Every time I check on the most-read articles here at It's About TV, the Hogan's Heroes ones are always near the top. Therefore, since I've been writing about my Top Ten favorite series, it seems appropriate to honor the #2 show on the list with this piece from—can it be?—five years ago. And in case you think I'm reading too much into a mere sitcom, I counter that the best way to respect a series is to take it—and the issues it raises—seriously.

Xhen you’ve seen every episode of Hogan’s Heroes as many times as I have, you’re allowed to let your mind wander a bit. By now, I can identify each episode within the first ten seconds, can quote an alarming amount of dialog, know all of Hogan’s scams and how Klink reacts to them, and rest secure in the knowledge that through it all, Schultz never sees anything. It’s all as comforting as a warm blanket in the middle of winter.

So when you’ve seen, say, "Information Please" for the tenth time, you start to pay more attention to the little things, like when Hogan decides the only way to get rid of the German officer threatening their operations is to frame him as a traitor, and Newkirk, after listening to the plan, comments that "We really are a nasty lot, we are." And "The Assassin," when, after discovering that a Nazi scientist is in camp working on atomic research, Hogan declares, "We got to kill him," to which a startled Carter remarks that it "Just doesn’t sound like us, Colonel." And "Hot Money," which involves the Nazis setting up a counterfeiting operation, in which the lead scientist of the operation voices concern over the morality of counterfeiting even during wartime.

These represent some of the rare moments of genuine self-reflection in the series, when, even amid the absurdist humor, the characters dwell on the implications of their actions with an acute awareness of the consequences involved. Setting aside the fact that we’re talking about fictional people in a very improbable setting, you have to ask—what does it all really mean? The storylines in Hogan’s Heroes encompass a wide range of acts, including deception, misinformation, lying, and killing. How does one assess their morality during wartime? After all, just because we’re talking about a comedy, that doesn’t mean truth can’t be found somewhere in the midst. And not just Hogan's Heroes, of course, but other wartime television series as well.

To find the answers to these questions, I decided what I needed was an expert. So I went out and got one.

Dr. Robert G. Kennedy is a Professor of Catholic Studies at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, and his area of expertise includes St. Thomas Aquinas, who did quite a lot of writing about the Catholic theory on Just War. Among other things, he’s presented on topics such as "A Catholic Analysis of Modern Problems for the Just War Tradition," "Is the Just War Theory Obsolete?" and "Is the Doctrine of Preemption a Legitimate Element of the Just War Tradition?" With credentials like this, I figured he was just the person I was looking for. He also knows something about military ethics as portrayed in television and the movies, which made it less likely he'd think I was completely around the bend. "It’s interesting, the questions that a 50-year-old sitcom can prompt," he said after I’d described what was on my mind; then, as a true scholar and gentleman, he gave serious consideration to my questions and rose to the challenge.

"The Catholic tradition since Augustine has held that lying—deliberately asserting to someone as true something that you know to be false—is always wrong. The key word here is asserting." For example, things such as acting in a theatrical performance, telling a joke, and so on, are in many cases not assertions; consequently, false statements on those cases are not lies. (Philosophers often debate where to draw lines, but that’s a question for another day.)

Addressing the question in "Information, Please," in which the boys frame a German officer, Major Kohler, by falsely implicating him as a traitor, Dr. Kennedy continued. "If Hogan makes a false assertion, he is lying and acting wrongly, even if the end to be achieved is worthwhile. On the other hand, if memory serves, the story line in these matters often involved deception (lying is a species of deception, but not all deception is wrong). Suppose Hogan 'carelessly' leaves a forged document someplace where Klink will find it, and Klink immediately draws a conclusion, as he was meant to do, that some officer or another is a traitor"—a fairly common occurrence in the show. "Or suppose Hogan, in conversation with Klink, asks a number of insinuating questions, planting the idea in Klink’s mind that the officer is a suspicious character.

"In neither of these cases does Hogan assert anything, even though he certainly means Klink (and others) to draw conclusions that are false but helpful to Hogan’s aims. In cases like this he has certainly engaged in deception, but he has not lied. Not all deception is morally sound, but in some of these cases it might be." He added, however, that deception intended to cause an innocent person to be harmed, even if it might not be lying, may still very well be immoral, a concern which Newkirk seems to be alluding to in his comments.

By now, I was beginning to understand why I’d wanted an expert.

In the episode "How to Win Friends and Influence Nazis," Hogan’s assignment is to convince Dr. Karl Svenson, a world-famous Swedish chemist working on a formula for a new steel alloy, not to give the formula to the Nazis. Failing that, his mission is to assassinate Svenson, which he’s prepared to do with a small bomb implanted in a pen. To understand the morality of such an action, it’s important to make a distinction—not between military and civilian personnel, as is sometimes supposed, but between combatants and non-combatants. "Some persons in uniform are generally held to be non-combatants, such as chaplains, medics, and perhaps even the JAG corps. But even here, the instant a medic or chaplain picks up a weapon, he becomes a combatant—which is why we generally have very strict rules against these people ever engaging in actual combat. The moment they do so, they contaminate the immunity of all other medics and chaplains. They can say a prayer but they can’t pass the ammunition.

"Strictly speaking, combatants are liable to attack, even lethal attack, even when they are not actually engaged, at that moment, in combat operations. The argument would be that they are still ongoing participants in the wrongful project of the enemy and therefore may be subject to the force necessary to impede their project. An air base, for example, is a legitimate military target, even at night when the personnel are asleep. But there are limits. Injured soldiers in a hospital are likely not combatants, soldiers on leave back home, even when wearing a uniform, are likely not combatants, and so on. In all this, by the way, there is the assumption that it is the enemy who is engaged in a wrongful project, not our own side. We also assume, while acknowledging that this is hard to measure, that the level of force applied should not exceed what is necessary to impede the wrongful project. So, we should not kill enemy soldiers if we can disable them; we should not disable them, if we can persuade them to surrender."

In the case of Dr. Svenson, "though a civilian, [he] is likely a combatant, even if a reluctant one. Even though he is not in uniform, he is engaged critically, if at some remove, in developing weapon components that could be strategically effective against his nation’s opponents"—such action means "he is directly participating in the wrongful project of the Germans and therefore enabling in a proximate way their combat operations.* Is he a legitimate target? Again, there are extremes but here we can talk about the distinction between pre-emptive action and preventive action. Pre-emptive action, which is often justified, seeks to neutralize an imminent threat. Preventive action seeks to neutralize a threat that one can imagine becoming real at some point in the future, but which poses no imminent danger. It is hard to imagine a situation in which preventive action can be justified.

*An analysis that could apply to “The Assassin” as well.

"So, what is the situation with [Svenson]? Is he on his way to deliver the formula for the new alloy to the Nazis or is he merely making progress on developing the formula, and might reasonably succeed, in a month, or a year or two? I would say that if he has the formula and is about to give it to the Nazis, then he probably poses an imminent threat and could be a legitimate target. But probably not if he is merely making progress. We would also want to know how important his formula really is and what other means might be available to prevent the exchange. The answers would address the issue of proportionality." In this case, Svenson tells Hogan that work on the formula will require "two or three month’s more work," to which Hogan replies, "I’ve now got time to convince you to come over to my side." The implication is that Hogan is prepared to do whatever it takes to make killing Svenson a last resort; it’s a wise—and moral—judgment.

Then there’s an episode like "The Swing Shift," in which the men infiltrate industrialist Hans Speer’s cannon-making factory, so they can sabotage the plant with explosives? Assessing this situation requires "sound judgment and attention to details and context," according to Dr. Kennedy; while extreme situations are often easy to resolve, "the closer they are, in fact, to the middle, the less clear they become." Given that factory workers are not automatically considered combatants, any attack, if possible, should be staged when the workers are not working. In "The Swing Shift," however, the plan is for the factory to operate around the clock. What then?

Dr. Kennedy compares this example to the bombing of the famous ball bearing plant at Schweinfurt* "Ball-bearing manufacture was a choke point in the German war industry, as so many pieces of equipment required ball bearings. Destroy the plant and war production would be crippled. It had very high strategic value, not merely a tactical value. A strong argument can be made that harm to the workers was justified by that strategic value."

*Ironically, in this episode, Hogan’s request to London for an air strike is tabled due to higher-priority targets, among which is—the real-life ball-bearing plant at Schweinfurt. It’s not the first time the writers got little details like this correct, and quite possibly the mention of Schweinfurt was designed specifically to justify the sabotage to Herr Speer’s factory (whose name, of course, is an indirect reference to Nazi Armaments Minister Albert Speer).

