February 27, 2023

What's on TV? Thursday, March 4, 1965

Tonight Perry Como takes his Kraft Music Hall Americana road show to Boston for a live telecast from the new Boston War Memorial Auditorium, now known as the Hynes Convention Center. Once Perry stepped down from the weekly grind of hosting Music Hall, the show returned as a monthly series of specials, held in different parts of the country. Dating back to 1963, the show was staged live from cities including Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Dallas, New Orleans, Minneapolis, Chicago, and even Burbank. I know we don't have variety shows anymore, but it would be nice to see the country like this again; I think some of the late-night shows have gone on the road from time to time, usually to team up with some other event, like the Super Bowl, being carried on the network. Of course, Carson used to take The Tonight Show to California for a couple of weeks while he was still based in New York, but it would be nice to see some occasional on-location shows from American landmarks. I mentioned that this show was live, but because we're looking at the Northern California issue this week, it's being shown on tape-delay. These listings are certainly live, though!

February 25, 2023

This week in TV Guide: February 27, 1965

Imagine, if you will, a popular television show with a mystery at the core of its plot. This mystery has become central to its core of loyal fans, who can't keep from speculating on the show's outcome. Theories and countertheories are proposed, viewers reach out to the producers with suggestions, and even the show's stars are confronted in public by those demanding to know what's going on behind the scenes. There's even a theory, labeled "wild speculation" by some, that the producers already know how the show will end, that the final episode has already been written, and that some people have even seen it via bootleg videos, and this theory has gained such a following that it's become the subject of a national magazine, with denials being issued that only fuel the speculation. It's nice to have such devoted fans, but still . . .

The Sopranos. Mad Men. Breaking Bad. Game of Thrones. Yes, of course, to all of them. But remember, this is 1965, and the series in question is The Fugitive.

It's a little hard to say how or where this rumor started, but as Henry Harding's "For the Record" feature recounts, this rumor, "running rampant around the country," which

has been detailed in hundreds of letters to TV GUDE and Fugitive producer Quinn Martin, says that the final episode of the series has been shot, has already been shown on some stations, and that the one- armed man did not kill Dr. Kimble’s wife after all. In the episode, the one-armed man purportedly tells Dr. Kimble that he saw Lieutenant Gerard do it—during what appeared to be a lovers’ quarrel. They haven’t actually seen this episode, the letter-writers say, but they know people who know people who have.

As if to prove the accuracy of this observation, the week's letters to the editor section includes a letter from Mrs. Janice F. Angevine of Shreveport, Louisiana, who says that this "wild rumor" is "running rampant over the city of Shreveport and environs." "It says The Fugitive’s last chapter has been written and actually shown in some cities and that policeman Gerard is the real killer of Kimble’s wife. Kimble, in the last episode, finally finds the one-armed man who tells a horrendous tale of a love affair between Lt. Gerard and Mrs. Kimble, and reveals that Gerard killed her."

Harding quickly dismisses the rumor; with The Fugitive currently ninth in the Nielsens, "Dr. Kimble may still be running long after the rest of us have stopped." Producer Quinn Martin hasn't given any thought to a conclusion (in fact, he was against the idea of bringing the mystery to a close, fearing that it would damage the show's prospects in syndication), but doesn't mind the attention. "People ask me, 'Isn’t it awful about all these rumors?' I say, 'what’s awful about it?' " Martin speculates that The Fugitive may have tapped into a universal theme, probably the fear of being accused of something you didn't do, and adds, "It’s marvelous that people care so much about the show."

|

| (L-R) Morse, Janssen, Raisch |

As far as The Fugitive itself, this shows how quickly the series gained traction with viewers. It's only been on for a year and-a-half, since September 1963. Fred Johnson, the one-armed man (played by Bill Raisch) had only appeared in three episodes to this point, and one of those was a flashback; that people are, even then, speculating on a showdown between Kimble and Johnson is, although inevitable, quite interesting. Most intriguing of all is this idea that some parts of the country have already seen the final episode, although it's always been the friend of a friend of a friend who saw it. Something like this would have been a fairly significant story—when the final episode did air, it drew a record audience—so the thought that it could have been "sneaked" onto only a few stations is absurd. And yet, it shows that being media savvy wasn't the norm back then; people weren't conditioned to think that way. You and I may know that a network would use the suspense of a final episode to whip up a tremendous amount of publicity prior to its airing (just look at "Who Shot J.R.?), but I don't think people stopped to think about that in 1965; other than a "very special" marriage episode of a series, storytelling didn't work that way.

In any event, it's fun to read a contemporary account of this. The Fugitive was less than halfway through its four-season run, and Gerard would always remain a favorite suspect in the minds of viewers (people wanted him to be the bad guy); one version was that the series would end with Gerard unscrewing a fake arm, and David Janssen and Barry Morse used to joke that it would end with the two of them going off together into the sunset. While that final episode isn't the best of The Fugitive, it gave viewers what they wanted: a conclusion. It also gave ABC what it wanted: ratings.

l l l

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup.

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup.Sullivan: Ed presents a show from Florida’s Miami Beach Auditorium. Scheduled guests are comedians Alan King and Bill Dana; the singing Barry Sisters; dancer Juliet Prowse; singer Wayne Newton; the singing Hialeah Jockey Octet; the Hurricanes, the University of Miami’s Glee Club; the Sensational Leighs, aerial act; and the Cypress Gardens Water Skiers.

Palace: Co-hosts Roy Rogers and Dale Evans (accompanied by Trigger and the Sons of the Pioneers) introduce comedian Shelley Berman; rock ‘n’ rollers Jan and Dean; the Ballet Folklorico of Mexico; the Nicholas Brothers, singing dancers; the Murias, Japanese jugglers; and the Flying Armors’ trapeze act.

I think this is one of those weeks where when it comes to picking the winner, your mileage may vary. I look at Roy Rogers and Dale Evans and see a couple of legends; I look at Shelley Berman and see one of the best satirists of the time; I look at the Nicholas Brothers and see two of the most dynamic singer-dancers ever captured on film. That doesn't mean Sullivan doesn't have a good lineup this week; in fact, I think it's a bit deeper. But you can already tell which way I'm going, can't you? The Palace rides off with the prize.

l l l

While looking at the Hollywood Palace lineup, I was drawn to a program on KQED, the educational station in the Bay Area: Freberg Revisited . . . Again (Saturday, 9:00 p.m. PT) Professor Edwin Burr Pettet of Brandeis University visits (for the third time) Stan Freberg, who discusses "his philosophy about the commercial aspects of show business." Pettet was a noted expert on comedy and drama in the theater, and it would have been a natural for him to be talking with Freberg, who applied comedy to the art of advertising in a way that was revolutionary, or at least highly successful. Freberg's satiric radio series was very funny, as were his television appearances, and yet I think we most remember him for commercials like this one for Jeno's Pizza Rolls, perhaps one of the greatest of all time. Imagine what he could have done with the Super Bowl commercials.

Here's another interesting show: Profiles in Courage (Sunday, 6:30 p.m., NBC), which, of course, is based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book by then-Senator John F. Kennedy. The original profiles in Profiles were too few to fill up a television series (there were only eight, and they were all Senators), so prior to his assassination JFK authorized the inclusion of additional subjects. Tonight's subject is one of those additional biographies: Andrew Johnson, future President of the United States, but at present a senator from Tennessee, staking his prestige and his future on a fight to keep his state from seceding and joining the Confederacy. Walter Matthau stars as Johnson, in yet another reminder of what a fine dramatic actor he was, and how interesting his career might have been had he continued in that vein.

