Someone once asked me how it was that I was able to think up topics to write about every week. This was back in the early days of the blog, when I was, I felt, much younger than I am today. At any rate, my reply was that I didn’t think about it too much—it just seemed as if something always came up at the right time: something I saw or read or thought about, something that provided a spark that, a few hundred or thousand words later, wound up on the website you’re reading at this moment.

That’s still the way it is today, although I have to work a little harder to come up with the ideas, and the words don’t flow perhaps quite as easily or as quickly as they used to. But when it happens, it can be a delight, because I don’t have to email people or watch videos or look things up to get my thoughts down. I just have to type. And that brings us to today.

Actually, I did have to do a little reading on this one, because it has to do with an essay in The Georgia Review called "Policing the Procedural (on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit)", by Sarah Rebecca Kessler. As you might guess, it’s all about the police procedural on television, in particular SVU, and because it’s written within the mythology of George Floyd and discrimination and attacks on minorities and the abolition of prisons and the idea that there’s no such thing as a good cop, it’s full of the kind of liberal claptrap you’d expect. (Sorry if that offends you, but it’s true.) Notwithstanding all that, though, Kessler make some excellent points on SVU in particular, and the procedural genre in general, and that's what I want to concentrate at today.

l l l

There are those who will say that this kind of discussion is incidental to television, that the connection is too tenuous. I disagree. I give television more credit than that for the influence it has over viewers; how many people “swear” that something is true, that it actually happened, when in fact it turns out to have been something they saw on a fictional television show.* Therefore, it’s not at all implausible that people would take as fact something they’d seen on a procedural, and that it could influence law enforcement policy.

*Case in point: Sarah Palin never said she could see Russia from her house; it was Tina Fey.

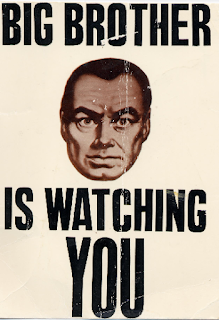

We see them routinely treat suspects with contempt, use surveillance techniques with little regard for civil liberties, and regard the public in general as an inconvenience at best, a constant threat at worst. Not just to the lives*, but to an existential existence, a series of restraints increasingly handed down by a ruling elite dedicated to limiting free expression as much as possible. We’ve seen how the modern police force has evolved into a paramilitary unit, wearing black body armor, enforcing laws that, more and more, come to resemble an ideological tract rather than anything necessary for civil order. They even view video footage taken by eyewitness as somehow a threat to them doing their jobs. They are, of course, “just following orders,” a defense that didn’t work all that well at Nuremberg.

*Kessler describes SVU’s Olivia Benson as “a cop who, as cops do, often uses the phrase ‘good shooting’ to describe the killing of a civilian for the alleged crime of making a cop feel scared.”

Kessler is a fan of SVU (a paradox she freely admits), which gives her a certain credibility when it comes to critiquing the show and what it stands for. I, on the other hand, pretty much hate the program, and I’ve been a harsh critic of it in previous posts here. And, as I mentioned at the outset, Kessler and I come to the discussion from opposite poles: she from the left, me from the right. Still, there are areas where our interests overlap, and we share some of the same concerns about the way in which the police deal with the public and the way they see their jobs.

Kessler wonders, rhetorically, “what it is that makes the cop show, and SVU in particular, so resistant to reproach and immune to reform,” and supplies a ready answer: cop shows tell the story from the cop’s point of view. The Wizard of ID once said that the real Golden Rule was, “whoever has the gold, rules,” and the same goes for the television series: notwithstanding a series featuring antiheroes, for the most part the stars of your show are going to be the good guys, everyone else is the bad guys, and the stories are going to be told from the hero’s vantage point.

