July 31, 2023

What's on TV? Sunday, July 30, 1967

Soccer on television has come a long way from the match between Atlanta and Philadelphia on CBS today. Back then, U.S. networks routinely took commercial breaks during play, risking the chance they might miss something important. One way to ensure this didn't happen was to have players fake injuries or referees call "phantom" fouls, causing a stoppage in play that would allow a commercial to be slipped in without missing anything. It's nice to see the spirit of the Quiz Show Scandals hadn't completely gone from television by then. On of today's prestige movies is KTVU's The Naked and the Dead, an adaptation of Norman Mailer's epic war novel, and the source of one of my favorite stories, which I doubt showed up in the movie version. The listings are from the Northern California edition.

July 29, 2023

This week in TV Guide: July 29, 1967

This week we've got yet another article telling us how cable television is going to change the industry forever, and we'll get to that in a bit, but this must be the umpteenth time TV Guide has featured one of these stories, and to tell you the truth, there are only so many ways one can go through them and say, yes, this one came true, and no, this one didn't, and this one did but on your phone instead of your TV. And, seeing how I just read something about how more Americans now get their programs from streaming services than cable, it seems as if we're talking more about what was and what will never be.

So instead we're starting off with a look at a man who's always interesting, Steve Allen.

While The Hollywood Palace is on summer break, ABC fills the Saturday night time slot with Piccadilly Palace, a London-based variety show starring the iconic British comedy duo of Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise. We'll stop in from time to time during the summer months to see who has the best lineup..

Sullivan: In this rerun from Expo 67, Ed welcomes operatic soprano Birgit Nilsson; comic Alan King; singer Petula Clark; the Seekers, vocal group; and choreographer Peter Gennaro, who leads a dance-tour of the fair. Canadian artists: pianist Ronald Turini; singer Claude Leveillee; Les Feux Follets, dance group; and the Montreal Symphony.

I'm not sure we've ever had a Eugene Burdick week here at the blog, but it just goes to show you there's a first time for everything. And before the puzzled expressions you usually have when reading the material here become permanently frozen like some character on The Twilight Zone, I'll explain it all to you.

MST3K alert: Night of the Blood Beast (1958) An alien entity takes control of an astronaut’s body. Is he friend or foe? Michael Emmet, Angela Greene, Ed Nelson, Tyler McVey, Ross Sturlin. (Saturday, 2:00 p.m., KGO in San Francisco) Yet another science fiction movie involving aliens and self-sacrifice, but not quite as good as "A Feasibility Study." In other words, the kind of movie Ed Nelson did before he wound up on Peyton Place. The MST3K version is combined with a really bad short, "Once Upon a Honeymoon," which features Virginia Gibson before she wound up on ABC's Discovery. Well, I guess everybody has to start somewhere. TV

Allen, "the well-known producer, director, actor, comedian, musician, songwriter, sculptor, poet, political theorist, lecturer, biographer and novelist" (in Dick Hobson's words), is being wooed (along with Jackie Gleason and Jack Paar) to return to the late-night wars as host of a new CBS show. He's not enthusiastic about the idea, though, telling Hobson that "(1) I can make a lot more money doing an early-evening show, and (2) it would take too much of my time." Instead, he's content to host the summer replacement Steve Allen Comedy Hour, which gives him the chance to "do satire and social commentary on current events."

In fact, Allen's focus now is on the bigger picture. Asked if he worries about his show's rating, he replies, "I am worried about mankind's rating." He likes the format of his show because it gives him the chance to touch on those issues; "My sketches almost always have a point of view; they're not just silly jokes. We've taken on political extremism, for example, and air and water pollution." He still remembers with distain the time back in 1960, when NBC's Broadcast Standards department "axed as 'too controversial' a serious roundtable discussion of crime and punishment with actors portraying St. Thomas Aquinas, Aristotle, Darrow, Dostoyevsky, Freud, Hegel, Montaigne and Socrates. 'NBC would have preferred that I function in an intellectual vacuum, restricting myself to making audiences laugh rather than think.'" Allen does eventually find someone to take on that idea, though; he's describing Meeting of Minds, which aired on PBS from 1977 to 1981 and rarely failed to fascinate.

Despite his unwillingness to go back to late-night, he does offer a few ideas on what makes a good host. "There may be only four or five guys in the world who can do it," he says (apparently in contrast to the current television fad of thinking that anyone can host a late-night show, and then going on to prove that Allen was right all along). He says there are five keys to success: first, the host has to appear as if he's a non-show-biz type. "The viewer thinks we're just plain folks, just like himself." Second, the audience needs to see you as a good guy. "They should feel toward you as toward a friend. Fast wit and repartee is less important than being likable." Third, "You have to be good at interviewing others and develop the ability to be interested in the person interviewed." Fourth, the host should "be at ease." Bishop, he thinks, isn't there yet. Paar never was, but he was never boring; "his keyed-up-emotionalism made him interesting." Finally (the lesson today's hosts seem to have the most trouble learning), "We shouldn't compete with our guests. I never try to top anybody, especially another comedian."

In the end, Allen successfully wards off CBS's interest in him as a late-night host; they wind up going with Merv Griffin. He does return to the talk wars with a syndicated series in 1968, which ran for three years and was shown at various times of the day in different markets. He writes a successful series of mystery novels in which he and wife Jayne star as fictional versions of themselves, and becomes a vocal opponent of obscenity on television. As I say, always interesting.

l l l

Sullivan: In this rerun from Expo 67, Ed welcomes operatic soprano Birgit Nilsson; comic Alan King; singer Petula Clark; the Seekers, vocal group; and choreographer Peter Gennaro, who leads a dance-tour of the fair. Canadian artists: pianist Ronald Turini; singer Claude Leveillee; Les Feux Follets, dance group; and the Montreal Symphony.

Piccadilly: The rockin’ Kinks and singer Engelbert Humperdinck storm the Palace tonight. Hosts Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise take to the air in scale model planes, and perform a slapstick ventriloquist act. Millicent Martin, Michael Sammes singers.

To be honest, I was seriously considering dropping the Sullivan/Piccadilly segment, or at least putting it on pause. Piccadilly Palace is much more like, say, The Dean Martin Show than it is The Hollywood Palace, which makes it difficult to get a true matchup with Sullivan. And then I looked at this week's lineup, and decided I owed it to everyone to include a show that has the unlikely combination of Engelbert Humperdinck and Ray Davies and the Kinks! For that reason alone, even though Ed has some big name talent, I'm calling the week a Push.

l l l

I'm not sure we've ever had a Eugene Burdick week here at the blog, but it just goes to show you there's a first time for everything. And before the puzzled expressions you usually have when reading the material here become permanently frozen like some character on The Twilight Zone, I'll explain it all to you.

The feature on Saturday Night at the Movies (9:00 p.m., NBC) is The Ugly American, an adaptation of the novel by Eugene Burdick and William Lederer outlining what they saw as failed U.S. policy in Southeast Asia (remember, this was written in 1958); the movie stars Marlon Brando as an American ambassador who fails to understand the complexity of the situation in the region until it's too late.

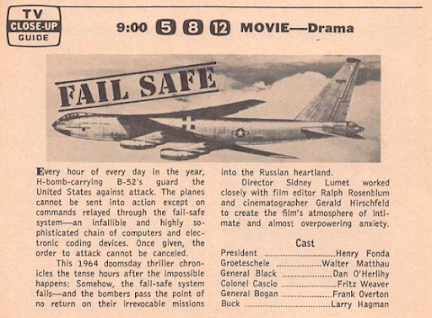

Skip ahead to the end of the week, and the CBS Friday Night Movie (9:00 p.m.) is based on yet another Eugene Burdick novel, Fail-Safe, this one written with Harvey Wheeler. The story of an accidental nuclear war stars Henry Fonda as the president, Walter Matthau (in a very nasty performmance) as a neocon political scientists, and Dan O'Herlihy (in a very sensitive performance) as the Air Force Chief of Staff.