Overall, these kinds of actions call for careful consideration. Examples of non-uniformed combatants could include “a civilian truck driver delivering ammunition to troops in battle or of a technical advisor helping combat troops to operate complex equipment, and so on.” However, Dr. Kennedy adds, "I am less inclined to say [that factory workers are combatants] in general. One issue here would have to do with what it is they are making? Is it bullets and cannon shells or army boots? Are they building ships or canning vegetables? We usually draw some lines with respect to the proximity of the support provided—the mother knitting socks for her soldier son is not a combatant—and whether the support itself is neutral (that is, not combat specific). In the latter case, we would likely say that the truck driver delivering groceries to a military base is not a combatant since this would be done without regard to war or peace.

"A second issue has to do with timing. Factories don’t move and in principle, therefore, they could be attacked when the workers are not working. In the Second World War, the British bombed Germany at night, when they could not see the target. Their reasoning was that it didn’t matter whether they hit the factory or the workers’ homes: production would stop either way. But Catholics would think that there is a very important difference here.

"A principle of proportionality has to be introduced: is the military objective sufficiently important to justify a certain level of genuinely unintended casualties? One test question is to ask whether we would proceed with an operation if we were bombing (let’s say) one of our own cities that had been occupied by the enemy, and the unintended casualties would be our own citizens. We are on more solid grounds if we could answer affirmatively, as the French did with respect to the bombing of their own railyards immediately before D-Day. At the other extreme, was the bombing of Japanese and German cities in the latter days of the war, when our objective was clearly to use the deaths of non-combatants as leverage to force surrender."

In summary, says Dr. Kennedy, "war is a very messy business. It always involves unintended casualties and collateral damage. Cases like these, and there are a great many, irritate people who want formal rules for all occasions. There are no such rules, which is why prudence is the preeminent practical virtue. And in the difficult cases, the decision maker often lacks some vital piece of information, so in the end we often do the best we can. Here again, the genuinely virtuous person, who will be less swayed by bias or emotion, is more likely to judge well."

By this time I was thoroughly exhausted, but also exhilarated and intellectually stimulated. I thanked Dr. Kennedy not only for his time, but his patience in answering what some people might consider silly questions that read far too much into light entertainment. Looking back on the discussion, it seemed to have justified my decades-long fandom of Hogan’s Heroes (which I think does very well when it comes to ethical choices). More important, it provides us something to think about whenever we watch depictions of war on television (or in the movies)—not to the exclusion of the program’s entertainment value, but rather in amplification of it, complimenting and enhancing our understanding of what we watch. Furthermore, the same questions can be asked of other kinds of shows: police procedurals, for example, or mysteries. It doesn’t matter whether it’s the most searing drama or the silliest comedy—they all play using the same set of moral rules, even if they don’t abide by them.

War forces terrible choices on everyone: not just the combatants, but those who issue the orders sending them into battle, the politicians responsible for making policy, the civilians providing support to their armed forces. We live with the consequences of our choices, and someday we answer for them. How right Robert E. Lee was, when he observed that "It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it." TV

A special thanks to my friend Dr. David Deavel for providing the introduction to Dr. Robert Kennedy.

Showing posts with label Hogan's Heroes. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Hogan's Heroes. Show all posts

February 28, 2024

November 18, 2022

Around the dial

Another easy week in the blogosphere; you'd almost think that people had other things to do besides type about old television shows. But you can't go wrong with a collection that includes a Thanksgiving recipe, right?

Helen Nielsen's third and final script for Alfred Hitchcock Presents was "You Can't Trust a Man," a skillful adaptation of her own short story, starring Polly Bergen and Joe Maross; it's the subject of Jack's latest Hitchcock Project at bare-bones e-zine.

I submit that there's no way you're going to pass up a story that contains the line, "What on earth is going on with Shakespeare's tomb," am I right? That, and a lot of other interesting information, is contained in "Shakespeare's Tomb," the latest documentary that John reviews at Cult TV Blog.

Pamelyn Ferdin was one of the most ubiquitous child stars on television in the 1960s and 1970s; as David points out at Comfort TV, she was never a regular but appeared in almost every series at one time or another. This week, read about some of her most notable roles.

Robert Clary, the last surviving member of the original cast of Hogan's Heroes (Kenneth Washington, who was in the last season, is still alive) died earlier this week, aged 96. He might be best-known for Hogan, but he was accomplished in many other roles as well. Terence remembers his career at A Shroud of Thoughts.

Did you know that Uncle Sam had a wife? Yes, Aunt Sammy! (The things you learn on the internet.) In 1931 the USDA and Aunt Sammy put out a collection of recipes from her radio program; the Broadcast Archives has her nifty recipe for roast turkey with chestnut stuffing. Just in time for next week! TV

July 26, 2022

A friend, a sitcom, and a museum, or, what I did on my summer vacation

It had been over a year since we'd had anything like a "vacation," which I understand is an extended period of time away from work and home, usually doing something enjoyable; and it had been nearly four years since we'd last done the convention circuit, which I'd started to miss, vaguely. During all that time, the closest we'd come to anything remotely fitting this description was the week we spent last year scouting areas for our move last November, and while that was fun, it was also work. (Paid off, though.)

Clearly, it was time for a change. And while we spent less than 36 hours away from home last weekend, it did include a night in a hotel, so I think that counts. More important than that, it was an occasion to visit an old friend and a new destination. The old friend was Carol Ford, author of Bob Crane: The Definitive Biography, and the new destination was the Liberty Aviation Museum, in Port Clinton, Ohio.

