I've been doing this gig now for what, 12 years? You'd think I'd know the answer to that, but it's been demonstrated that many of you out there are more familiar with what I've written than I am. Anyway, during all these years, one of my constant themes has been the intimate role that television has played in people's lives. This week's lead story, by Joanmarie Kalter, examines how television "shapes the lives" of people in retirement communities—how, in fact, it is the only link to the outside world for many.

Kalter reports from On Top of the World, a middle-class condo community of about 8,000 in Clearwater, Florida, where the residents aren't afraid to admit that not only do they watch a lot of television, they love doing so. (I wonder if it's too late to get a condo there.) They use it for, among other things, keeping track of the world. "I do like to tune in on Washington Week," says Arley Sica. "And I'll tell you why. Those fellows are specialists. They have contacts in the Pentagon, entree to Congress. They're very important for understanding the news of the week." Among other favorites, they enjoy watching Wall $treet Week, 20/20, Dallas, Cosby, and Dynasty. He'd go into more detail, but he excuses himself, telling Kalter that it's time for the news.

Helen Martin looks at Today hosts Jane Pauly, Briant Gumbel, and Willard Scott almost like friends. Clarence Mahrie enjoys Hawaii Five-O, Police Woman and Barney Miller; he likes these kinds of shows that "solve the problems and it comes to a finish, which you know from the beginning anyway. Sophia Karageorges watches shows like Highway to Heaven "where things come out good in the end, because life isn't like that. So you find it where you can." And when dinner's through, everyone crowds around, talking about their favorites, what they like and what they don't ("We already know what goes on in the bedroom," one says about the sexier shows on the tube. "They don't have to show us."), and they just laugh when Kalter tells them that TV often portrays older men as "bad" and older women as "unsuccessful." Says one woman, "Television is the best thing that was ever invented. That's all I can say." (These people really are kindred souls.")

Although advertisers poo-poo them, senior citizens are among television's most loyal viewers. They're also among the wealthiest; according to business-research group The Conference Board, "poverty rates among the elderly are now lower than for others, while those aged 65 to 75 enjoy more income per person than those under 45; 'The older consumer, so cavalierly ignored by so marketers, is in fact the prime customer in the upscale market.'" And slowly television has started to respond: Murder, She Wrote, The Golden Girls, Joan Collins, Lauren Bacall, and others are showing that "consumers in retirement are not ready to be old; what they seek, instead, is a final chance to be young."

Television does more than just fill time for these people; rather than being turned into couch potatoes, it keeps them involved. They're "far from old friends, from children, from work and the old home town," Kalter points out, and "television bridges the distance; it keeps them involved." They watch the news, they keep track of movies, they look for public television to replace the culture they left behind in big cities. It stimulates the mind, one person says, and adds, "There are some ladies here who just sit and sleep. They don't know nothing from nothing. It's a shame." The rhythm of their day is shaped by what time their favorite shows are on, and, says 84-year-old Miriam Hartline, "I'd be lost, terribly lost without it."

Kalter charmingly describes this generation as one "for whom the wonder of television has never quite worn off." "It's all still new to us," Mary Brown says, and I understand exactly what she means. The residents all recall their very first set (so do I), and whether or not they took out a loan to get it; they remember the small screens and the magnifiers that were used to enlarge the picture, and they remember "how the neighbors would all crowd in to see it." They are fond readers of TV Guide, and they carefully mark the shows they plan to watch. They're purposeful on their viewing, and don't leave the set on as background noise. For them, television is not something to be taken for granted.