Judith Crist calls the pairing "serious melodramas, topical in theme and honorable in intent," but adds that they "give unconventional themes purely conventional treatment." Despite that (and I haven't seen The Ugly American, but I think Fail-Safe is very good), what I wouldn't give to have more theatrical films of a serious bent like these, rather than a steady diet of action adventure and superhero movies.

l l l

Since we've gotten a head start on the week's activities, let's just keep on going.

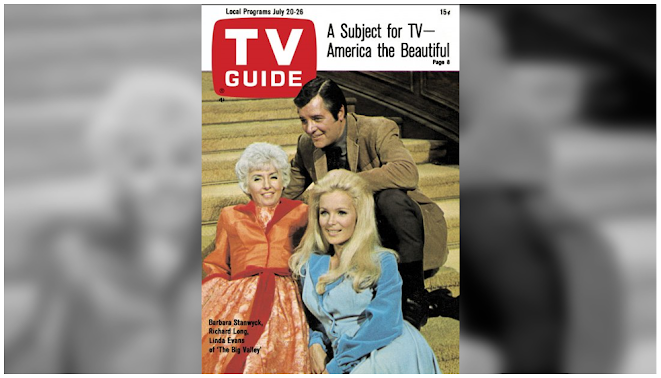

Remember a couple of weeks ago TV Guide featured the cast of the ABC series The Big Valley on the cover? Well, on Saturday, the seventh annual Captain Weber Days Parade (held in honor of Captain Charles Maria Weber, the founder of Stockton, California) has a trio of stars from the show serving as grand marshals: Lee Majors, Richard Long, and Peter Breck. (6:30 p.m. PT, KOVR in Sacramento) KOVR, by the way, happens to be an ABC affiliate. Coincidence?

And speaking of coincidence, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (Sunday, 7:00 p.m., ABC) has a plot that sounds familiar, at least if you read my recent piece on The Outer Limits episode "A Feasibility Study": "An army of rock men attacks the Seaview. The lumbering creatures are commanded by a half-human, half-fossilized madman bent on conquering the world." Frankly, had I seen this earlier, it might have changed my entire understanding of "Feasibility Study." Hmm. . .

On Monday, we have a most interesting cast of guests this week on The Match Game (2:30 p.m., NBC): sportscasters Sandy Koufax, Mel Allen, Curt Gowdy, Kyle Rote and Paul Christman; and former football great Y. A. Tittle. Recognize all of them, and I enjoyed listening to them all. Later in the evening, the same network presents an encore showing of the NBC News Special "Khrushchev in Exile—His Opinions and Revelations" (8:00 p.m.), as host Edwin Newman talks with the former Soviet premier about world events during his time as leader, and the "loneliness and boredom of being banished to oblivion." The documentary was originally shown on July 11, but was pushed out of prime time due to the length of the baseball All-Star Game, a 15-inning affair that ran for more than three-and-a-half hours. By the way, two of the announcers on that game were Curt Gowdy and Sandy Koufax.

Also on Monday, Coronet Blue continues on CBS (10:00 p.m.), which reminds me of a Letter to the Editor this week from Eileen S. Macdonald of New York City, who complains about the network's cancellation of the show without a concluding episode. Her letter, which begins, "I'm so annoyed I can hardly type this letter fast enough," says, in part, "All I can say is that I think it’s a good show, and so does my teen-age son. In fact, we seldom agree on programs and I consider that most of what he watches is junk—that’s why we're a two-set family. Isn’t it time that advertisers woke up and stopped letting the networks push the audiences around?" To that I would say two things: 1) I agree; and 2) Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny aren't real, either. Of course, the story is more complicated than what Ms. Macdonald suggests, but it's certainly unfortunate all-around.

Peter Graves did a lot of B-movie sci-fi before Fury, Court-Martial, and Mission: Impossible, and Tuesday's episode of The Invaders (8:30 p.m., ABC) sounds like it could have been right out of one of them: "The murder of two astronauts prompts David and an Air Force security officer (Graves) to investigate the invaders' interest in the manned lunar program." Joanne Linville and Anthony Eisley guest-star; I'm just sorry we don't get a chance to see Graves's character, wild-eyed, shouting, "You've got to believe me!"

Hands-down, Wednesday's highlight is the KOVR 9:00 p.m. movie, The Third Man, starring Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, Ailda Valli, Trevor Howard, and Bernard Lee. It's a terrific movie, which spawned both a radio series, also starring Welles, and a television series, with Michael Rennie playing as a reformed Harry Lime after the war. This means that Lime survived that shootout in the sewer at the end of the movie, which might be a stretch, but on the other hand, we never did see Lime actually get shot, did we? And as Welles himself once said, "If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story."

Continuing on to Thursday, it's a good night for comedy. At 7:30 p.m., the only regularly-scheduled black-and-white program left on television, The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour (repeats of the 1957-58 series of specials) airs an episode featuring Lucy's new neighbors, Ernie Kovacs and Edie Adams, and immediately starts wooing Edie to get a spot for Dezi on Ernie's TV show. If you're not a fan of Lucy, then I'd recommend an F Troop repeat (8:00 p.m., ABC) in which Larry Storch plays a dual role: Corporal Agarn and his visiting Russing cousin Demtri Agarnoff. I can imagine just how over-the-top Storch was in this episode, which is why I think it's worth watching. I wonder what Hal Horn thinks of this one?

One of the things I really miss from my youthful sports fandom is the College All-Star Game, the football game that matched the defending NFL champions against a group of college all-stars, played at Soldier Field in Chicago. (Friday, 6:30 p.m., ABC) This game, along with the Coaches All-America all-star game earlier in the month, signaled the unofficial start of the football season. I've written about it before so I won't bore you with the details, but as the Green Bay Packers were my team, you know I was rooting for them here. They'd beaten the Stars 38-0 the year before, and even though this year's All-Star team features Steve Spurrier, Bob Griese, Floyd Little, Bubba Smith, Alan Page, and others, the Packers crush them again, this time 27-0.

l l l

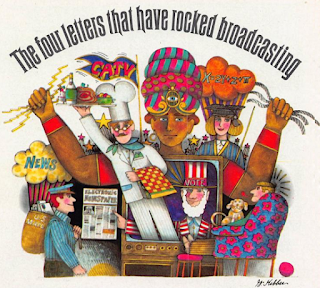

And now that story about cable TV.

CATV, according to Albert Warren, represents "the four letters that have rocked broadcasting." Until recently, cable has mainly brought TV to rural and isolated areas not able to otherwise get a decent signal. (Average cable bill: $5 per month.) But now, it's being rolled out in more metropolitan areas as a kind of test—New York City, for example—where skyscrapers can interfere with clear signals. "The facts are that scarcely anyone in New York can get all nine with the consistently high technical quality CATV [especially color broadcasts] would provide."

One of the beauties of CATV is that there's no technical limit to the number of channels you can transmit through the cable. Most have space currently for 12, but "engineers are working on systems providing 20, 30 or more." The growth of cable is limited for now by the FCC, which narrowly voted to maintain severe restrictions, such as not bringing in stations from distant cities, and not originating its own programming. The rationale is that since local stations require both large viewing audiences and sponsor advertising in order to maintain free program, it would be unfair for them to have to compete with cable. There are also questions about copyrighted material, for which CATV operators say they're willing to pay a "fair rate," but a couple of recent conflicting court cases have suggested Congress will probably have to get involved eventually.

There's plenty of speculation as to what the CATV system of the future will look like: "electronic newspapers, shopping, teaching, voting, surveying, gas and electric meter reading, library research, mail delivery, emergency warnings—you name it. Even now, CATV provides news, weather services and even stock quotations on channels not occupied by local TV stations." (I noticed there was nothing about 24-hour sports networks, but then who could possibly be interested in that?)