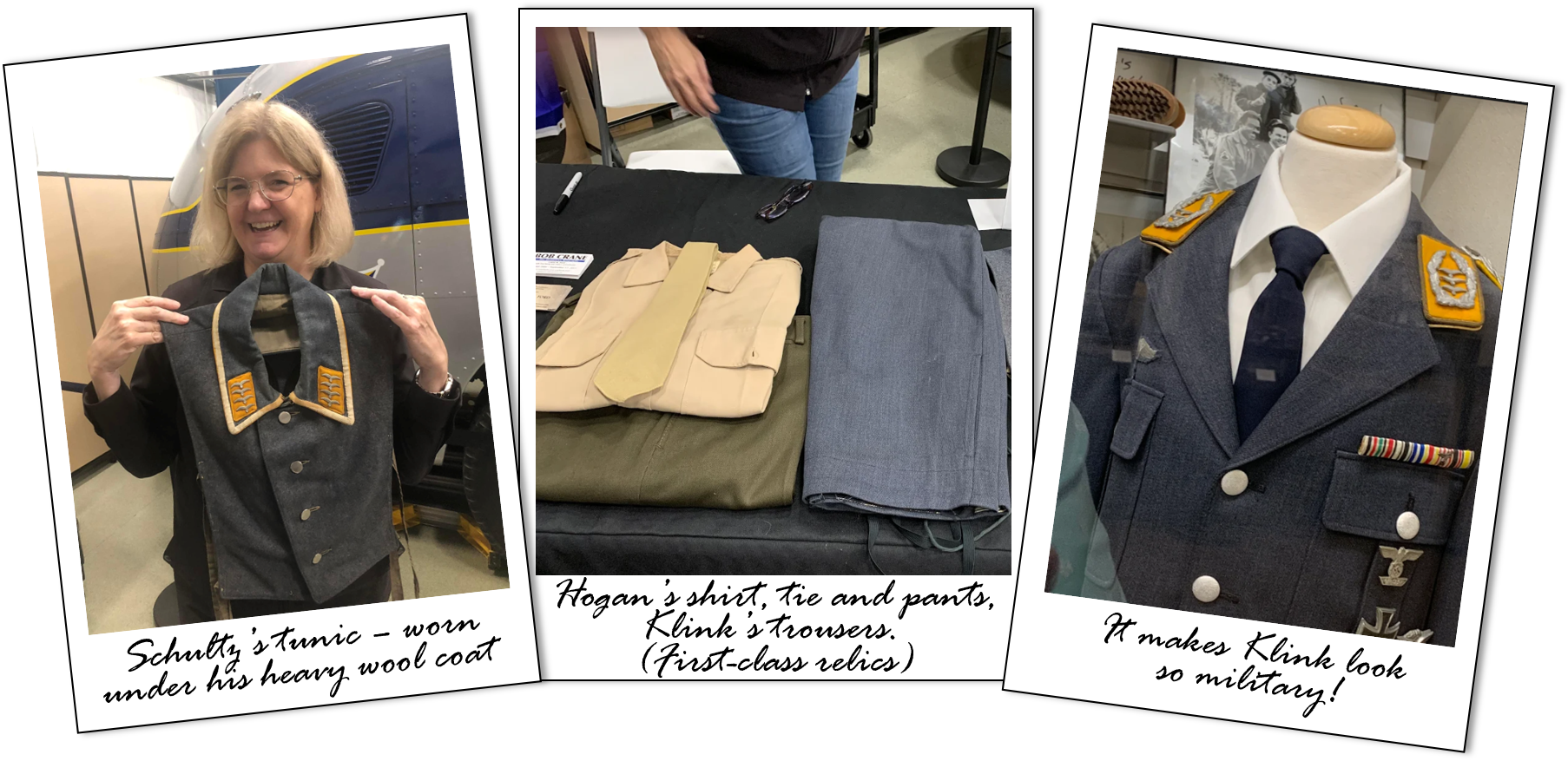

Carol was at the museum for her annual presentation on Bob Crane's life and career. Why Port Clinton, you may ask? Well, as it turns out, the Liberty Aviation Museum has the world's premier collection of Hogan's Heroes memorabilia, a wonderful mixture of artifacts, uniforms, photographs, and other items that would cause any classic television historian, let alone any Hogan fan, to start drooling. (Carefully, though, since if you got anything on Colonel Hogan's shirt or Colonel Klink's pants, Carol would have killed you.) You can learn more about the link between Hogan's Heroes and the Museum here.

We live close enough to the Museum that we could see this display more or less any time, so for us the obvious draw was the chance to get together with Carol for the first time in—well, in almost four years, which is a disgustingly long time to go between visits with a bestie. But then again, there was the virus. I've got Carol's book on Bob Crane (here's my interview with Carol), but it's a pleasure listening to her talk about Bob in front of an inquisitive audience; combine an in-depth knowledge of a subject and a genuine enthusiasm for it, and you have an unbeatable combination. You can get an idea of it from this virtual presentation but trust me—it's much better in person. And while I'm sure someone out there will say I'm biased, my opinions on the book and Carol's presentation are objective. But I am biased; Carol's a sweetheart and a wonderful person and a dear friend, and my wife loves her too. I mean, how much more can one man ask for? And it won't be another four years before we get together again.

In the meantime, the Liberty Aviation Museum is a trip well worth your time, whether you're a Hogan's Heroes fan or not, with historic aircraft, military artifacts—everything aviation from old-time mail routes to modern airliners, and a great, friendly staff as well. I found myself fascinated by things I didn't even know I was interested in, and suddenly I have this great desire to go to YouTube looking for vintage Cleveland air races. It's one thing to find more about what you already know; it's something else to create an interest you didn't have. If that's the test of a great museum, Liberty fits the bill.

Here are more highlights from our weekend living the high life.

TV

May 14, 2021

Around the dial

We'll start this week with a couple of stories from MeTV—first, ths story on how Roy Huggins, creator of Maverick, was forced to change the pilot episode to keep him from collecting any royalties. Having seen my share of WB shows over the past few years, I can vouch for the familiarity of some of these plots—especially the ones written by W. Hermanos.

Next, and perhaps more disturbingly—well, we know that Jack Webb made Pete Kelly's Blues, and was married to Julie London, but does that qualify him to make an album of jazz standards? Be sure to not leave this story before listening to Jack's rendition of "Try a Little Tenderness." No, really.

Last week, you'll recall I linked to Bob Sassone's review of "The 100 Best Sitcoms of All Time" list by Rolling Stone. Well, this week David looks at that same list over at Comfort TV, and has his own thoughts on the subject. Amid the ones they got wrong, David promises they did get some right.

At Bob Crane: Life & Legacy, Carol and Linda introduce their new Hogan's Heroes podcast. It's going on the sidebar, and you should make it part of your regular podcast schedule as well. It's always fun to go behind the scenes, especially at Stalag 13.

Here's another website you might want to look in at from time to time: The Definitive Guide to Murder, She Wrote, with a hat-tip to the Metzinger Sisters over at Silver Scenes.

As you'll recall, we lived in Dallas for a few years, and made it out to the State Fair of Texas most of those years. Therefore, although I prefer the original version of the movie State Fair, I have a soft spot for the Pat Boone-Ann-Margret remake from 1962, because it takes place at that same State Fair. Rick reviews it this week at Classic Film & TV Café. (And yes, Big Tex is still there, even after the fire.

One thing I know for sure is that whenever I visit Cult TV Blog, there's a pretty good chance John's going to introduce me to a series I haven't followed, and this week is no exception. It's "A Case of the Stubborns," an episode from Tales From The Darkside, and it includes an informative comment from our very own Mike Doran! TV

April 9, 2021

Around the dial

It's another two-fer Friday this week, which means we should have twice as many things to look at, right?

Let's begin with this article from Smithsonian Magazine that takes a fond look back at the precursor to today's distance learning: the venerable CBS early-morning series Sunrise Semester. I wonder: if there wasn't any such thing as online education, would television have stepped in with something similar in response to the virus?

At The Twilight Zone Vortex, Jordan takes a closer look at the excellent fifth-season episode In Praise of Pip, which features a wonderfully nuanced performance by Jack Klugman, and includes what is very likely the first mention of American casualties in Vietnam—a script change suggested by deForest Research, after Rod Serling had originally used Laos. Recommended reading, but then you already knew that.

On the latest edition of Flipside: The True Story of Bob Crane (available also at Bob Crane: Life and Legacy, Carol and Linda discuss why, as part of "Becoming Colonel Hogan," Bob had such a lousy German accent. The answer, as they say, may surprise you.

I suppose I'm more "Yesterday" than "Tomorrow," but that doesn't stop me from appreciating the latest at Cult TV Blog: John's write-up of the Brit series The Tomorrow People; "In various places it is definitely stonking good television, but in others represents the worst of 1970s TV." Find out what he thinks of the 1975 series "Secret Weapon."

Hey, how about another British show? This time, it's the return of British TV Detectives, and Rick's review of the ongoing detective show The Bay, starring Morven Christie) as a family liaison officer struggling to balance turmoil both on the job and at home. Glad to see this blog back!

Let's stay with the British theme for a moment more, as RealWeegieMidget Reviews looks at 2003's "The Wife of Bath," which Gill describes as "A Sexed-up Modern Day Adaptation of one of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales" with Julie Walters, Paul Nicholls and Bill Nighy. Seeing as how Chaucer was already fairly bawdy, you can imagine what happens here.

Two from Comfort TV: first, David takes the measure of IMDb's "top rated classic TV episodes," and asks if we agree. (No, although there are a couple of perceptive choices.) To cleanse the palate, so to speak, there's also the twelve most memorable commercials featuring classic TV stars, and that's a much easier sell.

The latest edition of the Hitchcock Project at bare-bones e-zine has Jack looking at the 1959 episode "No Pain," a nasty little piece written by William Fay and starring Brian Keith and Joanna Moore as an unhappily married couple, one of whom has a surprise in store for the other. . .

"Oh, what the heck: here's another British show to end on. At Drunk TV, it's a look at the BBC's 1966 "nightmarish" version of Alice in Wonderland, directed by Jonathan Miller, and featuring an all-star cast including Peter Sellers, Sir John Gielgud, Sir Michael Redgrave, Wilfrid Brambell, Peter Cook, Alan Bennett, John Bird, Leo McKern, and newcomer Anne-Marie Mallik as Alice.

There—I think we proved the adage "double your pleasure, double your fun," don't you? TV

December 16, 2020

Hogan's Heroes - the final episode

Idon't think I've ever given an old piece a bump to the top; to be sure, I've resussitated a few old pieces here and there, if they prove to be timely in their subject matter (or if I prove to be untimely in my ability to come up with something new), but usually once I write something, it becomes part of the archives, destined to be found only by people looking for it (or stumbling upon it). Today, though, I make an exception.

A few years ago—almost nine now, if you can believe it—I wrote what I thought was a fanciful little piece speculating on what would have happened if one of my favorite shows, Hogan's Heroes, had been given a final episode. Today, of course, it would go without saying; just about any series that isn't cancelled in the middle of its first season gets the chance to have the last word. Back then, though, that generally wasn't the case. But if there were ever a series that deserved a closing episode, it's Hogan. After all, the concept is a closed circuit; we all know that World War II ended, and so the heroes' time in Stalag 13 would have come to an end as well. Additionally, there's the unique dymanic of the relationship between the captors and captives, especially that between Hogan and Klink, that really begs a "rest of the story" story. And, being a comedy, we can be pretty sure that it won't be a tragic end that befalls these much-loved characters.