A few years ago, a writer in his late-twenties named Rodney Rothman wrote a book called Early Bird, about his experiences living in a Florida retirement community for a few months because he wanted to "practice living old," and it now appears that I’ve spent more or less my entire life doing just that, sitting in front of the television when I could have been out somewhere breaking world records or curing diseases or changing the destinies of various nations. The flip side of that, of course, is that I might not have survived to write about any of this, whereas watching television is a fairly sedentary activity where the risks are limited to things like diabetes and obesity and high cholesterol. But, you see, those people in Florida have that beat, because they’ve already lived through most of life, and if they do come down with any of these diseases, well, it’s probably better to have them at the end of your life instead of when it’s just starting out. That may sound cold, but it’s also probably true. My way, the biggest risks are those that you assume by reading what I write

l l l

I know this might be a bit hard to swallow, but there was a time when Cosmopolitan was a sophisticated magazine, It was famous for publishing novellas and short stories by writers who were or would become famous; H.G. Wells, O. Henry, A. J. Cronin, Sinclair Lewis, George Bernard Shaw, Upton Sinclair, and Jack London were just some of the authors who had their works published in the magazine.

Then, Helen Gurley Brown became the editor, and turned Cosmo into a soft-core porn rag.

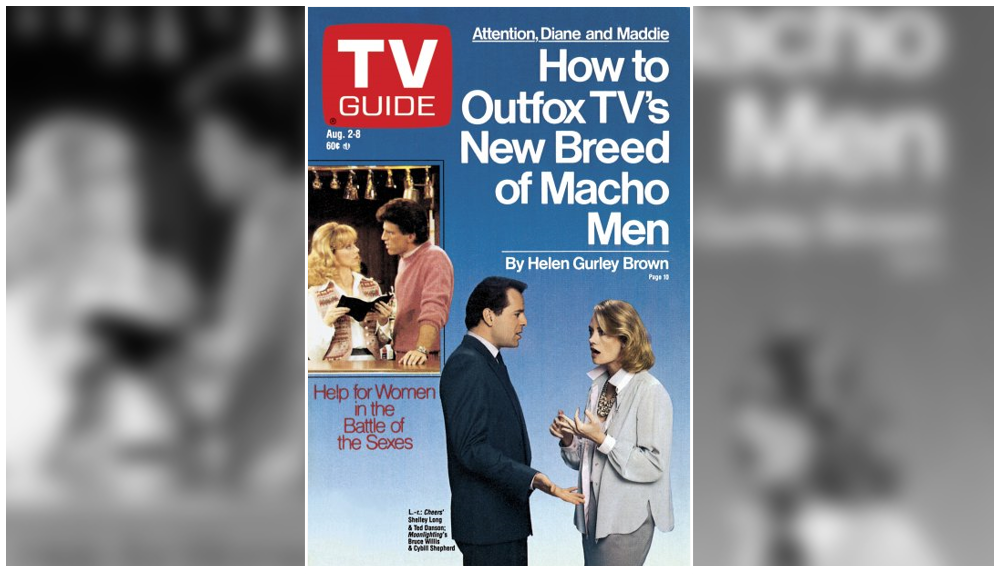

I wonder if Helen Gurley Brown would have been published in the TV Guide of the 1950s or '60s, or even the '70s? We're past that point now, though, and so she features in this week's article, "How to Outfox TV's New Breed of Macho Men." It even reeks of sensationalism, doesn't it? The "macho men" in question—perhaps they'd be called "toxic males" today—are Sam Malone, aka Ted Danson, of Cheers, and David Addison of Moonlighting, also known as Bruce Willis. Now, I'll admit right off the top that I never watched either of these series, nor do I read Cosmopolitan, so I'm basing all my opinions on their respective reputations, as well as my skill at reading about popular culture.

As Brown enters the scene, her question is a simple one: why do these women spoon for men who are "probably the wrong men," men who'll make them losers even if they win? "Smart Women, Foolish Choices!" she says. Take Diane (Shelley Long), for instance—smart, sensitive, attractive; "why is she hiding her brains in Sam's bar, waiting on machos and men who are afraid to go home to their wives?" Even if she does succeed in landing Sam, she'll still be working at the bar, while he's out playing the field. (So much for the redemptive love of a good woman, I guess.) Here's Brown's prescription for Diane: "Let Sam propose to slick councilwoman Janet Eldridge," she says. "That way, Diane can have the more rewarding role of The Other Woman. Sam is bound to cheat on Janet once he has her."