There's more, but I think you get the gist of it. One of the intriguing footnotes is that all three broadcast networks have "dipped their toes" in the cable pool; "ABC was hot about CATV for a while, but it marked time while the FCC considered its merger with ITT. CBS has been quietly buying systems—but all in Canada, to gain operating experience while avoiding the complications of U.S. ownership. NBC has bought a couple of small systems, also for toe-dipping purposes." Today, of course, NBC is owned by a cable system, Comcast, and each network is involved, in one way or another, with streaming services. We've already passed throught the expansion of cable and now we're seeing its contraction. As for what comes next, I think one would be a fool to even try and predict what even the next few months have in store. But it's safe to say that those four letters rocking broadcasting have been replaced with three words: Cut the Cord.

l l l

Some assorted notes to round out the week: this week's "As We See It" concerns CBS's recent inquiry into the Warren Report on the assassination of President Kennedy. Running for an hour each night for four consecutive nights, June 25 through June 28, the editors call it "a major journalistic achievement," revolutionizing the way such information is presented by spreading it out over multiple evenings rather than telling it all in a three- or four-hour documentary. The content was "supurb" as well, "a masterful compilation of facts, interviews, experiments and opinions—a job of journalism that will be difficult to surpass." Most important, the shows were a ratings hit, beating almost every show that was scheduled opposite it, and proving that "[w]hen serious programs that interest them are scheduled during prime time, viewers will tune in." Would they do so today? Well, it depends on whether or not you think we're still a serious people. I remember my seven-year-old self being fascinated by this, but then I always was precocious.

A sign that cooler heads have prevailed is evident in the Hollywood Teletype, which reports that "the idea of having a girl for Leonard Nimoy in Star Trek has been abandoned." It's also a sign that there was some level of insanity in the NBC executive offices to even consider such a thing. I guess not everyone back then was "serious."

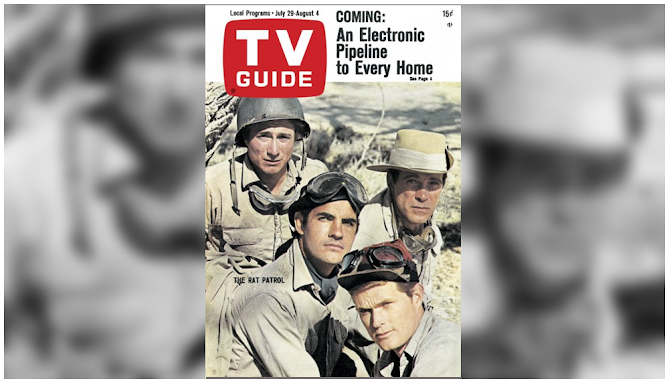

Finally, there's that cover picture on the stars of The Rat Patrol. As you may recall, that show was a favorite of mine when I was growing up, but took a severe dive upon rewatching last year, enough so that it's now on the resell pile. But it's worth a mention that the feature is a profile of Gary Raymond, the English actor who plays Sergeant Moffitt, the most likeable of the four members of the team. And, according to Leslie Raddatz's story, he seems like a pretty good guy. Glad to hear it!

l l l

July 28, 2023

Around the dial

We'll start the week, as we often do, at bare•bones e-zone, where Jack's Hitchcock Project has moved on to the teleplays of Frank Gabrielson, starting with the third-season episode "Reward to Finder," a terrific story starring Oscar Homola and Jo Van Fleet. It's another example of the importance of the writer—in this case, Gabrielson turns a good short story into an exceptional half-hour program.

I hope you've been reading John's series on The X-Files and the American Dream over at Cult TV Blog. I probably say that, or some variation of it, every week, but this is the kind of thoughtful analysis of a program's content that I really appreciate. This week it's a look at episodes that deal with PTSD, government actions that belie what America is supposed to stand for, and more. Whether you agree with it or not, it's great stuff.

We're almost to the end of July (can you believe it? With the heat we've been getting here in Indiana, I certainly can), and that means Joanna is winding down to the end of "Christmas in July." There are several stories to choose from, as this is a daily feature throughout the month, but I'm going to single out a personal favorite, "Blackadder's Christmas Carol," which is a useful, cynical antidote to the sometimes syrupy Yuletide stories we can get.

At The Last Drive In, it's part three of Science Fiction Cinema of the 1950s, and the classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Now, I know this isn't a television post per se, but I think we can all agree that many of these movies became classics through late-night TV viewing. And, for those that aren't true artistic classics, we can thank them for becoming riffing fodder on MST3K!

At Garroway at Large, Jodie talks about the added benefits that came from writing her biography of Dave Garroway, including the people you meet and the friends you make. She mentions your humble scribe and my wife (the feeling goes double from us!), and focuses on her recent time together with Dave's daughter Paris, who sounds like a wonderful person. I'll second what she says; it's easy to say this because I won't be winning awards, but I wouldn't trade a fistful of them for all the friends I've made along the "It's About TV" way.

David's latest at Comfort TV is on how you can't lose em all, or how some of our favorite episodes come from times when the perennial loser finally wins one. This week's example comes from the "Farmer Ted and the News" episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, in which our erstwhile newscaster Ted Baxter (and who'd have thought we'd have more confidence in him than in the news readers we have today) pulls one over on Lou Grant. (And I would have enjoyed Dick Dasterdly winning once, too!)

Speaking of movies, at Classic Film & TV Cafe, Rick looks at Strange Confession, one of the six "Inner Sanctum" movies starring Lon Chaney Jr. You OTR buffs will remember Inner Sanctum from the radio, where it ran from 1941 to 1952; it also was a syndicated television series in 1954. Besides Chaney, Strange Confession stars Brenda Joyce and J. Carrol Naish, and in supporting roles, future stars Lloyd Bridges and Milburn Stone.

At A Shroud of Thoughts, Terence has a fun feature on DC comic books based on TV sitcoms. In addition to such well-known series as The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, The Honeymooners, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, and Sgt. Bilko, the list also includes the radio series A Date with Judy. Read about these and more shows that made it on the comic pages.

The latest Avengers episode at The View from the Junkyard is also one of its most popular (and controversial): "A Touch of Brimstone," which features everything from Satanism to whips and bondage, and wasn't even shown in the United States in first-run. Roger and Mike are split in their opinions on this episode; what do you think? TV

July 26, 2023

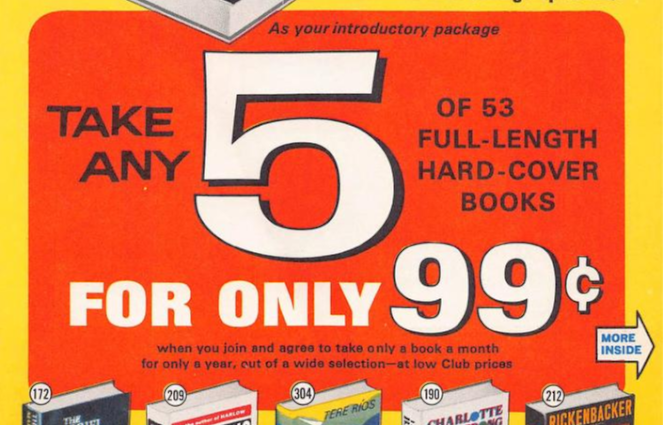

Read anything interesting lately?

Remember those ads in the middle of TV Guide where the issue was stapled together, ads for the book of the month club or the record of the month club or a plastic model of the Apollo spacecraft, printed in color on heavier stock with a perforated reply card? Sure, we all do! If you're like me (and, once again, I hope you aren't), you probably found it hard to resist tearing out the card, folding it back and forth along the perforation until it came off without tearing the rest of the ad, even if you didn't have any intention of sending it in. (I used to use them as bookmarks.)

It's always fun to find one of these intact and unmarked in an old issue. It's another of those time capsule deals; it's fascinating to look at an ad for a book club and see what kind of books people read: how novels weren't all action or adventure or romance but actually dealt with ideas; and how nonfiction books were about history or biography or the works of Shakespeare. And people actually read them! (Or at least impressed their friends, who would think they had read them, which is interesting in and of itself.)

The issue of July 20, 1968, which we looked at last Saturday, has one such ad, and I thought it would be interesting to take a look at it. How many of these books do you remember?

Jacqueline Susann's Valley of the Dolls was a big best-seller back then; there was something scandalous and forbidden about it, even though Truman Capote supposedly called it "typing, not writing." E.M. Nathanson's The Dirty Dozen had just been turned into a movie the month before, so a lot of people would be interested in the book. There are classics like Gone With the Wind and Of Human Bondage, authors like John O'Hara, Catherine Marshall, Chaim Potok, and James Jones; favorites from TV like Art Linkletter and Alfred Hitchcock, and Bruce Catton's Civil War trilogy. There's true crime: books about high-profile accused murderers like Carl Coppolino and the Boston Strangler. And you can't beat five for 99 cents!