Had Kennedy lived, one of the added profiles might well have been of John Glenn, the most heroic of the astronauts whom Kennedy so admired. Glenn is with Walter Cronkite on the CBS Special Report "T-Minus 4 Years, 9 Months and 30 Days" (Monday, 10:00 p.m.), an investigation on the progress of the American manned space program, and whether or not the United States is still on track to land a man on the moon by 1970. The report, taped earlier this afternoon, includes a test of the Saturn V booster supervised by Dr. Werhner von Braun in Huntsville, Alabama. I like that, and I also like tonight's episode of I've Got a Secret (8:00 p.m., CBS), in which Buddy Hackett subs for panelist Bill Cullen, and Lorraine Bloy, a stewardess chosen from the audience last week, sits in for vacationing Bess Myerson.

I know that space is limited in TV Guide listings, and sometimes you have to take shortcuts to describe the plot of an episode, but here's one for The McCoys (Tuesday, 10:30 a.m., CBS) that I would have redone: "Kate thinks Luke doesn't love her—he's not as affectionate as her neighbor's husband." I'm sure they're not suggesting that her neighbor's husband is more affectionate to Kate than Luke, right? Better to ignore that and check out The Bell Telephone Hour (10:00 p.m., NBC), as host Robert Goulet is joined by Eydie Gorme, Mildred Miller, Barbara Cook and Susan Watson to tell "The History of the American Girl." Sounds to me like something you'd see on one of NET's sociology programs.

Fellow Rat-Packers Sammy Davis Jr. and Peter Lawford appear as themselves on The Patty Duke Show (Wednesday, 8:00 p.m., ABC), as Patty is tasked with finding a big-name star for the high-school prom. They didn't have that problem in the World's Worst Town™, the big name would have been whoever could come up with the keg for the after-prom party. And speaking of big-name guest stars, they're always available at Burke's Law (9:30 p.m., ABC); this week's lineup includes Joan Bennett, Edd Byrnes, Arlene Dahl, Paul Lynde, and Bert Parks.

One of ABC's standbys is The Donna Reed Show (Thursday, 8:00 p.m.), coming up to the end of its seventh season, and while the focus is on Donna and her family, one of the featured characters is 36-year-old Bob Crane, who plays Dr. David Kelsey, next-door neighbor and colleague of Donna's husband, Alex. Marian Dern profiles Crane this week, looking at the life and motivation of one of the busiest men around, described as a combination of Jack Lemmon, Bob Cummings, and Jack Benny. Not only is Crane a regular on the Reed show, he's also one of the most popular DJs in West Coast radio, host of the morning show on KNX, the CBS flagship in Hollywood—a job that nets him a cool $75,000 a year. It's said that this is the best way to understand Crane and his frantic mix of "records, interviews (frequently testy), news items, commercials, kidding, claptrap and corn," and isn't afraid to have fun during the show's commercials, such as one for an airline during which he plays the sound of a motor sputtering and dying in the background. Advertisers seldom complain, and why should they? "They get three minutes for every one they pay for." He's leaving the Reed show next fall; Dern portrays Crane's relationship with Tony Owen, Reed's current husband and producer of the show, as a somewhat contentious one, an opinion that isn't always shared by contemporary reviewers, but not to worry: he's shooting a pilot for CBS, a World War II sitcom called The Heroes. Don't bet against him.

You may remember a few weeks ago I spent almost the entire space here commenting on creativity (or the lack thereof) of television shows, which—naturally—means I'd notice the debut episode of The Creative Person, a 28-week series that "probes the personal vision of the artist—those qualities which enable the creative person to translate the world around him into a meaningful statement." (Friday, 4:30 p.m., KQED) Let this sound too stuffy, tonight's episode, "A Thurber's Eye View of Men, Women and Less Alarming Creatures" is a comic recreation of Thurber's view of the world based on his writings, starring Eddie Bracken, Elaine Stritch, Elliott Reid, and Allyn Ann McLerie. Halla Stoddard, the producer of Broadway's "Thurber Carnival," did this adaptation.

l l l

How about some golf? Nowadays, there's plenty to be found between the men's and women's tournaments each week, not to mention the Golf Channel. But back in the day, televised tournaments were few and far between, aside from the major championships. And yet there's no shortage of golf this weekend, thanks to the made-for-TV events offered by the networks and in syndication. A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned the CBS Golf Classic, which features two teams of pro golfers each week leading up to the championship. This week, a quarterfinal match pits Billy Casper and Bob Rosburg against Bo Wininger and Tommy Bolt. (Saturday, 3:30 p.m.)

NBC's long-running Shell's Wonderful World of Golf, which in its original incarnation ran from 1961 to 1970, showcases not only the finest golfers but also some of the best and most scenic courses in the world. You can find that on Sunday at 4:00 p.m., as Canadian champions George Knudson and Al Balding face off at Cape Breton Highlands in Nova Scotia. There's also Big Three Golf, a series of filmed rounds contested by the three best players in the world: Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, and Gary Player. Eight matches are scheduled for the season, and you can see the third on Saturday at 2:00 p.m, on KCRA, or the fourth on Saturday at 4:00 p.m. on KRON. Gotta love those syndicated schedules.

So why were these so popular? Because they're filmed, the broadcast can be edited to make sure viewers see every big shot, regardless of when it happens (the average round could take between three and four hours back then); you also don't have to deal with those long breaks between holes. Because the productions take care in their camera placement, they can also bring the best views of the action. And it compares favorably to tournament golf, which was generally limited to the last three or four holes, by which the outcome might already be determined, the best shots missed, or the leader already being in the clubhouse as the broadcast starts; you're also assured of seeing the biggest names without having to worry about them missing the cut or being out of contention. There are a number of them at YouTube; they're worth checking out.

Speaking of tape-delay (or film-delay, as the case may be), we have another example of it with ABC's Wide World of Sports, and coverage of the seventh annual Daytona 500 (Saturday, 5:00 p.m.), which was held two weeks ago. As with golf, a 500-mile race can take a long time to run, and showing an edited version of it can save a lot of dead airtime. The first live coverage of the race was in 1974, when ABC joined it in progress for the last 90 minutes, using taped highlights to update viewers on what had happened prior to the start of the live telecast. The first flag-to-flag coverage of the race came on CBS in 1979. But back to 1965—the race is stopped after 133 laps due to rain, with Fred Lorenzen coming out on top.

l l l

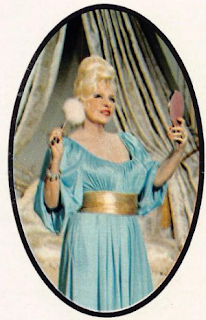

I hope people remember who Mae West was; Dwight Whitney calls her "the first, the funniest, and, some say, the greatest of all the modern sex symbols," and as recently as this issue, audiences are still accepting her invitation to "Come up and see me sometime." Last season, her tongue-in-cheek appearance on Mister Ed was one of the year's comedy hits, and she's hoping to make a return appearance this season. Whitney's interview with West takes place, naturally, in the boudoir, where "Everything is gilt on white. The walls are white, the carpet is white, the tufted satin bedspread on the round bet is white, the satin canopy rising majestically to the ceiling is white." She says she's been in high demand lately, estimating that she's turned down "more movie and TV offers in the last 10 years than most girls get in a lifetime." Why? "Because they are not right for me. They are not Mae West."

She has a lot to say about today's actresses, most of it critical. Of family sitcoms the aforementioned Donna Reed Show, she replies absently, "Donna who?" Jean Harlow was "merely acting sex," she calls Lana Turner "a schoolgirl," and when asked about Marilyn Monroe, she says, "Well, they managed to do something with her." And then there's Elizabeth Taylor. She's a face," West says. "Of course, she has some blood in her veins. But that thing with that fellow—uh, what's his name?—didn't do her any good. Women won't come to see you. Of course, I haven't seen Cleopatra."