As for Maddie (Cybill Shepherd), she's stuck pining for "a Peter Pan unwilling to grow up." Her suspicion is that Maddie would find David a better lover than husband, so she suggests the writers consider having Maddie give in to him. Or they could "have Maddie make the first official move on David, with him being chased around the desk and told he could either give in our lose his job." Wouldn't that be a switch? After all, she's the boss of the firm, and if things go south, it's always the lesser person

According to Brown, both Diane and Maddie are suffering from "a real-life condition: men who are unwilling to face the responsibility and lack of excitement of a long-term relationship." All Diane gets is "great verbal sparring at which she wins only some of the time." Maddie, meanwhile, is "so involved with David professionally she doesn't get much of a chance at an outside life in which she might meet a prince." Could Diane and Sam, and David and Maddie, live happily ever after? Brown doubts it, and besides, "Their series would be canceled."

The whole article, well-written and witty though it may be, sounds exactly like one would get from a magazine like Cosmopolitan. And while some of her advice is actually insightful—Diane, for example, "may seem a feminist but is actually caught up in the time-honored, one-sided love affair in which a masochist is more in love with a semi-sadist than he is with her."—the whole thing seems, I don't know, so—shallow. There's no depth to these relationships, which always revolve around sex and sexuality, rather than sense and sensibility. And overriding all of this is the idea that for men and women, true equality means letting women benefit from easy sex and shallow connections, just the way men do. I know that there's more to this article than that, but really: isn't the Cosmo lifestyle just the Playboy philosophy for women? I rather think that the answer lies not in bringing women down to the level of men, but raising men to the level of women. But then, I'm old.

l l l

It's what Judith Crist calls a "between-seasons" movie week; that doesn't mean, however, that it lacks for quality. The week's major premiere is that of David Lynch's magnificent The Elephant Man (Monday, 9:00 p.m. PT, NBC), featuring a "remarkable performance" by John Hurt as John Merrick, for which Hurt received a well-earned Best Actor nomination, coupled with Anthony Hopkins' compassionate performance as Frederick Treves, who struggles to help Merrick. The black-and-white cinematography paints a grim picture of Victorian London, and Lynch's direction gives a disorienting aspect to a movie that could easily have drifted into sentimentality in the hands of a lesser director. The result is a movie that makes "a deep mark in our sensibilities."

l l l

It's football season again, at least the practice version, euphemistically referred to as "pre-season" games. On Saturday afternoon (11:30 a.m., ABC), Wide World of Sports presents the NFL Hall of Fame Game from Canton, Ohio, pitting the New England Patriots and St. Louis Cardinals. The Patriots are off of a 46-10 drubbing in the Super Bowl at the hands of the Chicago Bears, but the real attraction of this game is at halftime, with highlights of the Hall of Fame induction ceremonies, with honorees including Paul Hornung, Fran Tarkington, Ken Houston, Willie Lanier, and Doak Walker. What a group.

On Sunday, the league takes its road show overseas, as those very defending champion Bears take on America's team, the Dallas Cowboys, from Wembley Stadium in London, England. (10:00 a.m., NBC) It's the first game of what would come to be known as the "American Bowl" series of pre-season games played outside the United States; while most games in the early years were played in London, the sites expanded to include Japan, Germany, Mexico, Australia, Ireland, Spain and Canada, before being phased out in 2005. Nowadays, the overseas games get played during the regular season.

There's one more Hall of Fame worth celebrating, though; on Sunday, ESPN has coverage of the National Baseball Hall of Fame ceremonies; the great Willie McCovey, who hit 521 home runs during his illustrious career, is the sole inductee from the Baseball Writers Association of America, guardians of the gates of the Hall. Bobby Doerr and Ernie Lombardi were elected by the Veterans Committee.