My mother belonged to a book club, so I recognize many of these books. Back then I read everything I could find about World War I flying aces, and Eddie Rickenbacker was an early hero of mine, so she got the Rickenbacker autobiography you see on page one. (I still have it, too; it's a fascinating book.) She also had Michel, Michel; I never read that, but it's the kind of story you don't see much in novels today, about a Jewish boy raised as a Catholic in World War II, who now has to decide which faith he will follow. I don't recognize any others, but I know we had many; several of the JFK biographies that were written in the aftermath of his death (my mother knew I'd be interested in them someday), and novels like Paradise Falls and Five Smooth Stones. I don't know what they were about, but I remember the spines. Again, a look at a time long past.

So what about you? Did your family belong to a book club? Did you read any of these? TV

July 24, 2023

What's on TV? Monday, July 22, 1968

The 6:00 p.m. movie on KOVR, Cell 2455, Death Row, is an adaptation of the 1954 book by Caryl Chessman, who at the time was on death row in California for kidnapping and raping two women in separate incidents. No murder was involved, but the law provided for death if the accused was guilty of forcible abduction, and since Chessman dragged both of his rape victims from their cars, he was sentenced to death in 1948. Chessman became a jailhouse lawyer, filing countless appeals, writing four books protesting his innocence while on death row, and getting eight stays of execution, before finally dying in the gas chamber in 1960. He was still alive at the time of this movie, which featured William Campbell as Chessman; he became a cause celebe during the course of his 12 years on death row. A later TV-movie, which is how I learned about Chessman, starred Alan Alda, and that was probably good casting; if your goal is for the audience to sympathize with Chessman, William Campbell is not the actor you want. This week's listings are from the Northern California edition.

July 22, 2023

This week in TV Guide: July 20, 1968

You've probably seen the famous New Yorker illustration "View of the World from 9th Avenue," which depicts pretty much everything other than New York as a vast wasteland. Well, as Edith Efron points out, that's how network news tends to look at this country as well. And NBC's Bob Rogers wanted to correct that, so he conceived, produced, and wrote a documentary called "American Profile: Home Country USA," which presented a very different image of America than the one most people had been seeing. Aired on April 5, the day after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and just weeks before the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, the purpose of the program was to affirm that there was sanity in the midst of the insanity. "For the space of this program, let’s declare a cease-fire in the painful but necessary process of searching, scolding and scaring ourselves," began Chet Huntley's narration. "For a change, we will consider some of our virtues, instead of our faults."

The documentary took viewers on a tour of America, "from a ship-building seaport in Maine, to a Kansas dairy farm, to the tobacco country of south Virginia, to a South Carolina steel plant, to a Texas ranch, to the game-filled Montana mountains, to a Mexican-American town in Southern California." The stars were "the black and white citizens who inhabit the vast geographical expanse of this Nation—those we call the 'grass-roots' Americans." And the result was a program that reminded Americans that this is a big country with a lot that's good about it, a portrayal of "what is enduringly beautiful about the American character."

"The outstanding thing that unites them all is self-reliance," says Rogers. "Each is his own man. They all have strong convictions about what they want, and a willingness to do a fantastic amount of work to enable them to have the career they want and to live the way they want to live. They all have guts." Rogers calls them "The Forgotten Americans."

Why aren't these Forgotten Americans seen on TV? For too long, Efron feels, there's been a perception that "the self-reliant, productive American is 'extinct'—that this country is peopled largely by the dependent, the helpless, the hostile and the violent." TV has played its role in this perception. Rogers acidly notes that it's "Because everybody's covering urban problems," to which Huntly adds his agreement. "It’s true. Our attention has certainly been turned to the cities. That’s where the problems are." He adds, however, "But it is distorted. It doesn’t reflect the total country. We’re ignoring the rest of America."

The degree to which America is being ignored, Efron says, is "enormous." There are more than 200 million people in this country, but "With network news cameras focused on localized, if explosive, urban problems, often photographed in New York City, the mass of this Nation is invisible. TV’s domestic 'window on reality' is mainly showing us social 'evils.'""TV news isn't telling people the way life is," ABCs Howard K. Smith said recently. "Were giving the public a wholly negative picture on a medium so vivid that it damages morale with a bombardment of despair."

It also creates dissention, Efron finds, a view that America is "evil." Rogers says that "The imbalance in coverage is causing Americans to mistrust each other." President Johnson accused the news media of "bad-mouthing this country all day long," and said they have "a vested interest in catastrophe."

|

| Rogers and cameramen Ken Resnick and Richard Norling film cattle in the Big Bend Country |

"Home Country USA" was a needed antidote, a reminder that while America does have real problems, it is also a good country. "It was like soothing balm," in the words of AP reporter Cynthia Lowry, while critic Percy Shain found it a reminder that "There's still a strong backbone running down our Nation's anatomy." People at NBC were moved as well; documentarian Lou Hazam said "It was so thrilling to see these people. They were so real. This show gave us the essence of the American character. The terrific integrity and self-reliance! I can’t tell you what it meant to me." And a viewer from Memphis, where King had been assassinated the day before, wrote to NBC that "With this sorrowful event in our city, most of us became depressed and almost defeated over today’s problems. Your program helped me to remember the rest of America."

Does this America, the real America, still exist? We could use our own "Home Country USA" today, to remind us that there is still goodness and decency in America. We need that reminder that what we see on television and what we read on social media is not the real world. There have been indications that the issues social media emphasizes, the conflicts that it inflames, are not those that consume the majority of Americans, that neither the far-left nor the far-right interest them that much. Now, it's true that this could be whistling in the dark, burying one's head in the sand, and that this equanimity simply allows evil to thrive and accelerates the disintegration of America and the world. When it comes to the future of this country, I'm among the most pessimistic.

But there's no doubt that this real America still exists as a home for most people, and we need to be reminded of that. As Efron says in conclusion, "The soothing 'balm' was the sight of American goodness. It is a vital necessity, in this troubled period of our history, to show it on the screen." It may be heartbreaking, but it may also be inspiring. It may suggest that it's not too late yet.

l l l

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup.

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup.Sullivan: Ed’s guests are singers Eddie Fisher, the McGuire Sisters, and Lulu; comedians Jackie Vernon, Norm Crosby, Stiller and Meara, and Tommy Cooper; the Ballet America; and Baby Opal, performing elephant.

Palace: Jimmy Durante is the ringmaster for the Palace circus show. Jimmy sings "Be a Clown," "Buffoons" and "When the Circus Leaves Town." Honorary ringmistress: young Anissa Jones of Family Affair. Acts include Roselle Troupe, ariel acrobats; Kay's Pets, animal act; Linon, slack-wire clown; Sensational Parker, swaypole performer; Great Rudos, performing elephants; Candy Cavaretta, trapeze artist; Hanneford Family, clowns on horseback.

Circus shows can be very dull or very entertaining, depending on the quality of the acts and how you feel about circuses (and clowns). Without seeing Palace, we really don't have any way of knowing which one this is, even though Jimmy Durante is always entertaining. However, Ed has a full lineup of acts, most of them well-known, and with both the McGuire Sisters and Lulu, he's appealing to all the age groups tonight. So let's go with Sullivan this week.

l l l

|

| As seen in Singer stores |

Continuing on this theme, Rod Serling is returning to televisison, "for at least one show. He's writing a script for NBC's Prudential's On Stage drama series. It'll be a political story tentatively entitled "Certain Honorable Men." That is, indeed, how it comes out when it's broadcast on September 12, with Van Heflin starring as a powerful but corrupt congressman, and Peter Fonda and Alexandra Isles as the staffers who discover the truth of his activities and turn on him. Although the soundtrack for this drama still exists, this is thought to be one of those "lost" broadcasts that so irritates historians like me. Having perhaps learned from his previous frustrations at with contemporary television writing, Serling here chooses not to focus on a specific issue, but on the values of the people who represent us in office. And of course we all know this won't be Serling's last go with television; he'll be back next year with Night Gallery.