She's about to talk about her plan for two TV specials each year when she's reminded her agents are waiting, and it's time for Whitney to go. She doesn't tell him to come back up and see her sometime, but she does say, "I'm waiting for pay-TV. I'll bet I'll rate No. 1 on it." It's a ridiculous statement based on her age (72), but in the coming years she'll appear in the movies Myra Breckinridge (1970) and Sextette (1978), be interviewed by Dick Cavett, write a second book and a play, and do an album with covers of songs by The Doors. At age 84, Time will say, "Mae West is Still Mae West." It's perhaps with that in mind that Whitney concludes that he won't bet against her.

l l l

MST3K alert: Teenagers from Outer Space (1959) "A spaceship arrives on earth carrying some youngsters. David Love, Bryan Grant." (Friday, 1:00 a.m., KRON) What this brief description doesn't tell you is that the "youngsters" are bent on conquering the Earth through the use of a monstrous "Gargon." I could explain their motive for this, but there's no percentage in it. And yes, they are teenagers, more or less. TV

February 24, 2023

Around the dial

I wonder what the Nelson family is watching tonight, don't you?

In the early 1970s, we saw a number of new shows being fronted by movie stars, such as Glenn Ford, Yul Brynner, and Anthony Quinn. At Comfort TV, David looks at one of those: the series Shirley's World, with Shirley MacLaine as a magazine photographer. How bad was it? See what David has to say.

The Hitchcock Project continues at bare-bones e-zine, and this week Jack introduces the works of Oscar Millard, starting with the final-season episode "Consider Her Ways," a nasty little story with Barbara Barrie and Gladys Cooper that definitely bears watching.

At Cult TV Blog, John remains in the 1980s with the game show Sticky Moments, another of those marvelous British shows that defies explanation. At least I'm not going to attempt it, because I couldn't do any better than John, so see what he has to say about it.

It seems as if I'm usually linking to A Shroud of Thoughts for Terence's obituaries, so this week I'll try something different with his retrospective on the short-lived Sammy Davis Jr. Show. I wrote about this series in the early days of the blog, but I think Terence can give you a much better feel for the challenges the show faced.

If you've ever heard the Big Finish audio adventures of Doctor Who (they're very good, with many of the original actors participating), you'll be enthused by their release of 12 hour-long stories continuing The Prisoner, with Mark Elstob as Number 6. Find out more about it from Martin Grams.

Not TV-related, but well-worth reading, is The Hits Just Keep On Comin', where JB remembers the disasterous Rolling Stones concert at Altamont in 1969. It's another reminder that when you traffic in nostalgia, it brings along the bad times as well as the good.

Here's a question that I've never even considered before, but now I'm fascinated by it: "Can you recall which Twilight Zone episodes had a mid-point narration?" Thanks to Paul at Shadow & Substance, we now know: I'll admit I wouldn't have thought of any of them. Brilliant! TV

February 22, 2023

What I've been watching: January, 2023

Shows I’ve Watched: | Shows I've Added: |

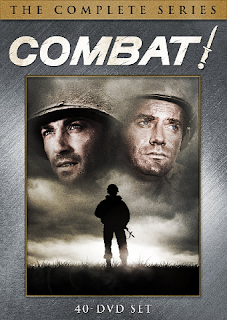

Combat! | Twin Peaks (Original) |

Captains and the Kings Sam Benedict Omnibus (Interviews) | |

The Rat Patrol can be fun at times to watch (although it seems to me that the quality started somewhere in the middle and went steadily downhill), but it strikes me as a Saturday morning version of war: all thrills and action and leaping jeeps, fine if you're an energetic boy playing war with your friends (or on a video game), but it never puts you in the middle of what's happening, makes you ask yourself what you'd do in a situation like this.

Combat! tells the story of an American unit, beginning with its D-Day landing on the beaches of France and continuing as they make their way toward occupied Paris, and it has to be one of the grimmest, grittiest programs to air on television during the 1960s. It surrounds you with war: when the shells fall, you feel yourself flinching; when the soldiers are covered with muck and grime, you want to scrub it all off your face and hands and feet, if you can even remove the boots that you feel like you've lived in for half your life. Most of all, it puts you in the middle of a line of American soldiers running toward German lines, running straight at guns that are shooting at you. It makes you wonder what you'd do. It makes you wonder how they did it, day after day, living in a kind of boring anxiety where you have to fight off hours of routine knowing that a bomb or a mine or a sniper could appear literally at any second. How do they relax? you wonder. How do they live their lives with such a heightened sense of danger constantly hanging over them? Why would you wish this on anyone?

If I make this sound grim and depressing, the kind of show that makes you want to take a handful of Prozac, then the most remarkable thing about Combat! may be that it never fails to keep your interest. It takes you into the horrors of war, yes, but it also takes you into the lives of these men, men who've learned how to do all the things I mentioned because, in James Burnham's words, "When there's no alternative, there's no problem." You learn to do what you have to do, and if you don't exactly become used to it, you do come to terms with it. These are the kind of characters that make it easy for viewers to root for them, to become vested in their welfare, perhaps even to identify with them. And that's before you even get to know them.

The alternate leads in Combat! are Rick Jason, who plays the leader of the platoon, Lieutenant Hanley; and Vic Morrow, who plays the veteran Sergeant Saunders. The episodes starring Morrow generally focus on the missions of him and his men, checking out seemingly deserted towns or doing reconnaissance work to sniff out German troop locations; Jason's episodes deal with the challenges of being in command or leading special missions. Each will occasionally appear in the other's episodes, although in a more incidental role, and many of the stories are built around guest stars and their own stories; it's a mark of the excellence of the writing and acting that the stories of rear echelon replacements, played by character actors, can be as engrossing as that of a tank commander who before the war was a failed priest, played by Jeffrey Hunter.

Several factors enhanced the show's realism; for one thing, most of the cast and crew had served in either WWII or Korea, and knew what it was like to slog through the mud of combat. Executive producer Selig Seligman (don't you love that name) was so insistent on creating a realistic environment (knowing, of course, that many of the show's male viewers would have served in the military as well) had the principal cast go through a week of basic training at Fort Ord; Jason would later say that it was harder than his actual basic training in the Air Corps.* In addition, the show was blessed with talent behind the scenes, beginning with Robert Altman, who directed ten episodes in the first season; The most frequent directors during the show's run were Bernard McEveety and John Peyser, but Richard Donner, Burt Kennedy, and Tom Gries also worked on the show, and Vic Morrow himself directed seven episodes.

*One of my favorite stories, according to the always-reliable Wikipedia: "During the battle of Hue during the Vietnam war US troops trying to retake the city, not having been trained in urban combat, resorted to using tactics for assaulting buildings and clearing rooms they learned from watching Combat!, reportedly to great effect."

While Jason and Morrow are the above-the-title stars, the unit is comprised of a very tight group of supporting players, each of whom gets opportunities to play crucial parts in stories. Pierre Jalbert (Caje), Jack Hogan (Kirby), and Dick Peabody (Littlejohn) all remained with the show for all five seasons; Conlan Carter (Doc) is in the final four. One of the most interesting casting decisions was that of stand-up comedian Shecky Greene as Braddock, serving mostly as comic relief. Although he only appears in the first season, he shines in a lighter episode where he is taken prisoner by the Germans, who mistake him for a colonel (Keenan Wynn). He repeatedly tries to convince the Germans he's really just a private, until he realizes he can leverage their misidentification into getting better treatment for his fellow prisoners; it's a fine example of rising to the occasion.

