January 31, 2022

What's on TV? Monday, February 5, 1968

It's the last primetime before the start of the Olympics, but I'm drawn to KTCA's Folio at 9:30 p.m. It's a program on theater, hosted by Warren Frost, who taught at the University of Minnesota and served as artistic director of the Chimera Theater in St. Paul. You might recognize him either from Slaughterhouse Five (which was filmed in the Minneapolis), or from his appearances in Twin Peaks. That, incidentally, was co-created by his son, Mark Frost; Warren was also the father of the actress Lindsay Frost and the writer Scott Frost. One of the more distinguished alums of the Twin Cities.

January 29, 2022

This week in TV Guide: February 3, 1968

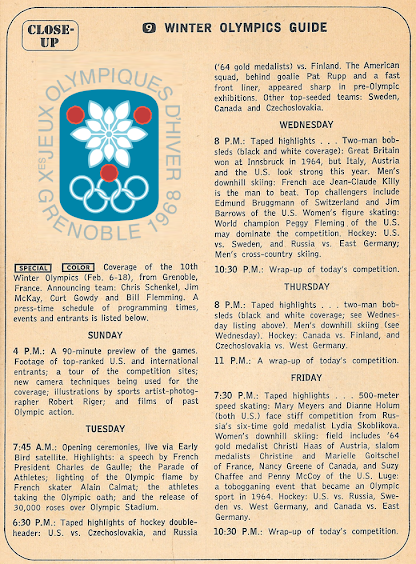

This week's big event is the opening of the 10th Winter Olympics from Grenoble, France*, and ABC is all over it. The network promises “a 27-hour Olympic orgy” with at least one prime-hour a night, a 15-minute nightly wrap-up, and daytime weekend coverage. Included will be unprecedented live coverage, via Early Bird satellite, of the Opening Ceremonies at 7:45 a.m. CT on Tuesday morning.

*Back in the days when the Winter Olympics were actually held, you know, in a country that has an actual winter climate.

The U.S. is hoping to make a better showing in this Games than in 1964, when speed-skater Terry McDermott was the lone American gold medalist (with the U.S. taking home a paltry six medals in total), but the only Yank with a real chance for the gold is America's sweetheart, figure skater Peggy Fleming. Nonetheless, ABC plans to cover all the angles, with a 250-man staff using 40 color cameras to bring the pictures back home. Roone Arledge wants the games to be more than just a technical marvel, though: "Figuring out where the drama will be and shooting it – that’s more important than technical wizardry." In other words, the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat – or, as Jim McKay would say many times over the years, "up close and personal”' – that’s the ABC way.

The U.S. is hoping to make a better showing in this Games than in 1964, when speed-skater Terry McDermott was the lone American gold medalist (with the U.S. taking home a paltry six medals in total), but the only Yank with a real chance for the gold is America's sweetheart, figure skater Peggy Fleming. Nonetheless, ABC plans to cover all the angles, with a 250-man staff using 40 color cameras to bring the pictures back home. Roone Arledge wants the games to be more than just a technical marvel, though: "Figuring out where the drama will be and shooting it – that’s more important than technical wizardry." In other words, the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat – or, as Jim McKay would say many times over the years, "up close and personal”' – that’s the ABC way.

Twenty-seven hours doesn't seem much of a broadcast “orgy,” does it? By the time of the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles, the TV schedule had expanded dramatically, to take advantage of the favorable time-zone (and to help pay for the enormous amount ABC was shelling out to win the rights). This kind of saturation coverage has remained the rule since, to the point that new sports are added, it would seem, simply to give the broadcasters more to show. Now, when you add up all the different platforms used to broadcast the Olympics, you've got more than 27 hours of coverage a day.

And so, when one looks at the Close-Up that accompanied ABC’s coverage of the first week of the Games, it’s kind of nice to see how simple things are, how naïve. The 1968 Winter Olympics were not free from controversy, but they were still a sporting event to be covered, not a made-for-TV spectacle that saturates everything in sight. What a concept.

l l l

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup.

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup.Palace: Host Phil Silvers introduces singers Connie Stevens, Jack Jones and Polly Bergen; comedian Henny Youngman; the Waraku Trio, Japanese pantomimists; and the rocking James Brown Revue.

Sullivan: Scheduled guests: singer-actress Michele Lee; comedians Jackie Vernon, Stiller and Meara, Morecambe and Wise, and Stu Gilliam; dancer Peter Gennaro; and acrobats Gill and Freddie Lavedo.

I think it's a pretty straightforward week; Phil Silvers is very funny, Henny Youngman can be very funny, Jack Jones is very smooth, and James Brown is very, very rocking. Ed's show isn't bad, mind you, but compared to the hardest-working show on TV the choice is obvious: the Palace dances all the way to the win.

l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era. This week we're on the mean, crumbling streets of New York, along with the cops of ABC's half-hour drama, N.Y.P.D.—or, as Cleveland Amory calls it, OKTV. Don't take that as an insult, though; "It may not be everybody's cop-in, but at least it's not a cop-out." For one thing, as the only network show filmed in New York ("Gun City"), it presents a look decidedly different from California. The small, 16-mm cameras make the entire city a shooting stage, taking us places we wouldn't normally visit, and it looks authentic.