There's also mention of Academy Award-winning actress Miyoshi Umeki joining the cast of The Courtship of Eddie's Father, a pilot for a proposed series on ABC starring Bill Bixby. That's one pilot that does indeed make the schedule, and it has a three-season run. One show that doesn't, apparently, come to fruition: the Singer Company is talking with the Beatles about an American TV apperance. As far as I know that never happens, but Singer does have a very successful series of music specials that they sponsor—including the Elvis Comeback Special.

l l l

Along with our regular fare, we've got some excellent movies airing on network and local television this week, led by a repeat of The Best Man (Friday, 9:00 p.m., CBS), Gore Vidal's savage 1964 story of presidential candidates vying for the nomination at their party's national convention. Judith Crist says that the movie "achieves near-thriller status with the almost unbearable tension building from a man’s reconsideration of his own moral values and the suspense dependent on how far a demagogue’s passions can carry him." Henry Fonda stars as the moral man who may not have the inner strength to be a leader; Cliff Robertson is his opponent, unscrupulous but with the qualities to be a decisive president; and Lee Tracy as the former president whose endoresement everyone values, but who has his doubts. It's well-made, well-acted, and well-written, and no wonder it shows up on by quadrennial list of favorite political movies.

Champagne for Caesar (Saturday, 9:00 p.m., KBHK in San Francisco) is a witty 1950 satire on television and quiz shows, featuring Ronald Colman as a polymath determined to break the bank on a quiz show; Vincent Price as the show's sponsor, whose refusal to give Colman a job spurs the revenge plot; and Art Linkletter as the show's smarmy host. Critics weren't all that high on it, but I've found it as a very funny take on an industry that deserves spoofing.

Sunday's movie classic is one of the most influential of horror films, 1941's The Wolf Man, starring Lon Chaney Jr. as the title creature (a character he'd reprise in four sequels), with Claude Rains, Ralph Bellamy, Warren William, and Bela Lugosi rounding out a top-notch cast. If you've already seen enough werewolves, you might prefer heading down to the Pecan Valley Country Club in San Antonio for the final round of golf's last major of the season, the 50th PGA Championship (2:00 p.m., ABC). At age 48, Julius Boros masters the sweltering heat for a one-shot victory over Arnold Palmer (who misses an eight-foot putt on 18 to tie) and Bob Charles; third-round leaders George Archer and Marty Fleckman finish another stroke back.

Also on Sunday: The 21st Century (4:30 p.m., CBS) looks at the medical and lifestyle advances that may make it possible to extend average life expectancy to age 100. It's a wistful hope, looking at it in retrospect; the latest statistics show that life expectancy in the United States has dropped for the second consecutive year. In 2019 it was nearly 79, but by last year it had fallen to just over 76; I wonder how much those supposed medical advances have had to do with it? And speaking of failed medical experiments, Jack Palance (right) stars in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (9:00 p.m., ABC), a Dan Curtis production that originally starred Jason Robards, but was interrupted by a strike (fancy that); when filming resumed, Robards was unavailable and Palance stepped in.

Monday gives viewers some tough choices, including the classics Damn Yankees (8:00 p.m., KRON, San Francisco), with Tab Hunter, Gwen Verdon, and Ray Walston; and The Quiet Man (8:30 p.m., KCRA, Sacramento), starring John Wayne, Maureen O'Hara, and Barry Fitzgerald. And if those don't provide enough star power, The Lucy Show (8:30 p.m., CBS) finds Lucy at a Hollywood premiere, with cameos from Kirk Douglas, Edward G. Robinson, Jimmy Durante, and Vince Edwards.

Remember how, when a network movie ran short, the network filled the remainng time with a short film? We've got some examples of that this week; on Tuesday, CBS follows the movie Mister Moses ("tastless idiocy," according to Crist) with "a preview of fall shows" that was probably an abbreviated version of this. (9:00 p.m.) Wednesday, ABC does something similar, following the 9:00 p.m. movie Ski Party (starring Frankie Avalon, Dwayne Hickman, and Yvonne Craig) with "highlights of 1967 college football games," including this showdown for #1 between USC and UCLA. What would they do nowadays to fill the time until the local news? Probably add more commercials—but I forgot; they don't show movies on network TV anymore.

On Thursday, Julie London and her husband, Bobby Troup, headline the monthly Something Special (9:00 p.m., KTVU in Oakland), with the Hi-Los and bandleader Jerry Fielding. That's up against the CBS Thursday movie Tickle Me (9:00 p.m.), with Elvis as an unemployed rodeo star. By the way, that doesn't fill up the entire hour and 55 minutes, so it's followed by "a behind-the-scenes look a the filming of Funny Girl, with Barbra Streisand.*" (Something like this.) And in case you're wondering why the movie slot was only 1:55, the final five minutes was filled by a political talk from presidential candidate Nelson Rockefeller.

*Spelled "Barbara" in the listings, but I've taken the liberty of making the correction.

l l l

Richard Long is the subject of Dwight Whitney's cover story, and he comes across not only as a successful actor, but a very nice man. He's known for his stints in the WB detective shows Bourbon Street Beat and 77 Sunset Strip, and he's now one of the stars of ABC's Western The Big Valley. Not only that, he's also honing his chops as a director, helming the first episode of the fourth season. He's described as "Cool, intelligent, bright!" by co-producer Arthur Gardner, who adds, "If we didn't need him so much as an actior, e'd make a fine director."

Long is known on-set for being calm, cool, and collected. Steady and dependable are words used to describe him, and nothing, but nothing, seems to get to him. He concedes it's an "insane" business, but says, "I have a great deal of respect for it. I see it as a job, a craft. That part turns me on," and Whitney notes that his directing success is a good thing for a man who's always been uncomfortable with the idea of stardom, which he sees as "frightening."

Throughout a life that's had its ups and downs, he's maintained that steadiness. His first marriage, to actress Suzan Ball, ended when she died of cancer after 14 months. She was diagnosed shortly after they started going together, but they married anyway. "We all lose, and you have to be prepared for that," he says. "You learn from it. You have to allow it to happen. There is a suffering period and life goes on again. His second, to acress Mara Corday*, has been stormy, but despite threats and divorce filings on both sides, they remain together and the marriage maintains a kind of rocky stability that lasts for the remainder of his life.

*Who appeared in the MST3K classic The Black Scorpion.

The Big Valley runs for four seasons; after that, Long co-stars with Juliet Mills in the much-loved Nanny and the Professor for a couple of years, followed by the short-lived Thicker Than Water with Julie Harris. Having a history of heart trouble, he dies of a heart attack in 1974, at only 47. But the closing quote from a friend seems to sum up his career and his life very well: "It is the nobility of being content to be exactly what you are."

l l l

MST3K alert: Eegah! (1962) A prehistorictype giant living in the desert falls in love with the teen-age girl who discovers him. Arch Hall Jr., Marilyn Manning, Richard Kiel. (Friday, 9:00 p.m., KMEO in San Francisco) Looking at the cast, you have three guesses as to who plays the prehistoric giant, and the first two guesses don't count. This movie was made the same year as Kiel's famous appearance in "To Serve Man" on The Twilight Zone; it's one of three appearances he makes on MST3K. Believe me, by the end of this one, you'll be rooting for him against the people he's supposed to be terrorizing. TV

July 21, 2023

Around the dial

Xt the Broadcasting Archives, we start the week with an intriguing look at how The Lucy Show almost wound up breaking new ground in television, and why the show didn't continue with its mildly feminist outlook.

One of my favorite underappreciated shows is The Rogues, about a merry band of con men (Charles Boyer, David Niven, and Gig Young), and at Christmas TV History, Joanna continues her "Christmas in July" series with Boyer making merry in the Yuletide episode "Mr. White's Christmas."

At Cinema Scholars, it's a look at the spy craze that became the in-thing on American television in the 1960s. It was fun for awhile, but from Batman to The Man from U.N.C.L.E. to Amos Burke, Secret Agent, camp took over and, one by one, many of them sank slowly into the sunset.