As was the case with so many of the best dramas of the 1960s, Combat! has a terrific lineup of stars, both current and future, in guest appearances; in addition to the aforementioned episode with Jeffrey Hunter, you've got Lee Marvin (in a great second-season episode), Roddy McDowell, Ed Nelson, Harry Dean Stanton, Leonard Nimoy, Mickey Rooney, Jack Lord, Robert Duval, Charles Bronson, John Cassavetes, Sal Mineo, James Coburn—the list goes on. Some of them are rough and tough heroes, while others are simply trying to hold on through the next barrage. And there are no guarantees that they'll make it intact to the end of the episode; there is no false sentimentality involved. In fact, as the series progresses through the first season, you see the combat vet Sanders struggling to accept the death of yet another member of his unit; in one memorable scene, he recalls how he didn't even know the first name of one of his men, a replacement who gets killed during a scouting mission, and determines to avoid that in the future.

One of the most striking episodes of the series is an Altman-directed first-season story, "I Swear by Apollo," which finds the men holed up in a French convent with a gravely injured French operative. Their mission is to get him to French intelligence so he can give them vital information. Without a doctor, they are forced to kidnap a Nazi doctor (Gunnar Helstrom) to perform life-saving surgery. Virtually the entire final act is conducted in silence—no music, no dialog, only the sound of the Frenchman’s labored breathing. Altman’s hand is evident in the way the act cuts between scenes of the surgery, the soldiers watching as burning candles drip wax, the contemplative nuns silently praying in their chapel, the sweat on the brow of the doctor (Sanders has threatened to kill him if he allows the Frenchman to die) and a large Crucifix mounted on the wall, the crucified Christ looking down from the Cross upon the makeshift operating room. It’s gripping television; there is no guarantee that the Frenchman will survive the operation, and the confidence viewers would have from watching a regular in the same situation is not present. In the end, the Frenchman lives, but one of Saunders’ men, critically injured by a mine, dies despite the doctor’s efforts. As the doctor prepares to leave (it would have been against the rules of engagement to take a doctor prisoner), he asks Saunders if he would have cared about the Frenchman so much if he didn’t have military information; Saunders, in turn, asks him if he would have worked so hard to save his life if it hadn’t been under threat of death. The war takes its toll on the living as well as the dead, a message that comes through in virtually every episode of the series.

Combat! runs for five seasons—longer, as more than one person has pointed out, than the actual campaign that took the troops from D-Day to Paris. For the final season, the show transitions from black-and-white to color, and I don't think the series is served well by that change—warfare, like pool halls, is more fitting when it's done in B&W, not to mention color makes it a bit easier to tell when they're shooting on a backlot. But no matter how it's photographed, there's a weight to the battle scenes and the drama that still comes through, that still makes Combat! television's definitive war drama.

You'll recall my favorable review of Garrison's Gorillas, the series which preceded Combat! in the Hadley Tuesday night lineup. Where the two shows differ, though, is in tone. Garrison's Gorillas is well-written and well-acted, but the emphasis—which works quite to the show's advantage—is on action and adventure. Combat!, however, focuses on the micro view of war; not the maps and the battles, but the human stories and the human cost of war. It carries an avowedly anti-war message, but one that, unlike, say, M*A*S*H, is not ideological. It is a show that makes clear that war is sometimes unavoidable, sometimes necessary, but something never to be sought, never to be glorified, never to be used as a political solution—a Pax Americana, say—by those who fight in the trenches. It presents war the only way it should be experienced: on television.

l l l

Believe it or not, that's all there is to report this month; we're at a point right now where the schedules have been running pretty smoothly for awhile. But, as you can see from the "Shows I've Added" column, there are more in the pipeline, just waiting to take their rightful place in the primetime schedule. Next time, things should look a little different. TV

February 20, 2023

What's on TV? Thursday, February 21, 1980

Reviewing this week's Kentucky edition of TV Guide put me in a nostalgic kind of mood. Not for these particular shows, necessarily, but for what it was like to come home from school every afternoon and turn on the TV. I talk frequently about being old, because I am old—but it wasn't during their original runs that I watched shows like Gilligan's Island on Channel 11 or McHale's Navy on Channel 9; it was by watching them after school. That's when I was introduced to the Francis the Talking Mule movies on Channel 4, having no idea that the human acting opposite Francis was the legendary Donald O'Connor. And though I didn't bother to watch Star Trek or Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea when they were on the networks, I watched them around dinnertime on Channel 11. Part of what makes the memory of a show so strong, so special, is when and where you watched it. It makes afterschool memories special as well, as if simply being out of school wasn't special enough. What kind of afterschool TV memories do you have?

February 18, 2023

This week in TV Guide: February 16, 1980

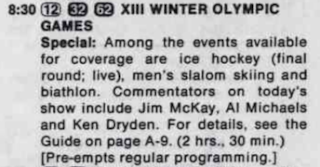

We'll cut right to the chase: the United States plays the Soviet Union Friday night in the medal round of the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid at 8:30 p.m. ET on ABC, with the U.S. completing the first half of the Miracle on Ice by shocking the Soviets . To show you how things have changed in the last 43 years, that 8:30 broadcast was tape-delayed; the puck actually dropped at 5:00 p.m. ET. Not that ABC didn't try; they'd asked the International Ice Hockey Federation to change the game time to 8:00 p.m. so that it could be broadcast live in primetime, but the Soviets objected; that meant the game would air at 4:00 a.m. Moscow time instead of 1:00 a.m. So, the Russkies won out, and the game was played as planned.

When I say this shows how things have changed, I have two examples in mind. First, it's difficult to believe that the Federation would turn down an American network today, considering how much money that network would have paid for the rights to the Olympics, not to mention the importance of the U.S. television market. Second, considering the excitement leading up to the contest, it's likely the American network would preempt regular programming and carry it live. Yes, I know affiliates had more sway back then, and their local newscasts were always a big deal; but if you're a station manager, would you want to take the chance of being called un-American by viewers for not carrying the game? And it's not like there haven't been precedents involving sports; golf tournaments, World Series games, and NCAA tournament games had been butting into local airtime for years.

Anyway, with the advent of the internet and social media, it's all a moot point; it was hard enough in 1980 keeping the outcome of the game a secret, because people could tune in to the radio for updates. (In Minnesota, which supplied many of the players for the U.S. team, radio stations were carrying live simulcasts of the CBC radio broadcast. Other markets probably did as well. Before the game aired, ABC's Jim McKay was upfront in telling viewers that they game had already been played, but he promised not to reveal the final score. (ABC's announce team of Al Michaels and Ken Dryden had called the game live as it happened, so there was no chance of them spilling the beans either.) All the people in the background behind McKay celebrating and chanting, "USA! USA!" might have been a clue, though.

Today, the game would be shown live whether it started at 5:00 or 8:00, whether it was on NBC or Peacock. I do think that most people who watched it that night tried to avoid finding out who won, though. It's not unlike watching a game you'd recorded a couple of hours earlier; if you really want to be kept in suspense, you'll find a way. (At least until you get home from work, to be greeted by your 6-year-old daughter yelling, "We won, daddy, we won!") Maybe the Soviets would have been better off showing the game at 4:00 a.m. at that.

l l l

On weeks when we can, we'll match up two of the biggest rock shows of the era, NBC's The Midnight Special and the syndicated Don Kirshner's Rock Concert, and see who's better, who's best.

Kirshner: Music by Rufus and Chaka Chan, Squeeze, Tanya Tucker and Rupert Holmes: comedy by Jimmie Walker and Dick Lord. Songs include "Do You Love What You Feel?" "Lay Back in the Arms of Someone." "Blind Love." "Escape."

Special: Bonnie Pointer (hostess). Electric Light Orchestra. Nicolette Larson and the Spinners. Also: a comedy segment with Bruce Vilanch and Rufus Shaw Jr. Songs include "I Can’t Help Myself," “Heaven Must Have Sent You" (Bonnie); Last Train to London" (E.L.O.); "Let Me Go, Love" (Nicolette).

