The time: the early 1960s.

The place: a secret conference room in a secret underground laboratory somewhere in the world.

The audience: a dozen of the world’s top scientists.

As we look in, Scientist A is addressing the group:

"And, gentlemen, I’m pleased to announce that, with another week or two of testing, we will have turned science fiction into fact with the production model flying car!"

A hearty round of applause follows.

Scientist B then stands up. "I believe I may have done my learned colleague one better," he begins. Inserting his hand in his pocket he withdraws a small, metallic-looking rectangle slightly bigger than a credit card. "In a matter of months we will introduce a miniature telephone that not only fits in the pocket, but allows the person calling and the person being called to see each other live and in color!"

A confused murmur runs through the room. "Why would anyone want that?" one of the scientists says, as others nod their agreement.

An important-looking man (for they are all men) sitting at the head of the table interrupts the conversation. "Fellow scientists, if I may have your attention! We have something far more important to consider here than flying cars and miniature telephones. It is nothing less than the survival of mankind. Gentlemen, I am talking about world peace."

The room falls silent.

"We stand here today on the precipice of thermonuclear war. Never before have men had the ability to destroy life as we know it with such ease. Our leaders have proven themselves too impetuous, too ideologically rigid, to be trusted with such power. The average citizen is too occupied with his own problems to do anything about it. Therefore, my colleagues, the duty falls to us. It is up to us, and us alone, to save the world from itself."

There are murmurs of agreement all around.

"I have spoken with several of you over the past weeks," the Head Scientist continues, "and I believe we have hit upon the broad outline of an idea. It is our job today to turn that idea into reality, to come up with a plan that will bring all men together as one to ensure peace and harmony for all."

"But how?" Scientist C asks, on behalf of all the men in the room.

"We must concoct a threat that is so grave, so unthinkable, so overpowering in its ability to terrify, that it will unite all humanity against this perceived, common threat."

"Brilliant!" Scientist D shouts. The rest share their agreement, and the men set about discussing what such a threat would look like.

"Eureka! I’ve got it!" Scientist E exclaims. "What about a deadly virus that infects people indiscriminately and has no known cure. It moves through the air, and spreads so easily and rapidly that it would overwhelm Earth in no time. Imagine how it would bring medical researchers together from around the planet to develop a vaccine, and in the meantime all mankind would be united, regardless of race, religion, gender or creed, to safeguard against spreading the virus for the sake of your fellow man. It would even come with a publicity campaign: 'We’re all in this together.' A motto that would appear on television and radio, on billboards and advertisements, everywhere. Every man, woman and child standing together, united against a common and deadly foe."

"How long would it take to develop this?" the Head Scientist asks, turning to Scientist F, their communicable disease expert.

"Well," Scientist F says after an uncomfortable pause, "we’ve actually been working with one in the laboratory that should be just about ready to go." He hesitates again.

"Wonderful! So, what’s the problem?"

Again there's a pause, and Scientist F clears his throat before continuing. "Well, it’s true that the virus is almost ready. It’s just that. . ."

"That what? Out with it, man!"

"Well, you see, although the virus is extremely transmissible, and it does make some people deathly ill, the survival rate overall is almost 99 percent. Most who die already have severe health problems. A lot of people only notice mild symptoms, and many who have it will never even know it."

"You’re kidding," the Chief Scientist says.

"We could warn everyone how dangerous it is," Scientist F says lamely. "That it will keep evolving, and unless they take the vaccine, once we invent it, they’re sure to die." He pauses. "It could work."

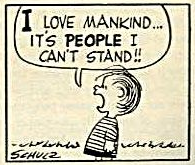

"What the hell kind of threat is that?" Scientist E shouts, rising out of his chair. "You think anybody in their right mind is going to fall for that story? They’ll laugh us right out of town! We’ll look like a bunch of fools, Chicken Littles running around telling people the sky is falling! And they’ll be right!"

"We've got to do better," the Chief Scientist says, disgustedly. "People aren’t that dumb."

Scientist F bows his head and says nothing.

Eventually, the scientists come up with a different plan, one less far-fetched: convince the nations of the world that a foreign invader threatened the planet, and that they would have to band together in order to defeat it. It would work. It had to work.

I

Satire, as Jonathan Swift demonstrated, can be a very effective weapon against what Hannah Arendt called "the banality of evil," to which in this case can be added, "the banality of arrogance."

What you've just read is, more or less and with a certain embellishment, the premise of "The Architects of Fear," a memorable episode of The Outer Limits first broadcast on September 30, 1963, starring Robert Culp and Geraldine Brooks.

|

| And the winner is—Allen Leighton! |

II

At this point, let's take a step back and see where we are so far.