Jodie discusses one of the most difficult aspects of Dave Garroway's life at Garroway at Large, one that was also challenging to write about: Garroway's struggle with depression, and his ultimate suicide. This week she writes about how she tried to cover it with sensitivity and discretion.

John's series on The X-Files and the American Dream continues, and while his writeup of the episodes is very good, it's his exploration (as a non-American) of how the dream started out, and what it has become over the years, that adds significant value.

At The View from the Junkyard, we return to the world of The Avengers and "The Danger Makers," a 1966 episode in which we get a glimpse of the difficulties a war veteran has when returning home, and what happens when they try to create some danger for themselves.

Finally, the website The Hits Just Keep On Comin' celebrates 19—count 'em, 19—years, and as is custom, JB takes a look at some of his favorites from the past year. Congratulations, JB, and I hope you've got 19 more in you! TV

July 19, 2023

The Descent into Hell: "A Feasibility Study" (1964)

It is hard enough to find anyone who will die on behalf of a just man, although perhaps there may be those who will face death for a good man. —Romans 5:7

At the outset, the opening narration from the Control Voice tells us of the planet Luminos, a planet in a distant system. Earth scientists have concluded that the planet is too close to its sun to support life, but life exists there nonetheless, a strange and suffering form of life that now searches the galaxy for a planet with a healthy population—one that can be enslaved.

Meanwhile, a man prepares to drive to the office, while his wife lovingly chides him about spending too much time at work. Next door, another man, breaking off a continuing argument with his wife, seeks refuge at church, but finds his car will not start. Outside a mist has settled over the neighborhood—is it radioactive? Such are the mundane features of an everyday Sunday morning on Midgard Drive in Beverly Hills, USA, Earth, a neighborhood that is about to become the subject of a most unusual experiment—a feasibility study.

I

Ralph Cashman (David Opatoshu), a driven businessman, prepares to go to the office on Sunday morning—he has a "success compulsion," according to his wife Rhea (Joyce Van Patten), who wants him to at least have breakfast first.

Outside, he meets his neighbor, Dr. Simon Holm (Sam Wanamaker). Simon’s car won’t start, so Ralph offers to give him a lift to church. Simon’s wife Andrea (Phyllis Love) appears in the doorway; they hadn’t said good-bye, and she’ll be gone by the time he gets back. On the way, Simon confides to Ralph that he and Andrea are separating. They’ve only been married a year and a week, but Simon says it’s been "long enough to find out we made an honest mistake."

|

| David Opatoshu |

Back in the neighborhood, Simon returns to find Andrea still home; she couldn’t call a taxi because the phone is out of order. It is obvious that Simon doesn’t want Andrea to leave, and he renews his plea to her to stay, but she is adamant. She won’t stay if Simon won’t let her have "some part of my life to live my own way." If you really love someone, you should be able to "understand another person’s heartbeat, even if the rhythm is different from yours." "I can’t live with you if life has to be lived according to your prescriptions," she tells Simon. "I can’t! No matter how benevolent or secure you’d make it, it’s slavery!" Simon replies that he’s not trying to run her life; "I just don’t want you wandering around the world with your camera and your typewriter worrying about everybody else, when I need you here, always, at home."

Their argument is interrupted by a scream from Rhea. Someone is walking up the sidewalk to her front door. When the figure collapses, Simon sees that it’s Ralph, his face and hands covered by grotesque skin eruptions, similar to those on the beings that surrounded Ralph’s car. Ralph warns Rhea, in a ghostly voice, that she must not touch him, and adds, "We’re not on Earth." His body then vanishes.

They next see a figure going into the garage. Rhea is sure it must be Ralph, but Andrea tells her it wasn’t even a man. He goes to the door, but a voice from inside the garage warns him not to come in. Simon tells Andrea to get the car in case they need to take whoever it is to the hospital; then, talking through the door, asks if he needs help or is hurt. The voice replies that he’s not hurt physically, just afraid. "I came through the shield," the voice says. "I’ll be punished if I spoil the experiment." He’s only 16, the voice says, "I’m almost an old man." He says he’ll go back, but they can’t see him. Simon tells Rhea to go back indoors. Meantime, Andrea waits in the car she was going to use to drive Ralph to the hospital. When the being emerges, he heads for the car and tells Andrea to take him back, "or I’ll touch you." Andrea speeds into the cloud, and Simon runs after her, disappearing from sight.

Emerging on the other side, Simon finds himself in the same unearthly setting that Ralph entered earlier, surrounded by the same creatures—ponderous figures, bodies encased in the same kind of rocky terrain as the planet’s surface, almost becoming part of the background. Simon sees Andrea suspended in a tube-like cylinder, before he is led in front of some kind of council. One of them, referred to in the credits as The Authority (voice of Ben Wright, physically played by Robert H. Justman), tells him that their entire neighborhood, six square blocks, has been teleported to the planet Luminos.

II

There’s an interesting footnote to this, as writer Ted Rypel observes: the fact that the Luminoid children have apparently rebelled, necessitating the Luminoids’ mission to abduct and enslave the Earthlings. Does this imply that the desire for freedom isn’t the sole province of humans, that it’s somehow inherent in all sentient beings? Or does the appearance of the Luminoid youth, curious to see what exists outside the foggy barrier, suggest that the young are alike all over, rebelling against their parents and against the system, nothing more than a Luminoid Rebel Without a Cause?

III

|

| Sam Wanamaker and Phyllis Love |

"That’s the whole bright mystique of life, choice," Simon tells her. "Maybe that’s what the soul is. Choice."

"Can we live with the loss of it?" Andrea asks.

"Perhaps," Simon replies. "But I think it would be better to die trying to win it back."

Simon decides they must alert the rest of their neighbors to what has happened, and set up a meeting in the church, to discuss what they must do. Andrea tells Simon she’ll meet him there, and after he leaves, she looks at herself in the mirror, at the first sign of eruption that’s started to break out on her shoulder.

As everyone gathers in the church, Simon looks for Andrea, but the priest, Father Fontana, assures him that she will show up. To the group, Simon now explains what the Luminoids plan for them. As Father Fontana recites The Lord's Prayer, someone starts pounding at the door. Simon, thinking it is Andrea, implores the two men guarding the door to let her in; when they refuse, Father Fontana approaches them and raises his hand, palm facing the doors as if in the form of a blessing, and the men part. Outside is Ralph, fully enveloped in the disease. The priest moves to take Ralph in his arms, but is held back by Simon; the rest shrink back in fear and horror.

Ralph stands in the doorway: alone, weeping, utterly desolate. Rhea runs to him, but Ralph will not let her touch him. We see that Andrea is also there, standing behind Ralph. She now admits to Simon that she, too, has been infected, just from the time she spent in the car with the boy, breathing the same air.

Simon then turns back to the rest, and bluntly tells them there is no way of escape, no way back to Earth. Their future is as slave labor. They don’t have to suffer the same fate as Ralph, not as long as they remain in their homes and don’t travel more than six blocks in any direction; even if some, like Andrea, catch the disease through the air, enough of them will survive to make the experiment feasible. And then the Luminoids will teleport the entire population of Earth to the planet to be enslaved. "We will live in labor camps," he says, "we will toil and sweat and die in controlled areas."

But we have a choice, he reminds them. Human choice. They can let the Luminoids know that they will not simply stand by while the entire human race is enslaved. They can choose to voluntarily expose themselves to the disease, to become what the Luminoids are. "My wife has already been infected," he tells them. "I’m going to take her hand. Will someone take mine?"

After a moment’s hesitation, Andrea stretches out her hand, which is taken by Simon. Rhea then takes Simon’s other hand; her free hand, in turn, is grasped by Father Fontana, and in turn the others, one by one, form a human chain, hand in hand. A chain forged by love, and a resolution to thwart the Luminoid plan.

A final image shows the crater that marks where the Midgard neighborhood once stood. An official sign has been posted telling people not to enter the area due to threat of possible radioactive dirt or rocks, and asks anyone with knowledge concerning the disappearance to contact the police. The Control Voice advises us that the Luminoid feasibility study has concluded. "Abduction of human race: infeasible."