I'd be interested in seeing what my friend JB would think of this matchup. I always watched The Midnight Special, going back to my days in the World's Worst Town™ when I had no other choice. So perhaps there's a bit of sentiment going. Rupert Holmes is very talented (thought I'm not a big fan of all his music), and I don't know either of the comedians on Special, and a lot of the time that would be enough to tip the scale. But I've always really liked ELO, and that's what's enough for me to take Special this week.

l l l

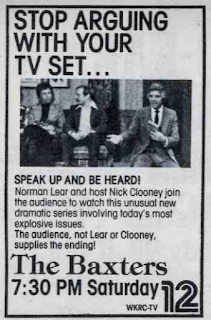

Have you ever heard of a Norman Lear show called The Baxters? (Saturday, 7:30 p.m., WKRC in Cincinnati) It started out in 1977 as a local show on WCVB in Boston, and was then nationally syndicated from 1979, when Lear took over the show, to 1981. The gimmick to The Baxters is that half of the show consists of a situation faced by the Baxter family (husband, wife, three kids); the other half featured a live studio audience who, having seen the first 15 minutes, would discuss the issues raised in it and offer their opinions. As the ads say, "You supply the ending!" The way the show was marketed was that there was a national version of the studio discussion which the stations could use, or they could produce their own studio discussion and insert it in the show. In this week's episode, "Nancy will have nothing to do with the new handgun that Fred has purchased to protect the family." The always-reliable Wikipedia calls it a sitcom, but with a writeup like that I suspect it might have been more like a dramedy.

I confess that I've never heard of either this program or its premise. I was about to say that it was probably because it hadn’t been shown in the Twin Cities, but when I went to YouTube seeking some clips, one of the first to come up was a commercial with Lear plugging the show, made for—KSTP, St. Paul-Minneapolis. (Not surprisingly, KSTP chose the local segment route; that's what their archrival, WCCO, would have done. Both were heavily invested in local content at the time.) So there goes that excuse. No, this is simply a show I never watched, never was interested in, never remembered. And it's not likely that we'll see anything like it again anytime soon, since nobody watches TV shows at the same time, except for football. C'est la vie. And look at who the host of is on the Cincinnati edition—Nick Clooney!

l l l

Here's something else I don't remember: "The Greatest Man in the World," an adaptation of a whimsical James Thurber story, on the series American Short Story (Monday, 9:00 p.m., PBS). Brad Davis stars as Jack Smurch, the world's newest aviation hero, who managed to pilot his plane on the first solo flight nonstop around the world. Smurch is the subject of Lindbergh-like adoration, but there's one problem: the man's a total jerk. Even his mother "wouldn't have been sorry to see her son make an unscheduled landing in the Atlantic." This won't do for the latest national hero, though, so a newspaper editor, reporter, and the Secretary of State get together to practice John Ford's advice about printing the legend. In addition to Davis, the cast includes Carol Kane as Smurch's girlfriend and Howard da Silva as the editor, and Henry Fonda is the host of the series.

|

| Thurber's rendition of Jack Smurch |

At least I can understand not remembering this one, because I would have been watching the Olympics (I watched every kind of sports back then, on the grounds that "Something might happen.") But I'm beginning to wonder about these various programs I have no memory of. Is it possible that I don't remember classic television as well as I thought I did? Is it possible that there were more forgettable shows out there than I was aware of? Or am I just getting old? No, it's not that. Is it?

l l l

The Olympics are, as you might expect, the dominant force on your TV screens this week, although ABC performs a little trickery, slipping in an all-star Family Feud with ABC sitcom stars on Monday and an episode of Charlie's Angels on Wednesday. Each one pushes the Olympics back an hour. (Fox has been notorious in modern times about doing this to events like the World Series.) CBS and NBC aren't going to go black, though, so let's take a look at counterprogramming on a typical night of the week—Tuesday, let's say, because both of them seem to be pulling out the stops. The main Olympic events are ice dancing, speed skating, and skiing; the latter two events would have been tape-delayed.)

Last week we saw a tour de force hour by Anne Bancroft; this week, we see a similar hour of creativity helmed by Goldie Hawn and Liza Minelli. Goldie and Liza Together (9:00 p.m., CBS) team up in a showcase for the two to "sing and swing and even act," an ironic description in that they each have won Academy Awards for their acting. (Maybe someone was trying to demonstrate their dry wit with that copy, in which case he failed.) I do wonder who came up with the idea of pairing the two, though? It says "First Time Together"; did they have any previous history of being friends, of having performed together other than on TV? Did Liza wake up one morning and call her agent and say, "You know, I've always had this dream to act with Goldie Hawn, and my life won't be complete without it'? Did the public demand it? It just doesn't seem to me to be a logical pairing, but perhaps someone can enlighten me.

Anyway, they display their musical talents in three production numbers, including one in which "Goldie camps it up to 'Y.M.C.A.' with body builders and gymnasts," which I admit leaves me feeling a bit queasy. they then turn serious for a rendition of "The Other Woman," and play New York City roommates in a dramatic vignette; and bring down the curtain with an all-singing, all-dancing finale. Here's the whole show; see what you think. Personally, I'm partial to Anne, but it's nice to see that even in 1980, there was some variety on the airwaves.

That's followed by a Bob Newhart special (10:00 p.m., CBS), a comedy hour that's billed as his "first comedy special," although it might be a lot like Newhart's variety show that he hosted back in 1961. I like Newhart a lot, and I suspect this is a pretty funny show, although the addition of guest stars like Lawanda Page and Joan Van Ark do give me a moment's pause; what Newhart really needs to succeed is a good straight man, and I don't know if either of them would fit the bill.

NBC's main counterprogramming is The End (9:00 p.m.), Burt Reynolds's very black comedy about a man coming to terms with his impending death; it runs the gamut from "the satiric to the sensitive to the slapstick," with Dom DeLuise best of all as "a moon-faced murderer."

So here's what you have to pick from on Tuesday. What would you have chosen? And how effective is the counterprogramming scheduled by CBS and NBC?

l l l

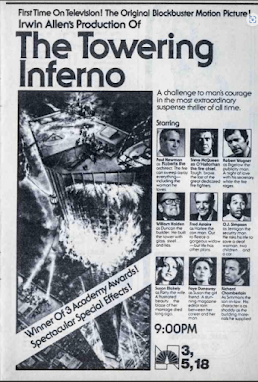

Well, that's a good question. What are some of the highlights of the rest of the week? NBC brings out a big gun with the television premiere of The Towering Inferno, shown in two parts. (Sunday and Monday, 9:00 p.m. each night) Judith Crist calls it "a cardboard spectacular," with its moral being that "firemen, the salt of the earth, ought to design buildings because architects are megalomaniacs, contractors cooks, and building codes antique." On the other hand, it's hard to beat an all-star cast with Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, Robert Wagner, William Holden, Fred Astaire, Faye Dunaway, Robert Vaughn, O.J. Simpson, and others.

Simpson also shows up in Detour to Terror (Friday, 9:00 p.m., NBC), and no, that's not the story of the white Bronco chase; he plays the driver of a tour bus hijacked by "three weirdos." Crist says it's "slick but satisfying," but I wonder how many people watched it instead of the Miracle on Ice?

Not that all we have to choose from are specials and movies; CBS has its solid Sunday night (60 Minutes, Archie Bunker's Place, One Day at a Time, Alice, The Jeffersons, and Trapper John, M.D.) and Monday night (M*A*S*H, House Calls, and Lou Grant) and NBC does the same on Wednesday (Real People, Diff'rent Strokes, Hello, Larry, and The Best of Saturday Night Live; Thursday night they offer Buck Rogers, Quincy, and the short-lived drama Skag, with Karl Malden. Friday at 8:00, NBC has a one-hour takeoff on This Is Your Life with Donald Duck as the honoree and Jiminy Cricket as the host. It's a repeat; otherwise, I think it would have been better-served on Sunday night.