There is something tremendously immoral about what the scientists are up to. Fully in thrall to the "ends justify the means" school, they scheme—for that is what it is, with all its negative connotations— to employ a massive deception on the earth's population. Assuming that this works—and it's a stretch, I think—what kind of megalomania do these scientists have to have to take upon themselves the authority to engage in an act with such global consequences? Who made them God? They were not elected, they were not appointed, they simply take it upon themselves to manipulate the lives of others. It is, without doubt, a characteristic of all dictatorial, totalitarian societies. And where does it end? Having achieved world peace, do they now undertake a similar deception to end other ills? Mandatory sterilization to stop overpopulation? Deindustrialization to end air pollution? Rationing of food to cure obesity? The thing about playing God is that once you go down that road, it becomes pretty hard to pull over to the side.

III

In a 1990 study of scientists in science fiction, Patrick Parrinder writes that "Not only do scientists in science fiction often appear as lurid, melodramatic and evil, but they frequently … evoke the pre-scientific past. That is, the evil scientist—or the future scientist surviving into a post-industrial society—carries with him the trappings of sorcery, wizardry, and alchemy."

IV

If you'll pardon the pun, it doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out that this is destined to go horribly wrong. The transformation of Allen into the alien creature is complete (though not without some nasty reactions), and he is launched into space, to follow a reentry path that will suggest an interstellar voyage, given credibility by an announcement that an alien spacecraft is approaching earth.

|

| Ecce homo? |

It's a deceptively simple ending, and not nearly as abrupt as I'm making it out to be here. It's as tragic as the ending of any Verdi opera, and not because of the failure of the plan to bring about world peace. No, this is tragedy on a human scale, the grandest scale of all, and sets the lie to the famous line near the end of Casablanca, when Humphrey Bogart tells Ingrid Bergman that, compared to the war engulfing the world, their problems don't amount to a hill of beans. No, the tragedy of Allen and Yvette is precisely what hurts so deeply. What doth it profit the world to gain peace and lose love?

All in the name of science.

V

I don't know if C.S. Lewis coined the term scientism—I think he did, but in any event, he certainly provided the modern understanding of the theory, and why it was something to be feared. Lewis defined scientism as "science characterized by principles and practices tending toward controlling rather than investigating nature," resulting in what he termed a "moral devolution of science." In his book The Abolition of Man, Lewis predicted that if "scientific planning [were] cut free from traditional values" it would eventually become "joined to modern ideologies," the result of which would be

a not-so distant future in which the values and morals of the majority are controlled by a small group who rule by a perfect understanding of psychology, and who in turn, being able to see through any system of morality that might induce them to act in a certain way, are ruled only by their own unreflected whims. In surrendering rational reflection on their own motivations, the controllers will no longer be recognizably human, the controlled will be robot-like, and the Abolition of Man will have been completed.

It would be wrong to see Lewis as anti-science, though: As James A. Herrick points out in The Magician's Twin: C.S. Lewis on Science, Scientism, and Society, "Lewis respected scientific work that pursued knowledge of the natural world. Science, for Lewis, was a means of seeing and thus of appreciating nature, and the inviolability of nature was the principal value guiding its investigations. By contrast, the new science, or scientism, developed out of an impulse to see through nature by deconstructing its processes until everything in it—including the human being—was explained as a matter of mere physical causality. Scientism’s ultimate goal is placing all of nature under human control."

VI

As a series, The Outer Limits was always skeptical of science, especially when it was put in the hands of powerful men. "The Architects of Fear" is no exception, for these powerful men, these scientists who thought they could bring the peoples of the world together, were not only trying to create fear; they were acting out of fear themselves. The episode's closing narration:

Scarecrows and magic and other fatal fears do not bring people closer together. There is no magic substitute for soft caring and hard work, for self-respect and mutual love. If we can learn this from the mistake these frightened men made, then their mistake will not have been merely grotesque. It will have been at least a lesson—a lesson at last to be learned.

We have, in our own lifetimes, seen the triumph of scientism, not just in the way we live our lives, but in the terms by which the battle is defined: the words that can be used, the concepts that can be discussed, the opinions that can be held in public. And, as is always the case, to be on the other side is to be not just different but wrong. As Christopher O. Blum points out in the article "C.S. Lewis and the Religion of Science," "It is alarming to learn how the rise and growth of a scientific culture has been linked with the most blatant subjectivism." Now, of course, everything is subjective, thanks to scientism.

And if that subjectivism continues, where does it end? Perhaps Scientist F's flawed virus will not be the last thing to come from that lab. We've already seen vaccines mandated, economies crushed, police states established, and lives destroyed. And then, what? Social credit expanding, healthcare and food rationed, jobs and insurance dependent on whether or not you toe the party line? Life and death itself? And by then, will any of us be recognizably human?

There is, of course, one more lesson to take from all this, one that we would all do well to remember: Except the Lord keep the city, the watchmen waketh but in vain.

And the Architects of Fear will continue to live in the night, and thrive. TV

No comments

Post a Comment

Thanks for writing! Drive safely!