Over the years, this post has continued to get comments; two, in fact, in the last couple of weeks. I have no other essay that can make that claim, which I think speaks less to my skill as a writer and more to the enduring popularity of Hogan's Heroes. However, because it was originally published so long ago, it occurs to me that very few of you have had the chance to see this continuing discussion in the combox. Therefore, for your pleasure, as well as that of those who'd like to offer their own scenario on how Hogan's Heroes ends, I thought I'd bump it back to the top. And so, we return to February 21, 2012, and an episode that never was.

t t t

I've never been embarrassed to admit that Hogan's Heroes was, and remains, one of my all-time favorites. It was the first series I got in its entirety on DVD; the acting was superb, the writing spot-on, the plots often literate and clever and frequently downright hilarious. The cast—Bob Crane as Hogan, Werner Klemperer as Klink, John Banner as Schultz, Klink’s nemeses General Burkhalter and Major Hochstetter (Leon Askin and Howard Caine) and the whole cast of heroes (Robert Clary, Richard Dawson, Ivan Dixon,* Larry Hovis, and Kenneth Washington)—were uniformly great.

*Ivan Dixon—Sergeant Kinchloe, Colonel Hogan's chief of staff, whom Hogan would almost certainly have taken with him wherever he went—was, as loyal reader Fred Baillargeron points out, was the first black television actor to receive "equal-billing" in a show's credits.

The last episode, airing on July 4, 1971 could have been any particular episode from that final season, and in fact there’s no reason to think it was conceived any other way. A seventh season had been expected, and so the show's cancellation came as something of a surprise, but, in fact, it had been around for six years and, like most extended-run shows, was beginning to show its age, and the ratings had begun to fade. In other words, a perfect candidate for a wrap-up episode.

So what would that final episode have been like? Well, many of the major events of the war had come and gone during Hogan’s run (though not necessarily in linear order) including D-Day. The Allies might have come to liberate the camp, or they might simply have terminated Hogan’s assignment (the POWs, you recall, were stationed at Stalag 13, posing as prisoners but in reality operating a massive underground commando and espionage ring). Myself, I prefer to think of the series concluding with the end of the war; Burkhalter and Hochstetter, being true believers in the Nazi regime, probably would have been taken prisoner themselves by the Allies. (In reality, they might have committed suicide, but let’s not make this too realistic.)

Hogan and his men probably would have vouched for Schultz, who really was just a working man at a job he didn’t particularly like, and possibly even Klink, who when all was said and done didn’t really bear the POWs any real malice; he was too incompetent to have done too much harm. The men would have been lauded as true heroes for their daring behind-the-lines escapades, none more so than Colonel Robert Hogan himself. Already a full colonel, it’s reasonable to assume that Hogan would have come out of the war at least a Brigadier General, with a brilliant future should he decide to stay in the service. The Army, recognizing what it had on its hands, would have made the most of the photogenic, dynamic Hogan. (An earlier episode had actually involved the brass bringing Hogan back home, cashing in on his accomplishments by having him lead bond drives throughout the country.)

And where do things go from there? There certainly would have been a book about such an audacious assignment, just as there was with A Bridge Too Far, A Man Called Intrepid, The Great Escape and other true war stories, probably called, simply, Hogan’s Heroes, by General Robert Hogan as told to David Halberstam. In due course, a movie would have been made based on the book, and it’s fun to speculate on who would have played Hogan in the movie. (Greg Kinnear, anyone? Probably more likely Kirk Douglas.) Hogan might have served in Korea, flying the same kinds of bomber missions he flew in Europe during WWII; on the other hand, he probably would have already been back in Washington, with a high-level job in the Pentagon.

Come the early 60s, Hogan would still have been only about 50. JFK, who also recognized talent when he saw it, might have made Hogan his Air Force aide, working directly out of the White House. (I'll bet they would have had some adventures together.) Our co-blogger Steve suggests that Hogan might have been in charge of the Bay of Pigs invasion, which would have meant that the fiasco would have been averted, Castro toppled, and Cuba liberated. Without Castro and the CIA working behind the scenes, JFK doesn’t meet his death at the hands of conspirators in Dallas, and as we all know that means no expanded war in Vietnam. (Yeah, right.)

See how easy this is? The world as we know it changes completely! Kennedy goes through with his plan to dump LBJ from the ticket in 1964, choosing instead the charismatic Senator from Minnesota, Hubert Humphrey. Bobby lives, not being shot in the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, because it is JFK’s loyal Vice President Humphrey who becomes the unanimous choice to continue the legacy of the New Frontier. (Bobby continues as Senator from New York, even providing consultation with that young Clinton fellow from Arkansas who’d had his picture taken with JFK that time. Bobby and Bill fly to Hollywood often and hang out with friends.

The Republicans, of course, turn to Richard Nixon as the best bet to unseat Humphrey and end eight years of Democratic dominance. In a peaceful campaign prosperity becomes the number one issue, and the voters decide to give the Republicans and their tax breaks a chance, electing Nixon as president. True to form, Nixon immediately sees an opportunity to wreak havoc on his enemies, even authorizing a burglary at Democratic headquarters at the Watergate. (What was that about history changing?) The country in a shambles, being led by the president who pardoned the man responsible for it, the people turn to someone they can trust: Robert Hogan, the now-retired military hero, the man who has always stayed above politics, the most trusted man in America (next to Walter Cronkite). And with him, the charismatic former actor and governor of California, Ronald Reagan. What a match! Hogan and Reagan – or is it Reagan and Hogan? Whatever. Happy days are here again.

All that from a simple half-hour sitcom. See why it’s so important for series to have final episodes? You can never tell how history could turn out differently. TV

March 20, 2020

Around the dial

If you're like the folks in the picture above—and does anyone actually dress like that to watch television?—you've found yourself all cooped up, with no place to go. Fear not: our courageous bloggers are on hand to take your minds off the present difficulties.

Let's start at Comfort TV, where David gives us a list of shows that can help us pass the time while in quarantine. His first choice, Gunsmoke, is capable of doing it alone; in case we've forgotten, there are 635 episodes to go through, and they'll all be available on DVD.

"Lie to the kid!" sounds like a strange piece of advice, but in the context of this Hogan's Heroes episode, it's a perfect example of why everything you do during this time is important. It's a good reminder from Carol at Bob Crane: Life & Legacy.

Reading is a perfect way to pass some unexpected free time (or any time, for that matter), and at The Twilight Zone Vortex, Jordan presents the first in a series of stories that will be appearing every other Wednesday, direct from the pages of the 1960s Twilight Zone comic book. (Of course, if you're looking for even more reading material, feel free to check these out!)

At Classic Film & TV Cafe, Rick brings us the 1973 CBS made-for-TV movie Birds of Prey, a chase film using helicopters, starring David Janssen as a traffic pilot in pursuit of bank robbers with a hostage. It's well above the standard fare, with Janssen terrific as the world-weary pilot,

Television's New Frontier: the 1960s takes us to 1961, and the 1961 portion of the sixth season of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Along with an overview of the episodes, we're given an extended, and excellent, look at Hitch's philosophy, and how he managed to get away with so much on TV.

We've had two more of television's past stars pass away in the past week, and at A Shroud of Thoughts, Terence has his usual thoughtful remembrances of each: Lyle Waggoner, an underrated part of Carol Burnett's troupe (and co-star of Wonder Woman; you might have noticed him if your attention wasn't distracted); and Stuart Whitman, star of Cimarron Strip, Oscar nominee for Best Actor in The Mark, and a familiar face from many a television show. They both will be missed.

There's plenty more to look at and watch on the sidebar, so be sure and make good use of it. It won't end our involuntary confinement, but it might help the time go a little faster. TV

Let's start at Comfort TV, where David gives us a list of shows that can help us pass the time while in quarantine. His first choice, Gunsmoke, is capable of doing it alone; in case we've forgotten, there are 635 episodes to go through, and they'll all be available on DVD.

"Lie to the kid!" sounds like a strange piece of advice, but in the context of this Hogan's Heroes episode, it's a perfect example of why everything you do during this time is important. It's a good reminder from Carol at Bob Crane: Life & Legacy.