There's not much else that jumps off the page, unless you're in the mood for a Republican presidential primary debate from New Hampshire. I don't know if it takes place as scheduled (Wednesday, 9:00 p.m.), but there's another one that occurs the following week, at which Ronald Reagan reminds everyone that he paid for the microphone.

I wonder, though; I haven't paid enough attention the last few years to see how the networks counterprogram the Olympics. Do they, or do they cede the weeks to NBC? And since we're told that the Olympics now attract a mostly female audience (with its soap-opera infused storylines emphasizing American athletes), would they program the same kinds of movies and specials that they did here?

l l l

About television technology: try this on for size.

"New technology will enable viewers to call up stock prices, medical advice—a wealth of data—on their screens."

That's the subheading of Neil Hickey's article on what we can expect to see with the television of the future; the only thing that he didn't anticipate is that the screen would not be on our televisions, but on our phones. And that, because so many people would be watching video content on their phones, that this was the new television.

The technology that Hickey describes—called teletext, which has been available in Great Britain for several years—allows viewers to choose from "about 800 'pages' of printed material that are continually being broadcast (invisibly until requested) right along with regular programs." It's transmitted encoded on unused space on the TV signal. The encoded signal can be accessed through a television equipped with a special decoder. The information we'll be able to access is, theoretically, unlimited: news, sports results, stock market prices, weather, traffic, radio and TV logs, job-hunting information, home-study courses—the lot. The TV could also be used as an encyclopedia and dictionary, "as well as the 'note paper' for an electronic mail and message service and a convenient way to communicate with the deaf." Email, in other words. The whole thing would probably look and feel like the pre-Windows version of a PC. Fascinating.

Another option is a system called viewdata, which is transmitted over phone lines; "a viewer simply places a phone call to a viewdata computer in which is stored, for easy retrieval, all manner of useful information and services." The specially equipped set is connected to the phone by an adapter—a modem! The accessible pages come from "information providers" such as the British Library, the British Medical Assocation, Reuters, Barclays Bank, and the New York Times, that pay to have their information included. At the moment, it'll run you about $2,000 (in Great Britain) for a set like that, but when they begin to be mass produced, experts think they may cost as little as $25 to $50 more than the average set. A cable-compatible TV!

Granted, Hickey points out, a number of observers, including some network executives, are skeptical of this "Buck Rogers stuff" and aren't even sure the public will want this kind of service. But Paul Zurkowski, president of the International Information Association, scoffs at the doubters. "That's what all those monks who were copying manuscripts back in the 15th century said when they first heard about printing. The future shock will be momentous." One French television executive says that TV-computer services "to the home via telephone or satellite communications provide an exciting potential in our view." Everyone agrees that should it come to fruition, the networks will be involved, seeing it as a source of new advertising revenue—which could result in a battle with their own affiliates to control the market. As Hickey concludes, "the fuse has definitely been lit and pretty soon we'll know just how big a bang this information explosion will be."

What's remarkable about this article is not that everything, for the most part, came to pass. The explosion Hickey envisioned was in reality just clearing the way for the information superhighway. If anything, the experts underestimated what would be possible; the future delivered more than they predicted. That it intimately came to fruition not on our televisions, but on our telephones, makes it even more remarkable. That's kind of cool, considering we still don't have the flying cars from The Jetsons.

l l l

MST3K alert: First Spaceship on Venus. (German: 1962) An expedition (Yoko Tani. Oldrich Lukes. Ignacy Machowski) intends to explore the planet’s mysteries. (Friday, Midnight, WXIX) Warsaw Pact science fiction! Also known as The Silent Star, it was actually an East German/Polish collaboration; for its dubbed release in the West, a Soviet cosmonaut was changed to an American astronaut. Hey, with dubbing anything is possible! According to the always-reliable Wikipedia, the author of the original novel, Stanislaw Lem, was less than impressed "and even wanted his name removed from the credits in protest against the extra politicization of the storyline when compared to his original." One of his comments: "It practically delivered speeches about the struggle for peace. Trashy screenplay was painted; tar was bubbling, which would not scare even a child." In other words, perfect for Mystery Science Theater 3000. TV

February 17, 2023

Around the dial

We'll start this week with a leftover from last week, as F Troop Fridays returns to The Horn Section. Hall looks at the episode "Captain Parmenter, One Man Army," and if you remember the series, you know that's a recipe for disaster. Find out what happens to Fort Courage when everyone but Parmenter is suddenly out of the Army?

At Cult TV Blog, John has moved on from The Prisoner and starts a series on TV shows from the 1980s, beginning with Scully, which has nothing to do with The X-Files and everything to do with the surreal depiction of the life of a British schoolboy. Any other attempt to describe it would be useless, so check out John for all the details.

We'll stick with British TV for a moment, or at least TV with a British connection; Cult TV Lounge explores Hammer Films' 1980 TV series Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense, a co-production with Fox that should have worked, but didn't. Find out why, and whether or not it had anything to do with Hammer's American partners.

At Drunk TV, Jason looks back at the first season of Magnum, P.I. (the original, which as we know is the only real one), and tells us how Thomas, Rick, T.C., Higgins, and that dynamic Ferrari combine with the gorgeous Hawaiian landscape (and a few shapely adorables along the way) to produce a show that's much loved all these years later.

Speaking of Magnum, Realweegiemidget takes a gander at the sixth episode from that first season; Gill tells us how this episode, "Skin Deep," is a tribute to the noir classic Laura, with Tom Sellick assuming the Dana Andrews role of the detective trying to find out who killed Laura—er, Erin.

Over at Comfort TV, David shares the top TV moments from the great Sammy Davis Jr. As David mentions, few big stars appeared on episodic television as often as Davis did (occasionally playing himself), and his appearances on shows from Zane Grey Theatre to Charlie's Angels, with a little All in the Family thrown in. Who can beat that, besides the Candy Man?

Finally, Tim McCarver, one of the most familiar voices on baseball broadcasts of the last few decades, and a pretty fair player as well, died Thursday, aged 81. Here's a look back at his career, and the impact that he made. TV

February 15, 2023

The Descent into Hell: The Brotherhood of the Bell (1970)

Imagine, if you will, that you’re a member of an organization—a society, let’s call it. Membership in the society is exclusive, by invitation only, and its purpose is to place its members in positions of influence in business, politics, finance, and academia, so you were greatly honored when you were invited to join. To be a member is a privilege, but not one you can share with others; not only can you not tell your colleagues, your friends, your family, even the very existence of the society is a secret. Through the years, you’ve attained the wealth and power that was promised, but there’s a catch: in return for the advantages you’ve been given, the society may call on you one day to return a favor, one consistent with the status you’ve attained. It’s an offer you won’t be able to refuse, and you know what that means, because once you become a member of this society, there’s no backing down, no way out.

Is it the World Economic Council, the Trilateral Commission, the Freemasons, the Illuminati?

