I know we've been spending quite a bit of time in the 1950s lately, but I'm going to stick with it for one more issue, because I'm a sucker for what the Academy Awards used to be.

The Oscars are yet another topic you've heard me complain about ad infinitum, so if you're sick and tired of it, feel free to skip this portion and go to the next section. The reason I'm even bringing it up now is because the Oscars seem every year to move farther and farther away from what they used to be. I mean, ask yourself—how many of you are planning to watch tomorrow night's show? How many of you have been to more than two of the Best Picture nominees? How many of the acting nominees have you seen in more than one or two movies? How many of you have heard of all three of this year's hosts? How many of you consider the Dolby Theater glamourous?

Now, there are probably a few of you out there, cinephiles perhaps, who can give a positive answer to most of those questions. But here's my next question: how many of the people who watched the 1955 Academy Awards broadcast considered themselves cinephiles, and how many were simply fans of the movies?

Let's look at the list of nominees for Wednesday night's program (9:30 p.m. CT, NBC). First, there's the time itself—7:30 p.m. in Hollywood, which gives the whole thing the air of a movie premiere, with spotlights and screaming crowds flanking the red carpet as the stars stride into the Pantages Theater, one of Hollywood's storied locations. This year's ceremony begins at 5:00 p.m., which means the stars don't come out at night—they appear in the middle of the afternoon. Anyone can tell you that a full moon visible during the day isn't nearly as awe-inspiring as it is in the dark of night.

Then you have the nominees, both the actors and the movies themselves: Humphrey Bogart, Marlon Brando, Bing Crosby, James Mason, Dorothy Dandridge, Judy Garland, Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, Jane Wyman, Eva Marie Saint, Nina Foch, Claire Trevor, Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger. You probably recognize most of these names, if not all of them. Even a lesser-known actor, such as Best Actor nominee Dan O'Herlihy, gains credence by his very inclusion with grand names. (The Oscars were always good at that, and finding those nominees is one way of introducing yourself to very good performances in very good movies.) And the movies themselves: The Caine Mutiny, The Country Girl, On the Waterfront, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, A Star is Born, Three Coins in the Fountain, The High and the Mighty. It's a great night for the movies—and maybe that's another thing: the Academy seems more interested today in films than in movies.

There's only one host in 1955, and there could only be one host: Bob Hope, Who else could it be? And he was charged with keeping the show moving; the listings give the running length at "About 2 hours." (The ad on the left even suggests 90 minutes!) The last time a normal ceremony was held, back in 2020, the running time was three hours and thirty-six minutes; previous ceremonies had been known to eclipse four hours, filled with clips that remind you how much better the movies used to be.

Don't misunderstand me: I love going to the movies, and there are still very good movies being made, movies that feature very good actors. Denzel Washington, for example, is an excellent actor, and I hope he wins tomorrow night. I'll admit that I've not seen a movie starring Nicole Kidman, but the same goes for her. (I read Billy Bathgate though, if that counts for anything.) Some of this year's nominated actors are probably better than some of the actors nominated in 1955. The point is, a great actor isn't necessarily a movie star. Right?

The Academy Awards are all about movies, and they're all about glamour. They're missing too much of the former, and too much of the latter, and that's why I miss what they used to be.

l l l

Oh, one more thing about Wednesday's show—the nominated songs and their singers. Dean Martin sings "Three Coins in the Fountain" from the movie of the same name; Johnny Desmond does "The High and the Mighty" from that movie; Rosemary Clooney performs "The Man Who Got Away" from A Star is Born, Danny Thomas sings "Count Your Blessings" from White Christmas, and Tony Martin does "Hold My Hand" from Susan Slept Here. Not a bad lineup of songs or singers, is it?

