Like many of you, I rue the day when "fake news" entered the vocabulary. It may have been a good idea at the time, but that time is long past, and the term has been so overused, so distorted, that it no longer means anything at all. But whether or not there is such a thing as "fake news," the idea that we're not getting all the news, all the time, isn't a new one. This week's lead article comes from Nicholas Johnson, an FCC commissioner who agrees with network heads that censorship is a serious problem in America, but he adds that the problem doesn't come from the government, but from the networks themselves.

Johnson, who was appointed to the FCC by Lyndon Johnson and will be reappointed by Richard Nixon, offers several examples: NBC cutting off Robert Montgomery when, during a discussion with Johnny Carson on Tonight, he mentioned a CBS station being investigated by the FCC; Joan Baez being prevented from giving her political views while on The Smothers Brothers Show; and the subsequent cancellation of that show. "Sure, there's censorship," Johnson says. "But let's not be fooled into mistaking its source." Network officials, he writes, "are keeping off your television screens anything they find inconsistent with their corporate profits or personal philosophies."

The success of the American experiment, Johnson says, is "the concept of an educated and informed people." Today, that information comes from three networks and two wire services, and these broadcasters "are fighting, not for free speech, but for profitable speech." Case in point: a Febuary 10, 1966 Senate hearing on the Vietnam War. "Fred Friendly, who was president of CBS News at the time, wanted you to be able to watch those hearings. His network management did not permit you to watch. If you were watching CBS that day you saw, instead of George Kennan’s views opposing the Vietnam war, the fifth CBS rerun of I Love Lucy." Friendly quit CBS over the matter; his subsequent book, Due to Circumstances Beyond Our Control, begins with the quote, "What the American people don't know can kill them."

Johnson accuses the media of being in thrall to the big corporate dollars that sponsor their programs. The tobacco industry spends about $250 million a year on radio and television commercials, but "the broadcasting industry has been less than eager to tell you about the health hazards of cigarette smoking." The auto industry spent more than $361 million on advertising in 1964 alone, but the media was silent when it came to the 50,000 highway deaths yearly, virtually "all" of which could have been saved if cars were designed properly. Television news basically ignored recent Senate hearings on truth in food packaging—is it a coincidence that 52.3 percent of TV's total advertising comes from the top-50 grocery-products advertisers? And as for the "law and order" refrain that's swept the news, who knew that much of that crime is of the white-collar variety? "A single recent price-fixing case involved a 'robbery' from the American people of more money than was taken in all the country's robberies, burglaries and larcenies during the years of that criminal price fixing."

And there's more: Black lung disease is on the rise, the life expectancy of the average adult American male is going down, natural-gas pipelines are exploding, color television sets are emitting excess X-ray radiation. Says Johnson, "Note what each of these items has in common: (1) human death, disease, dismemberment or degradation, (2) great profit for manufacturers, advertisers and broadcasters, and (3) the deliberate withholding of needed information from the public."

Paraphrasing Bob Dylan, Johnson says that "The 'Silent Screen' of television has left you in ignorance as to what it's all about." And unless and until the media allow all viewpoints to be heard, popular as well as unpopular, there can be no true freedom; as a recent Supreme Court decision declared, "Freedom of the press from governmental interference under the First Amendment does not sanction repression of that freedom by private interests."

(By the way, pharmaceutical companies paid out $1.68 billion on ad campaigns last year. Just thought you'd like to know that.)

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Johnson admits that there are no easy answers, but as an FCC commisioner, he feels as if someone has to speak about these issues. "And all I’m urging is that, when in doubt, all of us —audience, networks and Government —ought to listen a little more carefully to the talented voices of those who are crying out to be heard." "I would far rather leave the heady responsibility for the inventory in America’s 'marketplace of ideas' to talented and uncensored individuals—creative writers, performers and journalists from all sections of this great country—than to the committees of frightened financiers in New York City. Wouldn’t you? I think so." He's glad, he concludes, that the networks have raised the issue of censorship. "I hope they will permit us to discuss it fully."

l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era. This week, Cleveland Amory presents his annual Amory Awards for the best in television over the past year. There isn't anything particuarly clever or witty about them, just a straightforward recitation of the winners—or co-winners, as Amory borrows heavily from the year's Acadamy Awards, which saw a tie for Best Actress between Katharine Hepburn and Barbra Streisand. (Talk about the devil and the deep blue sea.)