IV

Watching the first half of "A Feasibility Study," a viewer might reasonably wonder why I’ve chosen to include it in this series. It unfolds as a mystery, a domestic drama, a science fiction story complete with alien monsters. A horror story to be sure, but not the same kind of horror that we’ve witnessed here.

That is the way it is, the way events sneak up on you until, before you know it, you find yourself in the middle of it.

Of course, what "A Feasibility Study" is really about is slavery, among other things, but a unique and most seductive kind of slavery, that of the velvet fist. As the Authority tells Simon, "You will be happy. Your lives here will be comfortable and secure, and you will be free to worship and love and think as haphazardly as usual." Kind of like You will own nothing, and you will be happy, don’t you think? I can’t remember who said that, but I’m sure you know what I mean.

The power of Joseph Stefano’s script is that the horror of slavery is never seen. There are no scenes of tortures, of beatings, of vengeful masters whipping helpless slaves trying to escape. These masters are literate, even eloquent, not the monsters of "1984" and "Darkness at Noon." And talk about accommodating—or at least practical, for as Simon tells his fellow humans, we are no good to them dead. No, I think Stefano trusts us to understand this; he never even bothers to explain what type of work the slaves are to carry out, and in truth it makes no difference, for the kind of slavery he’s talking about doesn’t require work; it merely requires people to let themselves be led around like sheep—unthinking, uncaring, unfeeling.

Where "A Feasibility Study" makes its point is in presenting the alternative to slavery, what David Schow, co-author of The Outer Limits: The Official Companion, describes as "vivid sketches of the human spirit." It is what the Luminoids, for all their advanced knowledge, could not anticipate: the power of caring, of loving, of sacrifice; of overcoming fear and uncertainty; most of all, the power of choice. For Stefano, human beings by definition cannot be sheep, are incapable of being sheep, as long as they have free will and an intellect, as long as they are capable of choice. Of course, if one chooses to be a sheep, there is nothing stopping them.

(Incidentally, about the name of the street everyone lives on, Midgard Drive: According to Norse legend, Midgard describes "the world inhabited by men," and J.R.R. Tolkien derived from it the term Middle-earth. Midgard was also said to be surrounded by Jotunheim: the world of the hostile giants.)

"A Feasibility Study" was the ninth episode in the production cycle, wrapping up in August 1964, but it would not air until eight months later, on April 13, 1965, as the series’ 29th episode. The delay was unwelcome, but not exactly unexpected; "There was enough thinking going on in The Outer Limits to worry people," recalled the show’s creator, Leslie Stevens, and approval from the network’s Standards and Practices department was unusually slow in coming. ABC was particularly nervous about the ending, which network censor Dorothy Brown read as condoning mass suicide. "She saw the act of martyrdom as a negative gesture rather than a noble one," Stefano said. "But I probably proved my point when ABC saw the finished film, with everyone joining hands. It was very moving and inspirational, and that’s when they approved it."

A few words about the performances of the principals in the cast. Sam Wanamaker and Phyllis Love as Simon and Andrea Holm, display a quiet vulnerability that, once they reunite, turns to strength and courage. David Opatoshu* and Joyce Van Patten, as Ralph and Rhea Cashman, inject their brief scenes together with the comfortable affection borne of a successful marriage; Opatoshu’s reappearance as the infected Ralph is simply heartbreaking, and Van Patten’s response is both touching and inspiring. Ben Wright, providing the voice of The Authority, is appropriately superior and distainful; Frank Puglia, in the small but not unimportant role of Father Fontana, projects a quiet power and spirituality, particularly in the closing scene.

*You’ll remember him from the earlier essay on the Star Trek episode "A Taste of Armageddon," where he played a considerably less honorable character.

The unsettling atmosphere of the planet Luminos, its oppressive fog and darkness contrasting with the everyday normality of the human neighborhood to create a growing sense of impending doom, is portrayed in stunning, glorious black and white by cinematographer John Nickolaus; the poignancy of the episode’s final scene, as the humans commit to their heroic sacrifice, is enhanced by the lovely, heartrending music of Dominic Frontiere—and, surprisingly, it wasn’t even composed specifically for the episode, instead consisting of musical cues composed for other Outer Limits episodes.

While critics were divided on the merits of the story, "A Feasibility Study" struck a note in viewers that made it one of the most-remembered episodes of the series, a profoundly moving meditation with a singularly memorable ending. If there isn’t a moment in it that causes you to think about your life and the lives of your family and loved ones—well, there’s something about you that just isn’t human.

V

The climactic scene of "A Feasibility Study" takes place, appropriately, in a church. It is there that we see the symbols of religion most clearly: the candles, the statues, the Rosary beads. And at the heart of it, looming ever-present in the darkness as Simon makes his impassioned plea, the symbol of the ultimate sacrifice, the Crucifix.

This is not the first time we’ve discussed an act of self-sacrifice here; "Dialogues of the Carmelites," "Murder in the Cathedral," and "The Obsolete Man" all end with the protagonists accepting their deaths with courage, defiance, and faith—a reminder that death is not the end of life.

But even if we were in a studio stripped bare of any decoration, we wouldn’t be able to overlook the religious aspect of this drama, and I can’t help but wonder if this caused any of ABC’s discomfort, because it leads to some uncomfortable questions, the biggest of which being the nature of free will.

Free will is one of the greatest mysteries of life. Why do we have it? The standard answer is that we were given it in order that we might choose good over evil, right over wrong, things you probably learned in Sunday School.

|

| Joyce Van Patten |

Whether we like it or not, free will is a gift to us, one that asks of us that we exercise it thoughtfully. It tests our mettle, shows what we’re made of, appeals to both the best and the worst in us. Most of all, it asks us to choose. "That’s the whole bright mystique of life, isn’t it?" Simon muses. "Choice. Maybe that’s what the soul is: choice." Those people I mentioned above all had something in common: they were given a choice, and their choices were driven by their faith.

For the Carmelites, they chose to offer their lives as martyrdom, moved by a faith that, by being persecuted for their beliefs, the fire of hatred that inflamed the revolution would become uncontrollable and would wind up consuming itself and burning out, leading to divine graces for the people and for France. And especially for Blanche, the young sister who had fled in order to save her life and then had returned so that she could give it up, the knowledge that she would no longer be ruled by fear.

For Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury locked in a struggle with King Henry II, he has only to submit to the authority of the king to avoid death; but having returned to England from France, and the protection of King Louis VII, he chose to remain in an unlocked Canterbury Cathedral despite the pleadings of his monks to either flee or barricade himself inside, and instead faced the knights he knew would assassinate him.

For Romney Wordsworth, the obsolete man, his choice was to accept death as an act of resistance, echoing the words of St. Paul, "Death, where is thy sting?" And, as he sat in his room reading from his banned Bible and honoring a faith he refused to renounce, he might have hoped that the people would realize that the emperor had no clothes, that the Chancellor was driven by fear just like they were; and that therefore, they could defeat him, bring down the State, and show that no man is obsolete.

All of them faced execution as punishment for their choice. By contrast, the deal offered to the humans on Luminos seems to be a pretty good one. The Luminoids "don’t intend to harm us," as Simon points out. "They want us strong and well. They need our strength." True, you could die just from breathing the same air, but we can chalk that up to the same risks we face every day; after all, getting out of bed in the morning is a risk, we often remind ourselves. Whatever it is that they have to do as slaves to the Luminoids, one could envision living a good life, or at least a tolerable one. Get up in the morning, go off to work, come back in the evening, have dinner, catch up with the wife and kiddies, and go to bed. You can even go to church on Sunday! And anyway, aren’t we all just wage slaves already, working for The Man every night and day?

But the Carmelites, Becket, Wordsworth, the Luminoid slaves: they’re all human beings. And, as Simon tells them, we can choose.

We can choose.

In a way Dorothy Brown was correct; without that faith, and without that freedom to choose, there is no sacrifice: it simply amounts to mass suicide.

VI

I’ve written about fear many times in this series; it’s a theme that runs through most of these stories. Fear is the greatest destructive power on Earth, one of the most fearsome human emotions, for those who know how to use it. Fear of authority, fear of reprisal, fear of being a non-conformist; fear of the unknown, fear of the future. The totalitarian state is constructed on fear; it is what the overlords count on—what they depend on—to remain in power. It is also what drives them; fear of the loss of power.

