playing the Super Match. When asked for a match to "Cuckoo (blank)" she said "Cuckoo, Friend, and Ollie". Here's a link to the clip for anyone who hasn't seen it or wants to see it again: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gqGgJYgtS04

ReplyDeleteFixed.

Delete