At any rate, since it's the bon mots that we usually tune in for, I'm afraid this is going to be rather dull, except as an indicator of what shows were really big back then. And some are good reminders of shows we don't talk about often here, for instance the co-best comedies, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir and Julia, each of which won additional awards as well: Mrs. Muir's Hope Lange and Julia's Diahann Carroll share best actress in a comedy, while Edward Mulhare wins best actor in a comedy, and Lloyd Nolan takes best supporting actor in a comedy. Raymond Burr of Ironside is best actor in a drama, while his co-star Barbara Anderson shares best actress with Mission: Impossible's Barbara Bain. The supporting actor and actress drama awards go to Leonard Nimoy (Star Trek) and Joan Blondell (Here Come the Brides), and the comedy supporting actress is Kay Medford of That's Life. The rest of the best show winners are shared as well; drama belongs to Ironside and Mission: Impossible, the musical-variety winners are This Is Tom Jones and The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, and the talk-show host winners are Art Linkletter and Dick Cavett.

There are a lot of winners here, to be sure; either Cleve couldn't make up his mind, or he was really milking that joke about co-winners—milking it a little too much, if you ask me. But then, not every column can be a winner, or even a co-winner, can it?

l l l

America's got moon fever, baby! The Apollo 11 launch is scheduled for next week, and TV's gearing up for coverage of the great adventure with a handful of specials. On Sunday, The 21st Century (4:00 p.m. PT, CBS), has "Stranger Than Science Fiction," a look at how yesterday's sci-fi compares to today's reality, including movie depictions of space travel. One of those movies may well be First Men in the Moon (Wednesday, 9:00 p.m., KOVR in Sacramento), based on H.G. Wells' classic about a trip to the moon in 1899. NET has a pair of science-orieted programs: Tuesday, John Fitch's Science Reporter (11:30 p.m., NET) welcomes Dr. Wernher von Braun, director of the Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, who discusses space flights beyond the Apollo program. That's followed on Wednesday by Moon Research (10:00 p.m.) with Nobel Prize winner Harold Urey, one of the scientists who'll be evaluating the lunar samples brought back by the astronauts. NBC's Today Show has reports scheduled for Wednesday, Thursday and Friday mornings (7:00 a.m.) And maybe it's just a coincidence, but the KTXL (Sacramento) movie on Tuesday night is Dangerous Moonlight. (11:00 p.m.) It has nothing to do with space travel, but doesn't the title fit in well? By the way, if you want to see what television did with the epic flight, we covered that here.

The Apollo pre-coverage highlights a week that also includes the Wimbledon tennis finals (Saturday, 9:30 a.m. and 2:00 p.m., NBC). The early program is same-day coverage of the men's final, in which defending champion Rod Laver defeats fellow Australian John Newcombe for his fourth Wimbleton title. Laver is on his way to winning the Grand Slam for a second time, the only man to do so; no man has done it since. The afternoon coverage features the women's final, which was played Friday afternoon; Brit Ann Jones upsets American Billie Jean King in the final to become the first British champion since 1961. Incidentally, TV Guide refers to this as the "Wimbledon Open," which sounds cumbersome (as well as incorrect), but it's probably done to specify that this is the second Wimbledon open to professionals as well as amateurs; pro players on both the men's and women's side were banned from the Grand Slam championships until 1968.

A few other shows of varied interest:

- Meet the Press (Sunday, 1:00 p.m., NBC), with guests Senators George McGovern (D-SD) and Harold Hughes (D-IA). Why it's interesting: the two chair the Democratic Committee on Party Structure and Delegate Selection. Thanks to their liberalization of the delegate selection process, including more women and minorities, Senator McGovern is able to capture the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination, becoming the sacrificial goat to Richard Nixon's landslide victory.

- The Ed Sullivan Show (Sunday, 8:00 p.m., CBS). Tonight, Ed's guests are Gordon MacRae, Lainie Kazan (right), comies Jackie Vernon and Charlie Manna, singer Bobby Vinton, the Sugar Shoppe, magician Al Koran, and Valente and Valente, balancing act. Why it's interesting: The Hollywood Palace is off for the summer, replaced by Johnny Cash, so this was our only chance to see what Ed has in store; pretty good lineup, I think.