l l l

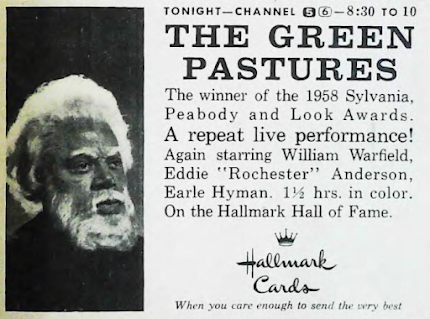

The weekend highlight is the color extravaganza Entertainment 1955 (Sunday, 6:30 p.m., NBC), a 90-minute spectacular to celebrate the dedication of NBC's new Burbank color studios (made so famous in later years by Johnny Carson). It's a showcase of how television can cover "the lively arts," with Helen Hayes presenting the Tony award for Best Play; Dinah Shore in the studio, singing "Whatever Lola Wants"; Leontyne Price recreating her recent NBC Opera Theatre appearance as Tosca; comedy from Buddy Hackett, Pat Carroll, and Tom Holmore; Sue Carson doing a nightclub act, and host Fred Allen performing some of radio's greatest moments. NBC executives Pat Weaver and Robert Sarnoff, make a special appearance.

Sunday's a pretty good night on the tube; on Toast of the Town, Ed Sullivan welcomes Rodgers and Hammerstein as they commemorate the 12th anniversary of their celebrated musical Oklahoma! (7:00 p.m., CBS) That's followed at 8:00 p.m. by General Electric Theater, as host Ronald Reagan introduces Henry Fonda as the young Emmett Kelly in "Clown," based on Kelly's autobiography.

Speaking of the circus, John Daly takes us behind the scenes at Madison Square Garden in New York City as Ringling Bros.—Barnum & Bailey prepares to kick off the 85th edition of "The Greatest Show on Earth." (Tuesday, 7:00 p.m., NBC) About half of the hour-long program focuses on the actual acts, while the other half consists of Daly's co-host, John Ringling North, leading viewers on a tour of what makes the Circus tick. The broadcast, which will utilize 12 live cameras at various points in the Garden, required the approval of Cecil B. DeMille, who, as a result of producing the Oscar-winning movie version

The Greatest Show on Earth, had veto control over any television broadcast of the Circus. This year's broadcast is something of an experiment; if it proves to be an effective commercial for the Circus, the cameras will be back next year.

Next on Tuesday's agenda is March of Medicine (8:30 p.m., NBC), a special that provides us with some historical perspective. Entitled "Ten Years After Hiroshima," it's a report on the effect of atomic radiation on the survivors after "the first atomic weapon ever used in war." There's also a look at the U.S. Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, and the work being done by research labs in Boston and Chicago. To me, at least, this is a show that gives one pause; it's not even ten years since Hiroshima, and this isn't some distant memory—almost everyone reading this issue was alive when the bomb was dropped, and the research is based not on theoretical experiments, but on the actual survivors of the blast.

We'll round off the week with Person to Person (Friday, 9:30 p.m., CBS), and tonight Ed Murrow's lead guest is none other than Marlon Brando, who on Wednesday won Best Actor at the Oscars for his performance in On the Waterfront. Ed didn't know for certain that he'd have an Oscar winner as a guest, obviously, but I think he had a better than 20 percent chance of being right. According to the description, Brando plans to "show off his seashell and book collections and his observatory, from which he can see the Pacific, almost all of Los Angeles and the Sierra Nevadas." I can't remember if this show was live or not; I think not, but in any event I wonder if anything changed based on Brando's win.