We all know the start of the NFL season means the practical end of any other sport, but they keep trying; on Thursday and Friday, ESPN presents first- and second-round coverage of the 68th PGA Championship from the Inverness Club in Toledo, Ohio (11:00 a.m.); Bob Tway wins his only major with a two-stroke victory over Greg Norman.

l l l

There are a few other things of note in a month that's usually given over to summer reruns. On Saturday night, we've got a couple of failed pilots, and it doesn't take a genius to figure out why: In The Family Martinez (8:30 p.m., CBS), Robert Beltran plays a young lawyer who, on his first day in court, has to figure out how to sneak his fugitive client back into jail. Maybe not the worst plot in the world, but what do you do for an encore? Later (9:30 p.m., NBC) Sylvan in Paradise stars Jim Nabors as an inept but well-meaning bell captain at a Hawaii hotel, where his disasters have a way of working out for the best. That one's all too predictable, even with Brent Spiner playing a man with the unlikely name of Clinton Waddle. After that, a name like Data seems almost normal.

On Sunday, Motown Returns to the Apollo (8:00 p.m., NBC), a three-hour, star-studded tribute marking the 50th anniversary of the famed Harlem theater, dominates the evening. It's hosted by Bill Cosby, and stars Smokey Robinson, Stevie Wonder, Sarah Vaughan, Diana Ross, Sammy Davis Jr., the Commodores, Lou Rawls, Mary Wells, the Four Tops, Martha Reeves, Luther Vandross—well, just about anyone and everyone you can think of, plus Rod Stewart, Boy George, and Joe Cocker thrown in. Anyone left out is due strictly to tired typing fingers.

Throughout the week, PBS's American Masters has "The Long Night of Lady Day," a 90-minute documentary on the often-sad life and hard times of jazz great Billie Holiday. I'd try catching it on Tuesday, unless you're committed to watching 1986, (10:00 p.m.), which was NBC's 14th failed effort at putting together a weekly newsmagazine. It's hosted by Roger Mudd and Connie Chung, and as I recall, the most notable thing about it was that it used the Rush song "Mystic Rhythms" as the theme. It was probably also the best thing about it.

There are a host of other relics of the '80s, lesser series that failed to reach the heights of, for instance, St. Elsewhere, Hill Street Blues, Magnum P.I. or Cheers but still help to define a decade: Knight Rider, Remington Steele, Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, Silver Spoons, Hunter, Hotel, Perfect Strangers, Webster, and others. It's far from my favorite decade of television, but, as we've seen today, there's still enough to keep viewers occupied.

l l l

The reason I chose this particular issue to look at this week was that I felt in it was a foreshadowing, as it were, a shape of things to come. I spent a lot of time looking at two articles that didn't really have all that much to do with what was on television, but they said a lot about what kind of people we were to become.

I enjoyed the article about the Florida retirement community immensely. It reminds the reader that television is fun, that there's no such thing as hate-watching a program—if you don't like it, you don't watch it. Viewers discuss the shows not over social media, but around the tables after lunch or dinner, and trade stories about their favorites. And yet, you can see a shadow of the future, can't you? Some can't afford any kind of entertainment or exposure to the world other than television. Many of them no longer have family and friends around; they've all moved away or died. There's an isolation to their lives, even if it doesn't weigh them down. But that isolation will only increase over the years, and not just for the elderly, but for everyone. We all live in our own little worlds now, the metaverse, or whatever kind of alternate reality you want to call it, and if that wasn't bad enough, the absurd virus lockdown was about enough to finish us off.

And while Helen Gurley Brown's article had its moments, it points toward the pornographic society we live in today, one where everything goes, and magazines like Cosmopolitan are at the forefront of it. They've succeeded in making women as randy and debauched and depraved as men—that is, if they even recognize such a thing as women, among all the genders, and cis-this and trans-that and how to have sex with anything that moves. I suspect Brown's Cosmo was tame compared to today's, but you still know them by their fruits.

A fascinating issue, and at the end of the day I'm pulled back to the movie about the New York World's Fair on PBS. The World of Tomorrow, that fair was called. Indeed, we now live in the world of tomorrow that this issue of TV Guide might have presaged, and as we look back to 1986, we see our own "lost American yesterday." TV