Reading is a perfect way to pass some unexpected free time (or any time, for that matter), and at The Twilight Zone Vortex, Jordan presents the first in a series of stories that will be appearing every other Wednesday, direct from the pages of the 1960s Twilight Zone comic book. (Of course, if you're looking for even more reading material, feel free to check these out!)

At Classic Film & TV Cafe, Rick brings us the 1973 CBS made-for-TV movie Birds of Prey, a chase film using helicopters, starring David Janssen as a traffic pilot in pursuit of bank robbers with a hostage. It's well above the standard fare, with Janssen terrific as the world-weary pilot,

Television's New Frontier: the 1960s takes us to 1961, and the 1961 portion of the sixth season of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Along with an overview of the episodes, we're given an extended, and excellent, look at Hitch's philosophy, and how he managed to get away with so much on TV.

We've had two more of television's past stars pass away in the past week, and at A Shroud of Thoughts, Terence has his usual thoughtful remembrances of each: Lyle Waggoner, an underrated part of Carol Burnett's troupe (and co-star of Wonder Woman; you might have noticed him if your attention wasn't distracted); and Stuart Whitman, star of Cimarron Strip, Oscar nominee for Best Actor in The Mark, and a familiar face from many a television show. They both will be missed.

There's plenty more to look at and watch on the sidebar, so be sure and make good use of it. It won't end our involuntary confinement, but it might help the time go a little faster. TV

April 10, 2019

What Hogan's Heroes (and other WWII television series) can tell us about wartime military ethics

When you’ve seen every episode of Hogan’s Heroes as often as I have, you’re allowed to let your mind wander a bit. By this time, you can identify each episode within the first ten seconds, you can quote an alarming amount of dialog, you know all of Hogan’s scams and how Klink reacts to them, you know that through it all, Schultz never sees anything. It’s all as comforting as a warm blanket in the middle of winter.

So when you’ve seen, say, “Information Please” for the tenth time, you start to pay more attention to the little things, like when Hogan decides the only way to get rid of the German officer threatening their operations is to frame him as a traitor, and Newkirk, after listening to the plan, comments that “We really are a nasty lot, we are.” And “The Assassin,” when, after discovering that a Nazi scientist is in camp working on atomic research, Hogan declares, “We got to kill him,” to which a startled Carter replies, “Just doesn’t sound like us, Colonel.” And “Hot Money,” which involves the Nazis setting up a counterfeiting operation, in which the lead scientist of the operation voices concern over the morality of counterfeiting even during wartime.

These represent some of the rare moments of genuine self-reflection in the series, when, even amid the absurdist humor, the characters dwell on the implications of their actions with an acute awareness of the consequences involved. Setting aside the fact that we’re talking about fictional people in a very improbable setting, you have to ask—what does it all really mean? The storylines in Hogan’s Heroes encompass a wide range of acts, including deception, misinformation, lying, and killing. How does one assess their morality during wartime? After all, just because we’re talking about a comedy, that doesn’t mean truth can’t be found somewhere in the midst. And not just Hogan's Heroes, of course, but other wartime television series as well.

To find the answers to these questions, I decided what I needed was an expert. So I went out and got one.

Dr. Robert G. Kennedy is a Professor of Catholic Studies at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, and his area of expertise includes St. Thomas Aquinas, who did quite a lot of writing about the Catholic theory on Just War. Among other things, he’s presented on topics such as “A Catholic Analysis of Modern Problems for the Just War Tradition,” “Is the Just War Theory Obsolete?” and “Is the Doctrine of Preemption a Legitimate Element of the Just War Tradition?” With credentials like this, I figured he was the person I was looking for. He also knows something about military ethics as portrayed in television and the movies, which made it less likely he’d think I was completely around the bend. “It’s interesting, the questions that a 50-year-old sitcom can prompt,” he said after I’d described what was on my mind; then, as a true scholar and gentleman, he gave serious consideration to my questions and rose to the challenge.

“The Catholic tradition since Augustine has held that lying—deliberately asserting to someone as true something that you know to be false—is always wrong. The key word here is asserting.” For example, things such as acting in a theatrical performance, telling a joke, and so on, are in many cases not assertions; consequently, false statements on those cases are not lies. (Philosophers often debate where to draw lines, but that’s a question for another day.)

Addressing the question in “Information, Please,” in which the boys frame a German officer, Major Kohler, by falsely implicating him as a traitor, Dr. Kennedy continued. “If Hogan makes a false assertion, he is lying and acting wrongly, even if the end to be achieved is worthwhile. On the other hand, if memory serves, the story line in these matters often involved deception (lying is a species of deception, but not all deception is wrong). Suppose Hogan ‘carelessly’ leaves a forged document someplace where Klink will find it, and Klink immediately draws a conclusion, as he was meant to do, that some officer or another is a traitor”—a fairly common occurrence in the show. “Or suppose Hogan, in conversation with Klink, asks a number of insinuating questions, planting the idea in Klink’s mind that the officer is a suspicious character.

“In neither of these cases does Hogan assert anything, even though he certainly means Klink (and others) to draw conclusions that are false but helpful to Hogan’s aims. In cases like this he has certainly engaged in deception, but he has not lied. Not all deception is morally sound, but in some of these cases it might be.” He added, however, that deception intended to cause an innocent person to be harmed, even if it might not be lying, may still very well be immoral, a concern which Newkirk seems to be alluding to in his comments.

By now, I was beginning to understand why I’d wanted an expert.

In the episode “How to Win Friends and Influence Nazis,” Hogan’s assignment is to convince Dr. Karl Svenson, a world-famous Swedish chemist working on a formula for a new steel alloy, not to give the formula to the Nazis. Failing that, his mission is to assassinate Svenson, which he’s prepared to do with a small bomb implanted in a pen. To understand the morality of such an action, it’s important to make a distinction—not between military and civilian personnel, as is sometimes supposed, but between combatants and non-combatants. “Some persons in uniform are generally held to be non-combatants, such as chaplains, medics, and perhaps even the JAG corps. But even here, the instant a medic or chaplain picks up a weapon, he becomes a combatant—which is why we generally have very strict rules against these people ever engaging in actual combat. The moment they do so, they contaminate the immunity of all other medics and chaplains. They can say a prayer but they can’t pass the ammunition.

“Strictly speaking, combatants are liable to attack, even lethal attack, even when they are not actually engaged, at that moment, in combat operations. The argument would be that they are still ongoing participants in the wrongful project of the enemy and therefore may be subject to the force necessary to impede their project. An air base, for example, is a legitimate military target, even at night when the personnel are asleep. But there are limits. Injured soldiers in a hospital are likely not combatants, soldiers on leave back home, even when wearing a uniform, are likely not combatants, and so on. In all this, by the way, there is the assumption that it is the enemy who is engaged in a wrongful project, not our own side. We also assume, while acknowledging that this is hard to measure, that the level of force applied should not exceed what is necessary to impede the wrongful project. So, we should not kill enemy soldiers if we can disable them; we should not disable them, if we can persuade them to surrender.”

In the case of Dr. Svenson, “though a civilian, [he] is likely a combatant, even if a reluctant one. Even though he is not in uniform, he is engaged critically, if at some remove, in developing weapon components that could be strategically effective against his nation’s opponents”—such action means “he is directly participating in the wrongful project of the Germans and therefore enabling in a proximate way their combat operations.* Is he a legitimate target? Again, there are extremes but here we can talk about the distinction between pre-emptive action and preventive action. Pre-emptive action, which is often justified, seeks to neutralize an imminent threat. Preventive action seeks to neutralize a threat that one can imagine becoming real at some point in the future, but which poses no imminent danger. It is hard to imagine a situation in which preventive action can be justified.

*An analysis that could apply to “The Assassin” as well.

“So, what is the situation with [Svenson]? Is he on his way to deliver the formula for the new alloy to the Nazis or is he merely making progress on developing the formula, and might reasonably succeed, in a month, or a year or two? I would say that if he has the formula and is about to give it to the Nazis, then he probably poses an imminent threat and could be a legitimate target. But probably not if he is merely making progress. We would also want to know how important his formula really is and what other means might be available to prevent the exchange. The answers would address the issue of proportionality.” In this case, Svenson tells Hogan that work on the formula will require “two or three month’s more work,” to which Hogan replies, “I’ve now got time to convince you to come over to my side.” The implication is that Hogan is prepared to do whatever it takes to make killing Svenson a last resort; it’s a wise—and moral—judgment.