l l l

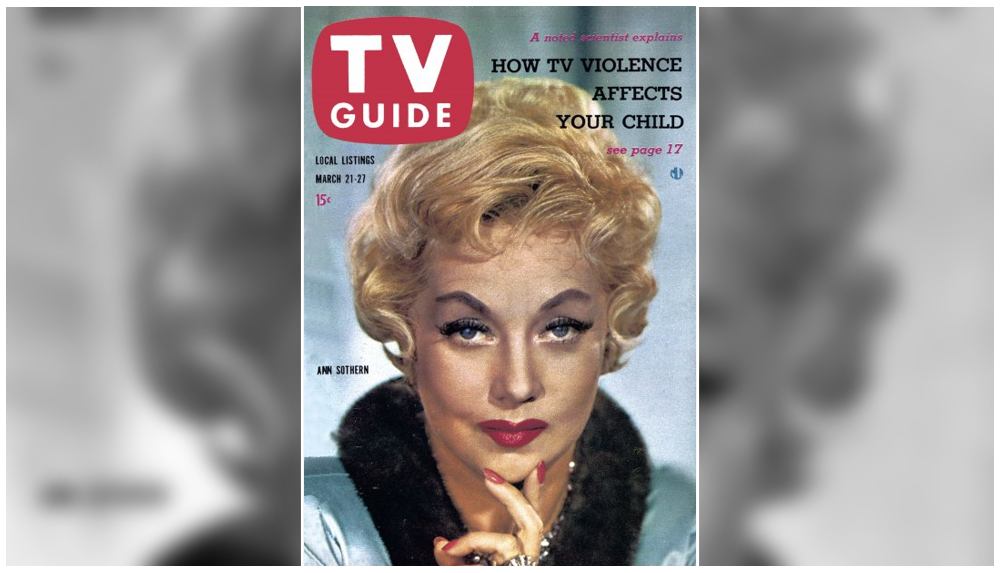

On the cover this week is one of television's favorite second bananas, Gale Gordon. To a later generation, he would be known as the long-suffering Mr. Mooney, one of the many roles he played as the longtime foil of Lucille Ball, but his appearance in this week's issue is as the long-suffering Mr. Conklin, the principal and foil to Eve Arden in both the radio and television versions of

Our Miss Brooks.

In real life, Gordon is anything but the "bellowing" Conklin. He's a pipe-smoker, plumber, carpenter, fruit grower, oil painter, playwright, and gun collector; in addition, he's "one of the few actors in history to appear in a radio dramatic role without saying a word," having played the footsteps of the Unknown Soldier. Somehow, that seems perfect for a man who is about as unassuming as Hollywood stars get.

Gordon seems to have played just about everyone, mostly on radio (including Lucy's boss on My Favorite Husband), and has worked with just about everyone (including Mary Pickford and John Barrymore, who said he had the best diction of anyone "on the stage, radio or screen." He's played Mayor LaTrivia on Fibber McGee and Molly, Inspector Lestrade on Sherlock Holmes (with Basil Rathbone), and in a radio episode of Gangbusters, he played not only the killer, but the cop who arrested him, and the siren that belonged to the cop's car.

Gordon has a rich career, even appearing in Lucy's final TV series, Life With Lucy. You might even say that it was a career to shout about.

l l l

Perhaps the most famous Miss America in history, Bess Myerson has parlayed her crown into regular appearances on television, and it's no wonder. A striking 5-foot-10 in her stocking feet*, Bess has "moved from bathing suits to mink," and it seems that she's thoroughly enjoying it. Last year, she pulled in $125,000 as "The Lady in Mink" on the giveaway show

The Big Payoff, while also pitching products on three major networks, and finding a regular place on various panel shows (she would be a regular on

I've Got a Secret from 1958 to 1967).

*And, the article is quick to mention in the way of the times, her "classical dimensions" of 36-26-36.

It's a very interesting article, as much for what it doesn't say as for what it does. It's been ten years since she became the first (and, to date, only) Jewish Miss America, and while the article makes note on her musical performance at the pageant (an accomplished musician, she wowed the judges with excerpts from Grieg's Piano Concerto), there's no mention of how three of the pageant's five sponsors refused to have her represent their companies as Miss America. (Obviously, television sponsors were far less concerned about her religion.) Much is made of her marriage to Allan Wayne, which produced Barra; there's no indication of the domestic violence that would result in divorce in 1957.

And, of course, still ahead lies her time as head of New York City's Department of Consumer Affairs in 1969; her involvement in big-time Democratic politics, including Ed Koch's successful campaign for mayor, and her own unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate in 1980; and her involvement in a scandal involving her relationship with a married man, her friendship with the judge hearing her paramour's divorce case (and employment of the judge's daughter), and subsequent trial for conspiracy, mail fraud, obstruction of justice, and using interstate facilities to violate state bribery laws (she was eventually acquitted). Ah well, he that is without sin. . .

As starlets go, Bess Myerson is already more successful than most—really, she's already a star—and anyone who's watched her in the old kinescopes of I've Got a Secret that used to run on GSN will remember her as charming, witty, urbane, and still beautiful. Whenever I see her in one of those old reruns, I still prefer to remember that, and ignore the messy stuff. I think she's entitled to that, don't you?

l l l

And just a reminder that if you like what you've seen, there's plenty more where that came from.