Indeed, one of the sure ways to tell whether or not a cop faces a harsh disciplinary action for stepping over the line is whether or not that cop is a regular. Unless the star is involved in some kind of contract dispute with the show, you’re never going to see their character face a lengthy suspension, or even jail time, In fact, featuring the bad cops as guest stars simply serves to reinforce the essential goodness of the system. (Imagine Mariska Hargitay missing for half the season.) Regarding the trial of Derek Chauvin, the officer most publicly held responsible for the death of George Floyd, Kessler asserts that, "It was as if the proceedings had realized SVU’s central fantasy that 'a few bad apples' does not a broken system make."

l l l

In the wake of the Floyd death and Chauvin trial, writes Kessler, what was at issue "was not only the usual positive media coverage of the police, the 'thanks to our brave men in blue' that reliably precedes the names of the victims of a wholly preventable tragedy, but the scores of other televisual fare from reality formats like Cops to scripted dramas like Chicago P.D. that serve as pro–law enforcement propaganda." This is exactly what I've been saying for years, in the form of the argument that these shows wind up desensitizing the viewer to the real threat of authoritarianism, not just from law enforcement in general, but from the government in particular. Or, as Kessler suggests, maybe it's not "desensitizing"—perhaps what it really means is our contentment with the methodology.

How many times have we heard some variant of the line that an innocent person has nothing to fear from the police, that only the guilty insist on their rights, that the most advanced surveillance techniques will only be used against the guilty? This completely overlooks the fact that, 1) it's not the job of the police to determine guilt or innocence, and 2) even if it were, the term "guilt" is likely to be applied retroactively to the suspect at the conclusion of the investigation, given that such techniques were necessary to make such a judgment in the first place.

The police procedural, says Kessler, "normalizes the cop-as-protagonist and the criminal as bit player. There one episode and gone the next, the perpetrator vanishes into incarceration while the victim, the witness, the wrongly accused, the journalist covering the case, and everyone else simply vanishes, leaving the show’s lead cop/s alone to ponder the right, wrong, or, most likely, ambiguity of what has occurred." It's always easy when the perp is painted with a broad brush, practically twirling a Snidley Whiplash handlebar mustache, and it reinforces the viewer's sense that they "had it coming." But if you're looking for a genre to broach the question of actual, real, reform, forget about it: "the police procedural structurally forecloses the question, much less the very real possibility, of abolition, since at the end of the day, the cops cannot be called upon to abolish themselves."

For years I posited the idea that shows like SVU and Chicago P.D. should, as a semi-regular, feature a defense attorney who was tough, competent, and honest—in other words, someone in the mold of Perry Mason or Clinton Judd. (George Grizzard filled the role for awhile, but it was never made a part of the series as it could have been.) There would be no suggestion that the attorney was trying to get his client off on a technicality, or through some other legal subterfuge, only a dedication to the idea that everyone is entitled to a fair trial, and a determination to see to it that justice would be done. In order to maintain the dramatic tension necessary for a television series, the defense attorney would have to lose some of the time, but then there would be times when he won, and then the question would be open and available for everyone to see: What went wrong? Why did we arrest the wrong person?

It would be a breathtaking moment, as far as series television goes, because it would force those characters we've come to know and love to confront the fact that they'd made a mistake, that they'd arrested and tried the wrong person. Since we can't depend on the police to investigate themselves, the defense attorney becomes the medium through which this can be examined. In the serialized environment which television has become, it can’t help but give a series texture when its stars evolve through the course of the series—even grow. Where did we screw up?

l l l

There was a series, once, that tried to bridge the gap, as you probably know. The 1963-64 ABC series Arrest and Trial starred Ben Gazzara as the lead detective, John Larch as the deputy D.A., and Chuck Connors as the defense attorney. It was a unique format, a 90-minute drama divided into two parts: the investigation, resulting in the arrest, and the trial. The crime and the punishment. Said Gazzara of his role, "I'm supposed to be a thinking man's cop. I'm a serious student of human behavior, more concerned with what creates the criminal than how to punish him. In other words, I'm not the kind of cop who asks, 'Where were you the night of April 13th?' It's my job to show that there is room for passion and intellectualism and personal display even within a policeman."