- Star Trek (Tuesday, 7:00 p.m., NBC), in which a beautiful woman removes Spock's brain from his skull. Why it's interesting: It isn't, which is what makes it unusual. "Spock's Brain" is generally considered by many Trekkers as one of, if not the, worst episode of the series.

- NET Playhouse (Thursday, 7:00 p.m., NET) presents "Trapped," the story of a young man whose brushes with the law work against him when he's accused of a murder he didn't commit. Why it's interesting: It's written by Georges Simenon, creator of the famed Inspector Maigret stories, although Maigret does not feature in this, one of Simenon's "psychological dramas."

- Dead Ringer (Thursday, 9:00 p.m., CBS), starring Bette Davis in a dual role; she kills her twin sister, only to find out that sis's lush life is more dangerous than she thought. Why it's interesting: Judith Crist praises Davis, who "gives her all, in doubles yet." It's also an example of an increasingly rare occurrence on prime-time network television: a black-and-white movie.

l l l

Kent McCord is the cover story this week, and he talks with Burt Prelutsky about how his attitudes toward the police have evolved since he started on Adam-12. He should have been excited, he acknowledges, to co-star in a TV series at the ripe young age of 26, a series with a good chance for success, created by one legendary television figure (Jack Webb) and co-starring another (Martin Milner), but he still wasn't happy. "I just don't like cops," McCord says. "I never had much trouble with them—just the usual kid-cop experiences, like being stopped and being asked where I was going—but they always seemed to be rousting peole for no good reason. They never seemed to be there when you wanted them, and always around when you didn't want 'em."

Things started to change when, according to McCord, he and Milner did some on-the-job training with real LAPD officers to get the hang of things. "I spent 14 nights riding around in a prowl car with a young officer named Mike Watters. It changed my attitude. I got to see the other side of the picture. You see, I had real qualms about glamorizing cops on the show, but riding around on patrol that way helped me get over that. A policeman, you discover, has to put up with a hell of a lot of abuse. A man in any other line of work would nail a guy who laid that kind of abuse on him. I know I would." Watters remembers how it went. "[O]on the second night we went out on a drunk call, and the drunk tried to kick Kent in the face. I think that's when his attitude started to change—when he began to really see what we're up against," he recounts. "I started to think of him as a partner, who'd do what he could to protect me—even though he didn’t carry a firearm."

McCord's connection with the show goes back to his appearance in the Dragnet revival, a set-piece story involving only Webb, Harry Morgan, and McCord. His performance was not forgotten ; says producer R.A. (Bob) Cinader, "When it came to casting Adam-12, it took us 10 seconds to make our decision. Jack had a real thing about Kent." McCord, says Webb, "has all the attributes of a big star." Working on Adam-12 has been an eye-opener for McCord in more ways than one, as Milner points out. "Kent's come a long way this season. He’s much looser now than he was in the beginning. You have to realize that he’s probably done more acting this year than he did in his entire career up to this show."

He's frustrated by the slow development of his character Jim Reed—he'd like him to be more active, reflect more self-assurance—but officers tell him he's doing it just right, that it's the way they were when they were rookies. He's glad that the show is starting to show things like it really happens out there, and adds, "I think it's a mistake that we don't have more violence in the show." And he admits he's still a bit reluctant to be seen as an advertisement for the police; he knows that his performance has made younger people consider law enforcement as a career when they might not otherwise have done so. "I don’t want to be a propagandist for anything but my own feelings, and, hell, I don’t want to be a cop. But I’m an actor and it’s just a job."