Then there’s an episode like “The Swing Shift,” in which the men infiltrate industrialist Hans Speer’s cannon-making factory, so they can sabotage the plant with explosives? Assessing this situation requires “sound judgment and attention to details and context,” according to Dr. Kennedy; while extreme situations are often easy to resolve, “the closer they are, in fact, to the middle, the less clear they become.” Given that factory workers are not automatically considered combatants, any attack, if possible, should be staged when the workers are not working. In “The Swing Shift,” however, the plan is for the factory to operate around the clock. What then?

Dr. Kennedy compares this example to the bombing of the famous ball bearing plant at Schweinfurt* “Ball-bearing manufacture was a choke point in the German war industry, as so many pieces of equipment required ball bearings. Destroy the plant and war production would be crippled. It had very high strategic value, not merely a tactical value. A strong argument can be made that harm to the workers was justified by that strategic value.”

*Ironically, in the episode Hogan’s request to London for an air strike is tabled due to higher-priority targets, among which is—the real-life ball-bearing plant at Schweinfurt. It’s not the first time the writers got little details like this correct, and quite possibly the mention of Schweinfurt was designed specifically to justify the sabotage to Herr Speer’s factory (whose name, of course, is an indirect reference to Nazi Armaments Minister Albert Speer).

Overall, these kinds of actions call for careful consideration. Examples of non-uniformed combatants could include “a civilian truck driver delivering ammunition to troops in battle or of a technical advisor helping combat troops to operate complex equipment, and so on.” However, Dr. Kennedy adds, “I am less inclined to say [that factory workers are combatants] in general. One issue here would have to do with what it is they are making? Is it bullets and cannon shells or army boots? Are they building ships or canning vegetables? We usually draw some lines with respect to the proximity of the support provided—the mother knitting socks for her soldier son is not a combatant—and whether the support itself is neutral (that is, not combat specific). In the latter case, we would likely say that the truck driver delivering groceries to a military base is not a combatant since this would be done without regard to war or peace.

“A second issue has to do with timing. Factories don’t move and in principle, therefore, they could be attacked when the workers are not working. In the Second World War, the British bombed Germany at night, when they could not see the target. Their reasoning was that it didn’t matter whether they hit the factory or the workers’ homes: production would stop either way. But Catholics would think that there is a very important difference here.

“A principle of proportionality has to be introduced: is the military objective sufficiently important to justify a certain level of genuinely unintended casualties? One test question is to ask whether we would proceed with an operation if we were bombing (let’s say) one of our own cities that had been occupied by the enemy, and the unintended casualties would be our own citizens. We are on more solid grounds if we could answer affirmatively, as the French did with respect to the bombing of their own railyards immediately before D-Day. At the other extreme, was the bombing of Japanese and German cities in the latter days of the war, when our objective was clearly to use the deaths of non-combatants as leverage to force surrender.”

In summary, says Dr. Kennedy, “war is a very messy business. It always involves unintended casualties and collateral damage. Cases like these, and there are a great many, irritate people who want formal rules for all occasions. There are no such rules, which is why prudence is the preeminent practical virtue. And in the difficult cases, the decision maker often lacks some vital piece of information, so in the end we often do the best we can. Here again, the genuinely virtuous person, who will be less swayed by bias or emotion, is more likely to judge well.”

By this time I was thoroughly exhausted, but also exhilarated and intellectually stimulated. I thanked Dr. Kennedy not only for his time, but his patience in answering what some people might consider silly questions that read far too much into light entertainment. Looking back on the discussion, it seemed to have justified my decades-long fandom of Hogan’s Heroes (which I think does very well when it comes to ethical choices). More important, it provides us something to think about whenever we watch depictions of war on television (or in the movies)—not to the exclusion of the program’s entertainment value, but rather in amplification of it, complimenting and enhancing our understanding of what we watch. Furthermore, the same questions can be asked of other kinds of shows: police procedurals, for example, or mysteries. It doesn’t matter whether it’s the most searing drama or the silliest comedy—they all play using the same set of moral rules, even if they don’t abide by them.

War forces terrible choices on everyone: not just the combatants, but those who issue the orders sending them into battle, the politicians responsible for making policy, the civilians providing support to their armed forces. We live with the consequences of our choices, and someday we answer for them. How right Robert E. Lee was, when he observed that “It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it.” TV

A special thanks to my friend Dr. David Deavel for providing the introduction to Dr. Robert Kennedy.

So when you’ve seen, say, “Information Please” for the tenth time, you start to pay more attention to the little things, like when Hogan decides the only way to get rid of the German officer threatening their operations is to frame him as a traitor, and Newkirk, after listening to the plan, comments that “We really are a nasty lot, we are.” And “The Assassin,” when, after discovering that a Nazi scientist is in camp working on atomic research, Hogan declares, “We got to kill him,” to which a startled Carter replies, “Just doesn’t sound like us, Colonel.” And “Hot Money,” which involves the Nazis setting up a counterfeiting operation, in which the lead scientist of the operation voices concern over the morality of counterfeiting even during wartime.

These represent some of the rare moments of genuine self-reflection in the series, when, even amid the absurdist humor, the characters dwell on the implications of their actions with an acute awareness of the consequences involved. Setting aside the fact that we’re talking about fictional people in a very improbable setting, you have to ask—what does it all really mean? The storylines in Hogan’s Heroes encompass a wide range of acts, including deception, misinformation, lying, and killing. How does one assess their morality during wartime? After all, just because we’re talking about a comedy, that doesn’t mean truth can’t be found somewhere in the midst. And not just Hogan's Heroes, of course, but other wartime television series as well.

To find the answers to these questions, I decided what I needed was an expert. So I went out and got one.

Dr. Robert G. Kennedy is a Professor of Catholic Studies at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, and his area of expertise includes St. Thomas Aquinas, who did quite a lot of writing about the Catholic theory on Just War. Among other things, he’s presented on topics such as “A Catholic Analysis of Modern Problems for the Just War Tradition,” “Is the Just War Theory Obsolete?” and “Is the Doctrine of Preemption a Legitimate Element of the Just War Tradition?” With credentials like this, I figured he was the person I was looking for. He also knows something about military ethics as portrayed in television and the movies, which made it less likely he’d think I was completely around the bend. “It’s interesting, the questions that a 50-year-old sitcom can prompt,” he said after I’d described what was on my mind; then, as a true scholar and gentleman, he gave serious consideration to my questions and rose to the challenge.

“The Catholic tradition since Augustine has held that lying—deliberately asserting to someone as true something that you know to be false—is always wrong. The key word here is asserting.” For example, things such as acting in a theatrical performance, telling a joke, and so on, are in many cases not assertions; consequently, false statements on those cases are not lies. (Philosophers often debate where to draw lines, but that’s a question for another day.)

Addressing the question in “Information, Please,” in which the boys frame a German officer, Major Kohler, by falsely implicating him as a traitor, Dr. Kennedy continued. “If Hogan makes a false assertion, he is lying and acting wrongly, even if the end to be achieved is worthwhile. On the other hand, if memory serves, the story line in these matters often involved deception (lying is a species of deception, but not all deception is wrong). Suppose Hogan ‘carelessly’ leaves a forged document someplace where Klink will find it, and Klink immediately draws a conclusion, as he was meant to do, that some officer or another is a traitor”—a fairly common occurrence in the show. “Or suppose Hogan, in conversation with Klink, asks a number of insinuating questions, planting the idea in Klink’s mind that the officer is a suspicious character.

“In neither of these cases does Hogan assert anything, even though he certainly means Klink (and others) to draw conclusions that are false but helpful to Hogan’s aims. In cases like this he has certainly engaged in deception, but he has not lied. Not all deception is morally sound, but in some of these cases it might be.” He added, however, that deception intended to cause an innocent person to be harmed, even if it might not be lying, may still very well be immoral, a concern which Newkirk seems to be alluding to in his comments.

By now, I was beginning to understand why I’d wanted an expert.

In the episode “How to Win Friends and Influence Nazis,” Hogan’s assignment is to convince Dr. Karl Svenson, a world-famous Swedish chemist working on a formula for a new steel alloy, not to give the formula to the Nazis. Failing that, his mission is to assassinate Svenson, which he’s prepared to do with a small bomb implanted in a pen. To understand the morality of such an action, it’s important to make a distinction—not between military and civilian personnel, as is sometimes supposed, but between combatants and non-combatants. “Some persons in uniform are generally held to be non-combatants, such as chaplains, medics, and perhaps even the JAG corps. But even here, the instant a medic or chaplain picks up a weapon, he becomes a combatant—which is why we generally have very strict rules against these people ever engaging in actual combat. The moment they do so, they contaminate the immunity of all other medics and chaplains. They can say a prayer but they can’t pass the ammunition.