Or is it the Brotherhood of the Bell?

l l l

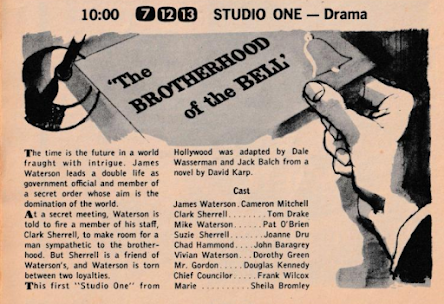

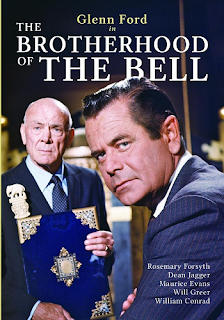

David Karp’s 1952 novel, The Brotherhood of Velvet, has been adapted twice for television under the title The Brotherhood of the Bell: once for Studio One on January 6, 1958, with a script by Dale Wasserman and Jack Balch; and again on September 17, 1970, for CBS’s Thursday Night Movie, this time produced and written by Karp himself. Despite differences in each of the three versions, the story is essentially the same: a decent man caught in a trap between his duty to an organization to which he has belonged for his entire adult life, an organization that has played a role in everything he has accomplished; and his duty to himself, his moral code, and his individuality.

The Brotherhood of the Bell, a society of men who graduated from the exclusive College of St. George in California, is presented as a singular honor, reserved for the best and the brightest. Its members are among the most powerful and influential men in the world, the elites of business, finance, academia, and politics. (When a new member comments that he’s now part of the establishment, he’s told, “We are the establishment.”) To be a member of the Brotherhood is to be set for life—professionally, personally, financially. There a catch, however: in one of the Brotherhood, members must pledge “absolute obedience and absolute secrecy,” and promise to do whatever is asked of them if they’re called upon to do a favor—no questions asked.

At the time, it was generally believed that the Brotherhood was based, at least in part, on Yale’s Skull and Bones society, an organization that has included many of the world’s leaders in, well, business, finance, academia, and politics. Its members have included U.S. presidents and presidential candidates, cabinet members and Supreme Court justices, publishers, corporate executives, and intelligence agents. Two of its members were George W. Bush and John Kerry, who faced each other in the 2004 presidential election; in his autobiography, Bush described Skull and Bones as “a secret society; so secret, I can't say anything more,” a description that both Bush and Kerry reiterated when asked by Tim Russert on Meet the Press.

In the book and the Studio One production, our protagonist, Jim Watterson (played by Cameron Mitchell) “lead[s] a double life as government official [with the State Department] and member of a secret order whose aim is the domination of the world.” In Karp’s 1970 version, which is available on YouTube and DVD and which we’ll be using as the primary reference point, his name is Andrew Patterson (Glenn Ford), a respected professor working at a prestigious institute. In either case, he’s about to find out just what it costs to “belong” to the Brotherhood of the Bell.

l l l

|

| Dean Jagger (L) and Glenn Ford |

He has been assigned to prevent a close friend and colleague of his, Dr. Konstantin Horvathy (Eduard Franz), from accepting a deanship at a college of linguistics—a position that the Brotherhood has reserved for one of their own. Patterson is given a list of names of agents who helped Horvathy defect to the United States from behind the Iron Curtain, and is told to blackmail Horvathy by threatening to reveal the names of these agents (virtually guaranteeing their deaths) unless he declines the position.

Already apprehensive about the assignment, Patterson tries desperately to convince Horvathy to turn down the position; when he refuses, he hands Horvathy a copy of the list and tells him what he will be forced to do. Horvathy, a political refugee and lifelong opponent of communism, is shocked by Patterson’s revelation and feels betrayed by his old friend; rather than buckle under the threat, he commits suicide.

Horvathy’s death has a profound effect on Patterson, who knows that it was his pressure that caused the suicide. Patterson is sickened by his role in the death of his friend, and how the Brotherhood (with his cooperation), has taken away his humanity, he falls into a depression that is, what? Self-loathing? Suffocating guilt? A desire for revenge? The hope of redemption? All four?

In order to scourge himself of the effects from his membership with the Brotherhood, Patterson becomes determined to bring down the Brotherhood. He first confesses, and I think that’s the right word, to his wife Vivian (Rosemary Forsyth) about his involvement with the Brotherhood, as a way to explain the depth of his guilt. She suggests he talk with her father, Harry Masters (Maurice Evans), a powerful real estate tycoon with a knack for knowing the right thing to do. Taking Patterson’s story seriously, Masters introduces him to Burns, a federal agent who tells assures him that the government is aware of the Brotherhood, and takes the instructions and list of names from Patterson to use in the investigation.

So far, so good. But when Patterson goes back to the location where he met the agent, he finds there is no agent and no sign of the office in which they met. He contacts the agency (obviously the FBI, although not referred to by that name), and they tell him they don’t have any agent Burns. Patterson, increasingly alarmed by this turn, tells them to call Masters to confirm his story, but his father-in-law denies any knowledge of their conversation or the meeting with Burns, and suggests that his son-in-law is on the verge of a mental breakdown due to recent events.

The pressure on Patterson mounts. the foundation financing the Institute eliminates his department, putting him and everyone else who works with him out of a job. He flies to San Francisco to confront Harmon and threatens to expose him, but Harmon accuses him of ingratitude toward the Brotherhood and then delivers the crushing blow: it is because of the Brotherhood that he’s had had every job, received every fellowship, even met and married his wife. They even arranged for the construction company owned by Patterson’s father Mike to receive important contracts, making him a millionaire. “You have never competed for one thing in the 22 years since you took your oath at sunrise,” he tells Patterson, and while it’s vital to his belief in himself to think otherwise, deep down he fears it’s true. The media ridicules him and the DA refuses to investigate; today they’d call him a Conspiracy Theorist, and accuse him of wearing a tinfoil hat.

|

| Patterson tells Vivian to "get out" |

Patterson reaches the nadir when he appears on a local talk show to discuss the Brotherhood and is humiliated by the host (William Conrad at his malevolent best; think of a cross between Morton Downey Jr. and Jerry Springer). Even more demoralizing is his discovery that the only people who take his accusations seriously are crazies and other conspiracy buffs. Patterson touches off a brawl in the studio, and winds up in jail.

l l l

We probably ought to pause for a moment here and take stock of where we are.

Earlier, I mentioned differences in the three versions of Brotherhood of the Bell. In Karp’s novel and the Studio One version, Watterson (the Patterson character) works for the State Department, and is asked to fire his assistant and friend, Clark Sherrell and replace him with a member of the Brotherhood. The betrayal is that much more personal; Sherrell is not just a colleague, but Waterson’s assistant. Further, the evidence which they want Watterson to use against Sherrell is that he engaged in homosexual activity when he was a teenager. It’s a charge that’s very much of its time; both the communists and the anti-communists were known for using the homosexual angle in blackmail. Not having seen the Studio One version of Brotherhood, I don’t know if 1950s television would have gone there; since the names and premise are the same as in the book, I wouldn’t be surprised that it was some sort of sex scandal such as infidelity that was substituted.

(Incidentally, that 1958 Studio One production is said to be set in the near future: 1976. That would have been the Bicentennial year, the 200th anniversary of American independence. Is there a message to that, a reminder of what the country was founded on?) And despite the lurid paperback cover, the issue of sex is incidental to Karp’s story; if anything, it’s used as a metaphor for what it means to be a man—to be independent, to think for yourself, to stand on your own two feet and make your own life. Having just found out that none of his accomplishments have been due to his own efforts, Watterson has been, in a sense, emasculated. This same feeling is accomplished through other means in the 1970 production, but the net result is the same: a hollowed-out man, a man at his most vulnerable.

l l l

One of the most tender of all human vulnerabilities is the secret, and there is a reason why so many of us are so sensitive to it. Whether it be the diary of a teenage girl, the pseudonymous writings of a blogger, or the innermost confidences we share with a best friend, a secret exposes our most intimate thoughts and provides something of a window into the human soul: the hopes and fears and aspirations, but also the guilt and the wrongdoing and the unmasking of the truth. One of the reasons why the Catholic Church maintains the inviolability of the Seal of Confession is that reconciliation with God demands nothing less than complete, total honesty regarding sin, a candor that can be achieved only through its confidentiality.