And that's good as far as it goes. Gazzara does, at times, come across as a bleeding heart. But, in my limited viewing of the series, it seems as if the writers try too hard to make sure that both he and Connors are right, that while the defendant might be guilty, there are also extenuating circumstances that mitigate his responsibility for the crime. While [creator] Herb Meadow had suggested that Arrest and Trial would be the 'first series where both protagonists will not always be right each week,' it was a promise that was easier said than done. As Stephen Bowie writes, "The corner into which the writers inevitably found themselves painted was the schism between the motives of the two leads. Arrest and Trial put Anderson [Gazzara] and Egan [Connors] on opposite sides of the judicial process: Anderson’s job was to catch the criminals and Egan’s was to turn them loose. Allowing the principals to be wrong 'occasionally' might have seemed like a good idea on paper, but it meant that every week one of them would have to make a fool of himself — either Anderson arrests the correct perpetrator and Egan loses his case, or Egan sets his client free by proving that Anderson busted the wrong guy." If the show wasn't ready to tackle the Big Questions, nor to give us heroes with feet of clay, then such a format could never work. Law & Order succeeded where Arrest and Trial failed, because they chose to put the emphasis on the “law and order” side of the equation.

A digression, perhaps, but this is, after all, a website dealing with TV history.

l l l

Understand that I don’t intend this as a broadside against all members of the police. Unlike Kessler, I do believe that there are “good cops”; officers and detectives with a desire to protect the public, and dedicated to an even-handed search for truth and justice. (There are also officers, including some of whome I personally know, who are little more than fascist thugs, with an unforgiving view of anyone who opposes him as “the enemy.”)

The indictment I have here is a collective one, of “the police” rather than the policeman, the paramilitary unit instead of the guardians sworn to protect and to serve. Kate Andrews, writing in Britain's The Spectator, describes the result: "We see America’s police officers treat low-level offenders and even innocent citizens with the same force and aggression you would expect to see used against the most violent criminals." Whereas Americans were once governed by consent, Andrews writes, today "America is policed by force." Police procedurals, in the way they dramatize the stories, justify these actions. In a previous essay I wrote on this subject, I quoted at length Gregg Easterbrook, writing about the series Chicago P.D. in a 2014 article at ESPN.com:

But what's disturbing about Chicago P.D. is audiences are manipulated to think torture is a regrettable necessity for protecting the public. Three times in the first season, the antihero tortures suspects—a severe beating and threats to cut off an ear and shove a hand down a running garbage disposal. Each time, torture immediately results in information that saves innocent lives. Each time, viewers know, from prior scenes, the antihero caught the right man. That manipulates the viewer into thinking, "He deserves whatever he gets."In the real world, law enforcement officers rarely are sure whether they caught the right person or what a prisoner might know. Some ethicists say there could be a ticking-bomb exception—if the prisoner could reveal where a ticking bomb is, then torture becomes permissible. But how could a law enforcement officer be sure what a captive knows? And if by this logic torture is permissible, wouldn't that justify torture by, say, the Taliban if they captured a U.S. airman who could know the location of a planned drone strike?NBC executives don't want to live in a country where police have the green light to torture suspects. So why do they extol on primetime the notion that torture by the police saves lives? Don't say to make the show realistic. Nothing about Chicago P.D. is realistic—except the scenery.

Elsewhere in that essay, I added that, with regard to SVU, “viewers are witnesses to an amazing contempt that authority holds for citizens, which extends to every kind of bullying they can think of, including statements that I'd read as being clearly unconstitutional. (My favorite is when they tell a suspect that if they don't talk now, any chance of a deal is gone. Try telling that to some overworked assistant DA who'll cut any kind of a deal to decrease his workload.) These people aren't interested in justice—they just want to win.*” And this doesn’t even begin to touch on the typical trope that an innocent person doesn’t need a lawyer, and that the defendant who wins acquittal does so because of his lawyer’s slick tricks.

*Even in a series like Perry Mason, Mason often argues that once the police find their suspect, they stop searching for the truth.

The point: the justice system, riddled with corruption and ideological agendas from the Department of Justice on down, is its own worst enemy in the best of times; the last thing they need is to have a television show exaggerate the problem.

l l l

“I don’t believe most or any SVU fans, liberal or otherwise, genuinely want the series to “do better”—whatever that even means,” Kessler writes. “As a fan myself, it behooves me to be honest about this fact. I would rather the show (literally) be canceled than ameliorated into something less fun to watch.” Conceding that this might be seen as a “crass” position, she explains, “if the show was just sincerity with no sensationalism, why would I want to watch it? Better a cop show whose absurdity is akin to self-parody than a cop show that’s trying not to be the cop show it most certainly is.”