“Strictly speaking, combatants are liable to attack, even lethal attack, even when they are not actually engaged, at that moment, in combat operations. The argument would be that they are still ongoing participants in the wrongful project of the enemy and therefore may be subject to the force necessary to impede their project. An air base, for example, is a legitimate military target, even at night when the personnel are asleep. But there are limits. Injured soldiers in a hospital are likely not combatants, soldiers on leave back home, even when wearing a uniform, are likely not combatants, and so on. In all this, by the way, there is the assumption that it is the enemy who is engaged in a wrongful project, not our own side. We also assume, while acknowledging that this is hard to measure, that the level of force applied should not exceed what is necessary to impede the wrongful project. So, we should not kill enemy soldiers if we can disable them; we should not disable them, if we can persuade them to surrender.”

In the case of Dr. Svenson, “though a civilian, [he] is likely a combatant, even if a reluctant one. Even though he is not in uniform, he is engaged critically, if at some remove, in developing weapon components that could be strategically effective against his nation’s opponents”—such action means “he is directly participating in the wrongful project of the Germans and therefore enabling in a proximate way their combat operations.* Is he a legitimate target? Again, there are extremes but here we can talk about the distinction between pre-emptive action and preventive action. Pre-emptive action, which is often justified, seeks to neutralize an imminent threat. Preventive action seeks to neutralize a threat that one can imagine becoming real at some point in the future, but which poses no imminent danger. It is hard to imagine a situation in which preventive action can be justified.

*An analysis that could apply to “The Assassin” as well.

“So, what is the situation with [Svenson]? Is he on his way to deliver the formula for the new alloy to the Nazis or is he merely making progress on developing the formula, and might reasonably succeed, in a month, or a year or two? I would say that if he has the formula and is about to give it to the Nazis, then he probably poses an imminent threat and could be a legitimate target. But probably not if he is merely making progress. We would also want to know how important his formula really is and what other means might be available to prevent the exchange. The answers would address the issue of proportionality.” In this case, Svenson tells Hogan that work on the formula will require “two or three month’s more work,” to which Hogan replies, “I’ve now got time to convince you to come over to my side.” The implication is that Hogan is prepared to do whatever it takes to make killing Svenson a last resort; it’s a wise—and moral—judgment.

Then there’s an episode like “The Swing Shift,” in which the men infiltrate industrialist Hans Speer’s cannon-making factory, so they can sabotage the plant with explosives? Assessing this situation requires “sound judgment and attention to details and context,” according to Dr. Kennedy; while extreme situations are often easy to resolve, “the closer they are, in fact, to the middle, the less clear they become.” Given that factory workers are not automatically considered combatants, any attack, if possible, should be staged when the workers are not working. In “The Swing Shift,” however, the plan is for the factory to operate around the clock. What then?

Dr. Kennedy compares this example to the bombing of the famous ball bearing plant at Schweinfurt* “Ball-bearing manufacture was a choke point in the German war industry, as so many pieces of equipment required ball bearings. Destroy the plant and war production would be crippled. It had very high strategic value, not merely a tactical value. A strong argument can be made that harm to the workers was justified by that strategic value.”

*Ironically, in the episode Hogan’s request to London for an air strike is tabled due to higher-priority targets, among which is—the real-life ball-bearing plant at Schweinfurt. It’s not the first time the writers got little details like this correct, and quite possibly the mention of Schweinfurt was designed specifically to justify the sabotage to Herr Speer’s factory (whose name, of course, is an indirect reference to Nazi Armaments Minister Albert Speer).

Overall, these kinds of actions call for careful consideration. Examples of non-uniformed combatants could include “a civilian truck driver delivering ammunition to troops in battle or of a technical advisor helping combat troops to operate complex equipment, and so on.” However, Dr. Kennedy adds, “I am less inclined to say [that factory workers are combatants] in general. One issue here would have to do with what it is they are making? Is it bullets and cannon shells or army boots? Are they building ships or canning vegetables? We usually draw some lines with respect to the proximity of the support provided—the mother knitting socks for her soldier son is not a combatant—and whether the support itself is neutral (that is, not combat specific). In the latter case, we would likely say that the truck driver delivering groceries to a military base is not a combatant since this would be done without regard to war or peace.

“A second issue has to do with timing. Factories don’t move and in principle, therefore, they could be attacked when the workers are not working. In the Second World War, the British bombed Germany at night, when they could not see the target. Their reasoning was that it didn’t matter whether they hit the factory or the workers’ homes: production would stop either way. But Catholics would think that there is a very important difference here.

“A principle of proportionality has to be introduced: is the military objective sufficiently important to justify a certain level of genuinely unintended casualties? One test question is to ask whether we would proceed with an operation if we were bombing (let’s say) one of our own cities that had been occupied by the enemy, and the unintended casualties would be our own citizens. We are on more solid grounds if we could answer affirmatively, as the French did with respect to the bombing of their own railyards immediately before D-Day. At the other extreme, was the bombing of Japanese and German cities in the latter days of the war, when our objective was clearly to use the deaths of non-combatants as leverage to force surrender.”

In summary, says Dr. Kennedy, “war is a very messy business. It always involves unintended casualties and collateral damage. Cases like these, and there are a great many, irritate people who want formal rules for all occasions. There are no such rules, which is why prudence is the preeminent practical virtue. And in the difficult cases, the decision maker often lacks some vital piece of information, so in the end we often do the best we can. Here again, the genuinely virtuous person, who will be less swayed by bias or emotion, is more likely to judge well.”

By this time I was thoroughly exhausted, but also exhilarated and intellectually stimulated. I thanked Dr. Kennedy not only for his time, but his patience in answering what some people might consider silly questions that read far too much into light entertainment. Looking back on the discussion, it seemed to have justified my decades-long fandom of Hogan’s Heroes (which I think does very well when it comes to ethical choices). More important, it provides us something to think about whenever we watch depictions of war on television (or in the movies)—not to the exclusion of the program’s entertainment value, but rather in amplification of it, complimenting and enhancing our understanding of what we watch. Furthermore, the same questions can be asked of other kinds of shows: police procedurals, for example, or mysteries. It doesn’t matter whether it’s the most searing drama or the silliest comedy—they all play using the same set of moral rules, even if they don’t abide by them.

War forces terrible choices on everyone: not just the combatants, but those who issue the orders sending them into battle, the politicians responsible for making policy, the civilians providing support to their armed forces. We live with the consequences of our choices, and someday we answer for them. How right Robert E. Lee was, when he observed that “It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it.” TV

A special thanks to my friend Dr. David Deavel for providing the introduction to Dr. Robert Kennedy.

January 4, 2019

Around the dial

For the first Hitchcock Project of the year, Jack at bare-bones e-zine wraps up his overview of Bernard C. Schoenfeld's work with season five's "Hitch Hike" (which I haven't seen yet, so I'm not going to go to far with it). Schoenfeld strikes me as one of the program's best writers.

The Broadcast Archives at the University of Maryland shares a 1967 ad from Saginaw's WNEM thanking women viewers for making their movies and syndicated programs so successful. They call the ad "patronizing," and perhaps it is; or perhaps it's a fairly accurate assessment of the way things were then, as well as an example of how things have changed in the intervening 52 years.

We haven't heard from Amanda lately, but the "Queen of TV Movie Knowledge" is back at Made for TV Mayhem with this review of "The Scarecrow," which appeared on PBS's excellent Hollywood Television Theater back in 1972. A pity that even PBS doesn't have room for plays like this anymore.

At Bob Crane: Life & Legacy, Carol travels (visually) to Port Clinton, Ohio, home of the Liberty Aviation Museum, repository of the Hogan's Heroes uniforms and props, for a big band version of the "Hogan's Heroes March."

Jodie takes a look back at 2018 at Garroway at Large, along with an update on her Dave Garroway biography. I can't wait to read this; Jodie says she's beginning to understand Garroway, and that should be fascinating.

Martin Grams tells us how we can help save Popeye the Sailor. It has to do with Warners' release of volume four of the Popeye cartoons, which starts in on the 1940s. As seems to be the way of things nowadays, Warners says there will only be additional volumes released if the sales volume demands it. Popeye fans, you know what to do.