Is it any wonder, then, that the thought of having these secrets exposed in public, whether to anonymous strangers, co-workers, or our own family and friends, chills our bones and fills us with an inexplicable dread? Even reality stars, who often seem to have no secrets whatsoever (nor any shame), use their shows at least partly to maintain control over the revelations of those secrets. Just look at what happens when some frenemy spills the beans: tears, screaming, and slap fights abound. And let’s face it, they still have secrets. Listen to what they admit, and then ask yourself how embarrassing must be those things they wouldn’t admit. (And while you’re at it, ask yourself as well if you don’t think them capable of doing those very things.)

We've gotten used to losing privacy in the name of convenience; what's security when compared to being able to have Siri take care of your needs just by saying the word. But the thought of an organization that as a file on you, filled with those secrets that you'd rather never see the light of day—that seems to cross a line for people (unless, of course, you're the one gathering the information). We’re outraged, offended, filled with rage. “You have no right!” we say. But in the very next instant, we’re overcome by dread and fear. What if someone were to find out? The secrets could be trivial embarrassments, law-breaking admissions, or something in-between; it might even be something that’s not your fault, but is difficult to explain. It makes no difference. It’s why blackmail never goes out of for style, and private detectives never go out of business. (It’s also why so many blackmailers wind up being murdered, at least on television.) Many people—maybe most—would do anything to keep those secrets from becoming public.

There’s one thing that we understand, though: there’s something wrong about an organization that collects and uses this kind of information. It is itself a secretive organization: a government agency, a public safety department, an organization filled with nameless, faceless bureaucrats, a human resources department; and it trafficks in all kinds of personal information, from your race to your "gender identification" to your vaccination status. This information could cost you the chance at a job, a loan, a business transaction; they won't really tell you how it comes into play, and the fact that they deal in secrets while remaining secret themselves is the icing on the cake. The people in charge of these organizations may use various rationale to justify their actions: national security, for instance, or public safety, or the ever-popular diversity. They may say that their goals are noble ones, such as the public good, or the survival of the planet; like your parents, they may say that it hurts them more than it does you. But, when they explain it to you this way, they expect you to understand that they’re only threatening to expose you in the name of a higher good. There’s nothing personal about it. It’s even for your own good, and if you don’t understand this, you’re just being selfish.

Or even worse, they’ll start a whispering campaign against you, one that gets louder as you resist them. They’ll accuse you of the worst possible mental illness known to man: being a conspiracy believer. Conspiracy becomes the dirty word of all dirty words, as if the mere suggestion means nothing you say matters.

l l l

And now the ending. One reviewer suggests that for the 1970 production, “apparently some idiot network executive made writer Karp tack on a schlocky hopeful ending”; a review of the book suggests a certain ambiguity; “Is it truly a plot or has Jim lost his mind and imagined it all as a result of paranoid schizophrenia?” Again, it would be interesting to know how Studio One brought the story to a conclusion, but I suspect it would be closer to the 1970 ending; television shows of the 1950s weren’t much for ambiguous endings, but it’s not impossible. But let’s discuss the ending we have, not the endings we lack.

Patterson is bailed out of jail by a most unlikely person: his boss at the Institute for the Study of Western Civilization, Jerry Fielder (William Smithers). Patterson has suspected Fielder of being part of the Brotherhood as well, but now it turns out that Fielder has been doing some investigating of his own, and has found that Patterson has been blacklisted from working for any other academic institutions. He believes Patterson’s story about the Brotherhood, but tells him he must find another member who can verify its existence.

In desperation, he returns to St. George, to Dunning, the man he sponsored for membership at the movie’s opening, and pleads with Dunning to join him—to bring down the Brotherhood for his own good as much as that of the world. “You’ve either got to be at war with them or you’re in their service!” he says. “Come with me and you’re free of the Brotherhood!” At first it appears that Dunning’s loyalties will remain with the Brotherhood, but as the movie ends, he joins Patterson at the airport, apparently enlisting in his campaign.

l l l

It's difficult to know where paranoia begins and ends in a story like this, one that’s equal parts Kafta and Koestler. (The Brotherhood of the Bell has been described variously as anything from a political thriller to a horror story.) One way of looking at it is to see it everywhere: Dunning only appears to join Patterson, but in reality he’s there to keep an eye on him, to eliminate him as a threat to the Brotherhood. But that’s far too cynical for me, and besides, it’s not consistent with the way the scene is played. Dunning has pledged himself to the Brotherhood; Patterson himself is the one who has brought him in. And now Patterson is telling him, in effect, that everything was a lie, that the Brotherhood is an evil organization determined to control the key sources of power in the world. That’s a hell of a shock for anyone to have to absorb; under the circumstances, Dunning’s hesitancy is all too real.

How would we react in such a situation, being asked to turn against an organization we’ve so recently joined, an organization which promises us everything—an organization which Patterson himself built up in prestige? Would we dismiss Patterson and his story as the ravings of a crazy man?

Or would we consider the alternative, that everything Patterson says—about the Brotherhood and about its control over us—is true? Would we be afraid to join Patterson, or afraid not to join him.

It’s that fear that organizations like the Brotherhood count on—and themselves fear.

l l l

In addition to writing seven novels under his own name, David Karp went on to a successful career as a writer for television; besides his script for the 1970 version of Brotherhood of the Bell, he wrote for series from The Untouchables and The Defenders (winning an Emmy for writing in 1965) to I Spy and Quincy, and created the legal dramas Hawkins (starring James Stewart) and The Storefront Lawyers. A recurring theme in his work, as Philip Boakes points out in a forward to one of his Karp’s novels, is “the pressure on the individual to conform,” whether that pressure be applied from the state (as in his script for the Playhouse 90 drama “The Plot to Kill Stalin,” or from society itself in the sense of prestige and position.

In 1955, Karp adapted his novel One, written in 1953, for Kraft Television Theatre. (It was also made into a British TV production the following year.) Described as a “political fantasy” in TV Guide and “dystopian fiction” by others, the story concerns a future society “on its way to a self-proclaimed perfection which consists in dissension having been rooted out and every citizen identifying his or her own interests with those of the ‘benevolent State.’ In order to achieve this aim, an enormous state apparatus has devised a sophisticated system of surveillance, subtle forms of re-education and, if necessary, brainwashing.”

What sets Karp’s stories apart is their timelessness, their ability to offer us a shadowy, shape-shifting antagonist with the ability to adapt to any given period in history. The fear and paranoia, the mysterious masters pulling all the strings—contemporary critics have been quite right to liken it to the McCarthy blacklists and the Stalin purges, but we can also see in in the elite with their secret societies, the government infiltration of organizations deemed “threatening,” the ever-expanding surveillance state, the suffocating conformity of the corporate workplace, the social-media censorship of those who question the official line. They are timeless because the desire for absolute power is timeless, and the determination of the powerful to do anything necessary to keep that power is timeless. They are timeless because evil is timeless, and it doesn’t matter where you live, because evil recognizes no borders.

And yet we can’t deny that times have changed. If evil has always been here, it’s also true that over time, evil becomes less and less selective about those on whom its shadow falls. Perhaps the most frustrating aspect is that those who put this evil into motion don’t even bother to hide their footprints anymore. They follow the plan so closely, so predictably, that it’s as if they don’t care that you know what they’re doing. When confronted with the evidence, they simply whisper a few well-chosen words in a few well-chosen ears—conspiracy—as if that’s all that’s needed to discredit you. Meanwhile it’s still sunny where we stand, and anyway, they didn’t say anything on the morning news about clouds, and you can take it to the bank. Right?

Then night falls, and everyone is as quiet as a church mouse. TV

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)