Kent McCord goes on to a long career in television and movies, and almost wound up playing a police officer one more time; Jack Webb was planning to make Jim Reed Joe Friday's partner in a new Dragnet series, but died before the series went into production. Now that's something I would have enjoyed seeing.

l l l

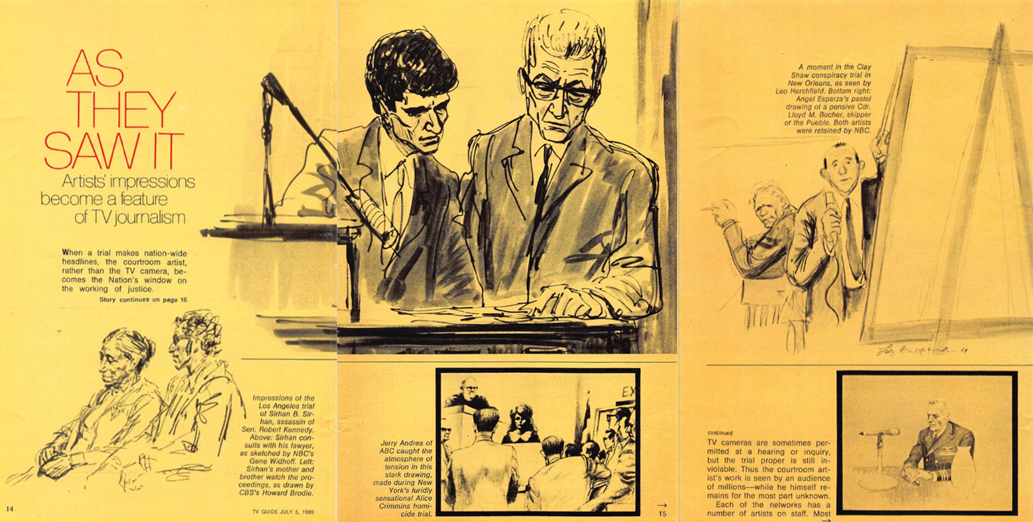

I know this may be hard for you to believe if you're one of our younger readers, weaned on dedicated real-life channels like Court TV, but there was a time when television cameras weren't allowed in courtrooms. Not only that, but in the wake of several court decisions on media coverage of trials (notably Sheppard v. Maxwell), still photographers were mostly barred as well, meaning that the most important person in the courtroom, at least as far as the networks are concerned, is the courtroom artist.

The artist deals in more than just a likeness; sometimes they're barely more than an outline, lacking even the detail seen in graphic novels. The artist has to capture the intangible—the drama, the gravitas, the history, the atmosphere filling the courtroom and spilling out into the news coverage. Lacking pictures or video, the sketch needs to convey all of this, and in the most economical way possible; Ben Blank, ABC's director of graphic arts for news and public affairs, lays out the job description. "They must be able to work in different styles, appropriate to the trials they're covering. We don't want anything too arty, because this is a reporting job—the artist is really just a stand-in for the TV camera. A good memory is also important, because some judges will allow artists in court to observe only, and will insist that the drawings be made outside the courtroom." It is, in a sense, a theater of the mind, not unlike radio when it comes to letting the imagination do the heavy lifting.

Below are sketches from some of the more recent trials of note: Sirhan Sirhan, on trial for the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy; Clay Shaw, on trial for consipiracy in the assassination of John F. Kennedy; the court martial of Lloyd Bucher, commander of the U.S.S. Pueblo; Alice Crimmins, on trial for the murder of her two children, ages five and four.

Few, if any, trials go without television coverage today (the last regular haunt of the courtroom artist might be the Supreme Court), and I think that's worked to the detriment of justice. Not because the lawyers or witnesses or judges are playing to the camera, though that certainly happens. (See: O.J. Simpson trial.) No, I think the problem is that the mystique, the grandeur of justice, is lost when it's filtered through a video camera. A still photograph can approach it, but even there it's destined to fall short. Modern courtrooms don't much look like temples of justice, to be honest; they more closely approach hotel conference rooms, kind of dull and boring, hardly the stuff of Perry Mason. With the courtroom artist, however, all the background noise is removed. You're focused on the defendant, the prosecutor, the spectator looking on, and you read everything in their faces, in what you see and what you don't see.

That's what I meant by that analogy to radio; in this world, the world of the artist, there's an inherent mystery at work, one filled in by the mind's eye. Maybe, just maybe, it would help us take it all just a little more seriously. Whether it deserves to be or not. TV

I keep thinking that we're living through Max Headroom. Nowadays Edison Carter would have had to publish his journalism on Substack or Medium and make his actual living doing something else.

ReplyDelete