Take a listen to the latest edition of TV Confidential; film and television actor Kirk Bovill and television historian Steve Randisi will join Ed Robertson this weekend for a brand new edition , airing January 4-6. Follow the link to find out where and when you can listen.

And by the way, as I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I'm on Twitter now, so be sure to follow me for treats not available on the website. Speaking of which, there'll be another TV Guide on the website tomorrow; come back then. TV

The Broadcast Archives at the University of Maryland shares a 1967 ad from Saginaw's WNEM thanking women viewers for making their movies and syndicated programs so successful. They call the ad "patronizing," and perhaps it is; or perhaps it's a fairly accurate assessment of the way things were then, as well as an example of how things have changed in the intervening 52 years.

We haven't heard from Amanda lately, but the "Queen of TV Movie Knowledge" is back at Made for TV Mayhem with this review of "The Scarecrow," which appeared on PBS's excellent Hollywood Television Theater back in 1972. A pity that even PBS doesn't have room for plays like this anymore.

At Bob Crane: Life & Legacy, Carol travels (visually) to Port Clinton, Ohio, home of the Liberty Aviation Museum, repository of the Hogan's Heroes uniforms and props, for a big band version of the "Hogan's Heroes March."

Jodie takes a look back at 2018 at Garroway at Large, along with an update on her Dave Garroway biography. I can't wait to read this; Jodie says she's beginning to understand Garroway, and that should be fascinating.

Martin Grams tells us how we can help save Popeye the Sailor. It has to do with Warners' release of volume four of the Popeye cartoons, which starts in on the 1940s. As seems to be the way of things nowadays, Warners says there will only be additional volumes released if the sales volume demands it. Popeye fans, you know what to do.

Take a listen to the latest edition of TV Confidential; film and television actor Kirk Bovill and television historian Steve Randisi will join Ed Robertson this weekend for a brand new edition , airing January 4-6. Follow the link to find out where and when you can listen.

And by the way, as I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I'm on Twitter now, so be sure to follow me for treats not available on the website. Speaking of which, there'll be another TV Guide on the website tomorrow; come back then. TV

December 14, 2018

Around the dial

It's the last edition of "Around the Dial" before Christmas, so let's see what kind of shiny things might be under our classic TV Christmas tree!

It's Volume 1, Number 11 of The Twilight Zone Magazine on tap this week at Twilight Zone Vortex, and among the features, Gahan Wilson reviews John Waters' Polyester, Tom Seligson interviews Wes Craven, and it's Part Eleven of Marc Scott Zicree's essential TZ episode guide.

In a related development, David has another installment of "The Unshakeables" at Comfort TV: this one is Rod Serling's seminal 1955 teleplay Patterns, as presented on Kraft Television Theatre. So large was the impact of this live broadcast that it was restaged again a month later—remember, this was the era of live TV.

Speaking of sci-fi: proof that truth can be, if not stranger, at least more fantastic than fiction, is shown at The Federalist, where Howard Chang and Jordan Lorence look back at the Christmas Eve, 1968, broadcast of Apollo 8, and how it was a "Christmas miracle for a weary world."

At Television Obscurities, Robert answers a reader's question about the 1973-74 program The Burt Reynolds Late Show, which aired in place of the Saturday Tonight Show reruns in the days before Saturday Night Live took over the timeslot. Talk about obscure; I have no memory of this, although seeing as how this was during my exile in The World's Worst Town™, we would have gotten a local movie in that timeslot instead. But I'm in a good mood now, so don't get me started with those memories!

Finally, a blog note: we're now on Twitter, so be sure and follow us here; as I continue to build up the feed, look for exclusives you won't see here, as well as links to more classic TV goodies. TV

It's Volume 1, Number 11 of The Twilight Zone Magazine on tap this week at Twilight Zone Vortex, and among the features, Gahan Wilson reviews John Waters' Polyester, Tom Seligson interviews Wes Craven, and it's Part Eleven of Marc Scott Zicree's essential TZ episode guide.

In a related development, David has another installment of "The Unshakeables" at Comfort TV: this one is Rod Serling's seminal 1955 teleplay Patterns, as presented on Kraft Television Theatre. So large was the impact of this live broadcast that it was restaged again a month later—remember, this was the era of live TV.

Speaking of sci-fi: proof that truth can be, if not stranger, at least more fantastic than fiction, is shown at The Federalist, where Howard Chang and Jordan Lorence look back at the Christmas Eve, 1968, broadcast of Apollo 8, and how it was a "Christmas miracle for a weary world."

At Bob Crane: Life & Legacy, Carol recalls the wonderfully surrealistic Hollywood Palace Christmas show of 1965 in which the entire cast of Hogan's Heroes, in character, appear as guests with their "boss," host Bing Crosby, whose production company was responsible for Hogan. Yours truly is quoted in a very nice article.

Martin Grams reviews Side by Side: Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis on TV and Radio, a new book by Michael Hayde, that takes a look at a part of the duo's legacy that isn't often discussed: their work on radio. I have Hayde's very good book on Dragnet; this one should be equally interesting.

At Television Obscurities, Robert answers a reader's question about the 1973-74 program The Burt Reynolds Late Show, which aired in place of the Saturday Tonight Show reruns in the days before Saturday Night Live took over the timeslot. Talk about obscure; I have no memory of this, although seeing as how this was during my exile in The World's Worst Town™, we would have gotten a local movie in that timeslot instead. But I'm in a good mood now, so don't get me started with those memories!

Finally, a blog note: we're now on Twitter, so be sure and follow us here; as I continue to build up the feed, look for exclusives you won't see here, as well as links to more classic TV goodies. TV

December 1, 2018

This week in TV Guide: November 27, 1965

There was, once upon a time, an era in which the biggest college football game of the year was played on the last weekend in November. It was the game between Army and Navy, played at Philadelphia Stadium, attracting well over 100,000 people each season. The teams were perennially among the best in the nation; Army won the national championship in 1944 and 1945, while Navy finished the 1963 season ranked #2, and in the twenty years between 1945 and 1965 the two schools combined to produce five Heisman Trophy winners.

There was, once upon a time, an era in which the biggest college football game of the year was played on the last weekend in November. It was the game between Army and Navy, played at Philadelphia Stadium, attracting well over 100,000 people each season. The teams were perennially among the best in the nation; Army won the national championship in 1944 and 1945, while Navy finished the 1963 season ranked #2, and in the twenty years between 1945 and 1965 the two schools combined to produce five Heisman Trophy winners.By 1965, however, things had changed. For one thing the venue in which the game was played, although it was the same stadium, was now called John F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. For another, the two teams had started their long decline into football irrelevance. The symptoms weren't readily apparent; the 1965 teams were said to have had "disappointing" seasons (4-5 for Army; 4-4-1 for Navy, who'd lost Roger Staubach to graduation the previous year), and a crowd of 102,000 was expected, including President Lyndon B. Johnson. The teams played to a 7-7 tie.

It seems as if we're always talking about how dramatically televised sports has changed over the years, and here's another example. Later that Saturday afternoon, CBS's NFL Countdown features live reports on the "NFL college-player draft," being held at the Summit Hotel in New York. You'll note first of all that the draft is being held in November, rather than April of the following year. It's not only before the end of the college season, it's also before the NFL season ends.

Today, of course, the draft is a TV spectacle, with two nights of prime-time coverage on three separate networks (ESPN, NFL Network, and Fox). Draft parties are held in cities throughout the country, and TV draft experts are a cottage industry.

But that's not to say that the pro football draft in the 1960s was without drama.* For one thing, the NFL had competition from the AFL. Each league held their own draft, with the result that most of the top players were drafted by a team from each league. The battle to sign the top draft picks was fierce, and stories abounded of scouts from one league hiding players in hotel rooms under fake names, spiriting them away in the trunks of cars, and doing anything they could to keep them away from their rivals in the other league. Many college players made a ceremony of coming to terms with a professional team, often signing the contract under the goal posts after their final college game. (Some others, of course, signed before their final game, but that's another story for another time). With the increased competition came, naturally, increased salaries, which went through the roof. This ended in 1967, when as a precursor to the NFL-AFL merger the two leagues for the first time held a common draft, in which all teams took part, alternating picks. It was an end to the bidding war between the leagues, although the era of big-money contracts was here to stay.

*Not to be confused with the military draft, drama of a different kind altogether.

📺 📺 📺