Well, that depends. It may be true that in the realm of the procedural, Kessler is right when she says that ‘cop shows will always be cop shows,’ whether or not they remain hardline or feebly gesture toward reform.” But are all cop shows procedurals? Again, it depends. Naked City, to my mind one of the finest TV dramas ever, used the framework of the police drama to tell stories of life in the gritty city, often relegating the precinct detectives to the background as the guest stars took center stage. Sometimes an episode would use the flimsiest of pretexts, the slimmest of connections to police work, to tell a story that just as easily could have been told on Route 66. And I cite that story deliberately, as both Naked City and Route 66 were the products of Sterling Silliphant, a writer who could hardly be considered a right-wing law-and-order extremist. Under Silliphant’s guidance, Naked City wasn’t really a police drama; it was a drama about people, some of whom just happened to be policemen.*

*And not just that: I’ll always remember a Naked City episode in which Detective Lieutenant Mike Parker tells an aggrieved New Yorker that, as a citizen, he has every right to bring his problem to the police and expect some kind of resolution. What Parker realized, and today's cops don't, is that the police are the servants of the public, not the other way around.

Kessler doesn’t have any good ideas to offer here, concluding that “instead of disingenuously demanding that SVU and its ilk ‘do better,’ instead of policing the procedural into some illusion of justice, how about demanding an end to policing and to prisons?” This is, of course, a cop-out—no pun intended—because it relinquishes the moral high ground she sought to attain in linking the content of procedurals to the effect they have on their audience. If we’re that concerned about it, then we can’t just shrug and say that, well, that’s television for you, and entertainment is always going to win out over serious content. If you believe that, then why are we even having this discussion?

Perhaps I can speak more freely because I’m not a fan of SVU, Kessler makes a compelling case in linking the content of procedurals, the idea that these shows “desensitize” the viewer to the abuses committed by police. It’s a damning accusation, because it makes us all complicit in the affair, all sharing in the responsibility. To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin, those who would give up their liberty in return for a little temporary entertainment deserve neither. If the analogy of frog and the boiling water holds

Why, then, does she give up so easily? “What might television be in the absence of the promise of punishment on which so many of its genres, programs, and episodes hinge?” Kessler asks. “Can you dream up a cop show without cops?” The answer to that is yes—if you view them not as cops, but as men and women.

Procedurals deserve the criticism they’ve received here, because they reflect a particular philosophy that strikes a sympathetic cord with viewer sentiment. (In other words, they manipulate you.) Kessler and I may not share much when it comes to ideology, but in this limited case we can see eye-to-eye, will say that even if it’s through sidelong glances. The harsh truth, and conservatives are coming to recognize this even as liberals have, is this: When your police force becomes politicized, when it functions not as a law enforcement agency but as an enforcement arm of the ruling class, then the police are not your friends. The sooner you ignore what you see on the tube and believe what you can see with your own eyes, the better for America, and her people. All of them. TV

Much food for thought in this piece. Thanks for writing it.

ReplyDeleteThanks, David. It's probably the kind of topic that merits a much longer reflection, perhaps as a chapter of a book, because I probably overlooked some things that would have made for a stronger argument. I find that as I've grown older, some of my opinions have taken on a remarkable shading, although I still think they're consistent with a holistic philosophy. Thank God I've never stopped finding new things to consider, and different ways to think about things. My younger self, even from 10 years ago, probably would blanche at some of my ideas today.

Delete'me from the far right'. Did you really mean to say that?! Conservative, certainly, but I wouldn't consider you *far* right! You wouldn't have been able to write this blog post if you were. Or read my blog, because you would explode. Lol!

ReplyDeleteThe main omission for police procedurals for me, which you talk about, is if they are actually procedural they never touch on motivation and the inner world of the individual. I think they're better at showing group behaviour and motivation but it really bugs me. It tends to leave the reason people behave the way they do unexplained...

You know, you're probably right. There are those who would describe me that way, and perhaps that's what I was thinking of, along with the rhythmic build of the sentence, but I don't think of myself that way either. (Truth be told, I'm probably a contrarian.) I've fixed that line, for which you have my supreme thanks. And you're also right--I enjoy your blog immensely!

DeleteFrom one contrarian to another, I suspected you would say something like that!

Delete