For fear to be overcome, it first has to be acknowledged, recognized for what it is. The phrase "Be not afraid," or variations thereof, appears more often in the Bible than any other admonition. The great entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. once said that "reality is fear of the unknown waiting around the bend." In the British science fiction series Doctor Who, the title character accepts death as the price for overcoming fear; "I had to face my fear," he says. "That was more important than just going on living."

In "A Feasibility Study," the Luminoids are banking on the human fear of death, and the willingness to do anything to avoid that death. The Authority astutely sized up the Earthling as "vain fleshmen who love their bodies above all else that nature has given to them," and concludes that, "you will obey. At the threat of our touch, you will obey." And in truth, it’s hard to blame them for coming to that conclusion. After all, look at what the human race did in the name of a virus that had a survival rate in the upper 90s. They subjected themselves to an untested "vaccine" without regard to the possible side effects, closed down society and business, demonized anyone who "questioned the science."

But that’s not all. Over the last few decades, humans have become so sensitive to any kind of risk that it’s almost pathological. From food allergies to antibacterial soap, fear and disease lurks around every corner. Understand that this isn’t to demean or diminish those who actually suffer from such maladies, but one has to wonder sometimes if the preventative actions we take aren’t, in fact, responsible for the ailments in the first place; a basic exposure to germs, for example, is necessary to the development of a functioning immune system.

No, for all the bluster about how savage humans are at heart (a theme of many a science-fiction story, including ones seen on The Outer Limits), we’re actually quite timid when it comes to it, so risk-averse that one wonders what value there is to a life that doesn’t allow for taking chances. I’m fond of quoting Harry Reasoner, the legendary television newsman, who wrote that "The idea of trying to outguess life, to avoid everything that might conceivably injury your life, is a particularly dangerous one. Pretty soon you are existing in a morass of fear." Life asks a great deal of man in exchange for what it provides, but "if life asks him to cringe in front of all reasonable indulgence, he may at the end say life is not worth it. Because for the cringing he may get one day extra or none; he never gets eternity."

So the Luminoids could hardly be blamed for believing that their human captives would accept slavery rather than suffer the consequences. They would have looked at this as manna from heaven, absolute proof that they could exploit that fear into creating a slave race.

But there is one thing that can overcome fear, and that is love. It is the equalizer, the great healing power, because without love there can be no sacrifice, not really. And a very interesting thing about "A Feasibility Study" is that it is about love as much as it is fear. The first half of the story highlights the absence of love, or at least the relegation of love to a lesser status. Despite their words, it’s obvious that Simon and Andrea love each other, but they won’t let that love breathe through layers of ambition and disappointment and cynicism. It’s only when they’re confronted by something that is bigger than either of them that they realize how only by coming together can they face it.

And if the first part of the story is about the absence of love, then the conclusion shows us what happens when love is allowed to overcome fear. It’s what happens when Simon and Andrea support each other and, in doing so, gain the strength to defeat it. It’s what happens when Father Fontana approaches the church doors and, with a simple gesture, is able to move aside the two men barring entrance to the church, reminding them that the church closes its doors to no one. It’s what happens when, in one of the most moving scenes in the drama, the weeping David is comforted by his wife Rhea, who is not afraid to go to him.

Another thing that occurs to me: you might have noticed than when Father Fontana opens the door and finds the infected David standing there, his first instinct is to reach out to him until he is restrained by Simon. I don’t know if Joseph Stefano or anyone involved in makeup for the show had this in mind, but the effect of David’s appearance there evoked, at least in me, an image of someone infected by leprosy—a disease which, similarly, caused people to recoil in horror for fear of contamination. And I thought of Fr. Damien, the Catholic priest who treated the lepers of Molokai and eventually was infected himself; it is said that in his first sermon after the diagnosis, instead of his usual greeting of "My fellow believers," he began, "My fellow lepers." A small moment, perhaps.

Perhaps the most inhuman thing the human race did during the virus scare was to intentionally isolate themselves from each other, to cut off the most vulnerable from human companionship and contact. How many times we heard of those not allowed to see their loved ones in a hospital or nursing home, not able to furnish them with companionship, not able to be with them in their last hours of life. They not only reacted out of fear—fear that had been imposed on them—they themselves stoked that fear, added to it until it became hysteria.

That contact, the human touch and the love that comes with it—so simple, and yet we deliberately, willingly removed it from use. There was a lot of talk thrown around at the time about caring for others, about this isolation being an act of love. In some specific cases, there may well have been a medical justification for it. But make no mistake—this was no act of love. There was no love involved in it.

VII

Death does not mean that life has ended, but merely changed.

There is a tendency, in all allegorical stories, to view them as something of a commentary on current affairs, a way to offer a thought-provoking or unpopular take on something that’s part of the zeitgeist. In this case, one would be forced to look at the threat of communism or the fight for civil rights as inspirations for "A Feasibility Study." (Ironic, considering that proponents of civil rights were often accused of being part of the communist threat. And certainly that possibility can’t be ignored.

However, the issues that Joseph Stefano explores—freedom, choice, love, fear—go far what would have been necessary to make a simple plea for tolerance. For that reason, I’m convinced that Stefano did not want the episode to be seen purely through the lens of contemporary events. For him, the idea of martyrdom, the voluntary sacrificing of life in order preserve the human race, seems to have been his main interest, and there’s no way to fully understand and appreciate that aspect without looking at everything else. And those are timeless themes, applicable to any era.

When I rewatched "A Feasibility Study" episode for this essay, I couldn’t help thinking about the passengers of United Airlines Flight 93, the flight that crashed in Stonycreek Township, Pennsylvania on September 11, 2001. You remember: the passengers, having learned from their phones of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, fought back against their hijackers, forcing the plane to crash well short of its intended target. Like the humans held captive by the Luminoids, they understood that they could not escape, that there would be no return to their former lives, their friends and loved ones.

But those passengers understood—their actions indicate they must have understood—that even though the fact of their deaths could not change, the meaning of their deaths could, and would. They would die at the hands of their captors, or they would sacrifice their lives to prevent their captors from accomplishing their goal, and taking yet more innocent lives. Either way, they would be dead—but nothing else would be the same. One can choose to die as a slave, or to die as a free man.

We can choose.

There is one major difference in these sacrifices. The whole world would know soon enough about what happened on Flight 93, and that their rebellion, directly or indirectly, would lead to the crash of the plane, the failure of its mission. The sacrificial act made on Luminos, on the other hand, will go unknown by the billions on Earth, including many who may not have merited it. They will supply no encouragement; they will raise no standard under which others can choose to fight back, there will be no shrine constructed in their honor. In fact, were you to ask Simon, he might tell you that this is the way it had to be, for it would mean that their rebellion had succeeded, that the continued teleportation of Earthlings had been found to be unfeasible, that no one on Earth would ever know about it.

And while those on Earth might remain ignorant of what happened, we can observe that there is a lesson to be taken from it all, which is that freedom is something intrinsic in the human spirit. It may lie submerged, deep in the recesses of the psyche, perhaps for generations at a time; nevertheless, it exists, waiting for the moment when it will be called on, when a spark will bring it to life.

"It is for freedom that Christ has set us free," St. Paul writes to the Galatians. "Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery." The apostle was writing about the slavery of sin, but there is more than one kind of slavery, just as there is more than one kind of freedom. The Luminoids did not understand that, but we do, because humans have always had to fight for their freedom.

We can choose.

Some people look at the ending as sad, depressing, but that’s not how I see it, not really; in fact, I’m rather encouraged by it, because it suggests the indominable spirit of the human being, the desire for freedom, and the ability to love. Even in these times, the times in which we live today, it’s comforting to think that this spirit is ingrained in us, even when we doubt its existence. I think it’s natural to wonder if, when put to the test, we’ll really respond the way we hope we would, we’ll make the right choice.

The Luminoids would have accused their would-be slaves of having chosen death, but in reality they chose freedom. They chose life. Possibly—just possibly—we will, too. TV

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)