There's also a well-written and well-developed trio of characters, with a good cast of actors playing them: Jack Warden as Det. Lt. Mike Haynes, who in Warden's hands is "believably tough and has believable heart"; Frank Converse as Det. Johnny Corson ("completely recovered, you'll be happy to know, from his trying amnesia in Coronet Blue"); and Robert Hooks as Det. Jeff Ward ("in TV, at least once in a while, handsome is as handsome does.") And the plots are good if sometimes a bit worn (one episode was a little psychopathic for Amory, but "it was nonetheless engrossing" with a fine performance from Hooks), and even when we have a bit too many clichés, the stories are "generally fine."

I reviewed this series myself a couple of years ago, so I was glad to see Cleve give it the thumbs up, but he does have one reservation: "in one episode there was a girl named Jilly Ammory. And they made her an ex-convict. Now why, we ask you, did they do a thing like that? Next they'll have some character who is an ex-critic."

l l l

The question isn't as rude as it sounds, nor is it as existential as all that. No, it refers to Paul Bryan, the character Gazzara plays in the hit NBC series Run for Your Life, who at the outset was given no more than eighteen months to live. The series is now in its third season; hence the question that dogs Gazzara throughout this press junket through New York, followed by TV Guide's intrepid reporter Edith Efron. At first Gazzara takes it in good humor, all bonhomme and masculine laughter, reminding an interviewer that "Little Orphan Annie never grows up," lauding the writers for keeping the series' quality high, the usual dog-and-pony act. But as the day wears on, Efron watches Gazzara's defenses start to drop. A one-minute plug on Hugh Downs' Concentration is followed by a radio interview with Ed Joyce, then an appearance on NBC with Lee Leonard, a talk with Art Fleming on NBC Radio's Monitor, an interview with Bob Stewart, a pre-Tonight show prep with Johnny Carson's staffers. And, bit by bit, the weariness and frustration that Gazzara feels toward series television begins to show.

To Joyce, who quotes the well-known director Elia Kazan as calling Gazzara "one of the three most brilliant actors working in the English language," he comes close to dropping the façade, baring the soul. "This kind of work doesn't tap all the muscles," he admits, and when Joyce suggests that some might view Gazzara as a sell-out, the actor doesn't argue. "The plays don't keep coming, the films are fewer and farther between. An actor has to work." This will be his last series, he promises, but "I'm coming out of this one with loot."

As the day progresses the bonhomme dries up, the answers become rote and mechanical, the eyes deaden. By the time of the interview with Bob Stewart, all his defenses are broken. Asked to complete the sentence "Doing a regular series is like ______," Gazzara replies, "Being in purgatory." Between interviews, he tells Efron that the problem is "that there's so little opportunity for complex acting" in Run for Your Life. "It's scripts, it's directors. I'm becoming interested in movies. Something is happening in European films. They're nonobjective, but they're personal. They're not the creation of a bunch of bureaucracies." Unlike television, he might as well have said.

The process of selling yourself is often a distasteful one for celebrities. It's the very thing that Sammy Davis Jr. found so difficult to stomach when his variety show started, and his failure to do it at the beginning, when it most mattered, was one of the many reasons for its downfall. Gazzara understands the necessity of turning himself into a "zoological creature" putting himself on display for tourists. But understanding it doesn't make it easier. When he sits down with Efron for the last time, after the Carson pre-interview, she says about the drained Gazzara that "It would be an act of cruelty to conduct an interview." All she can ask him, with a wry sympathy, is, "When are you going to die?" to which he says, with an exhausted smile, "You know, Little Orphan Annie . . . she never grows up," after which he finishes the last of his drink with a gulp.

This will be Run for Your Life's final season, and at the end Paul Bryan's fate is still uncertain; Gazzara will later say that viewers became cynical about the show's seeming disregard for Bryan's life expectancy. (One website, after a studied analysis of the timeline indicated by the episodes, estimated that the show covered about 20 months from first episode to last.) One can understand Gazzara's frustration with the series; I mean, if you were considered "one of the three most brilliant actors working in the English language," would you be happy while your peers were on stage and in the movies and you were doing a weekly show?

Maybe, for that sack full of loot.

l l l

Care for a quick look through the week?

On Saturday, Wide World of Sports (4:00 p.m., ABC) covers a semifinal bout in the heavyweight elimination tournament to choose a successor to Muhammad Ali, who was stripped of the title for refusing military induction. The winner of the Jerry Quarry—Thad Spencer fight will take on Jimmy Ellis later in the year for the heavyweight championship. Quarry will win the fight, Ellis will later take the title, and he in turn will lose to Joe Frazier down the line. But all that is another story.

Sunday afternoon features another of Leonard Bernstein's "Young People's Concerts" (2:30 p.m., CBS), this time an all-Beethoven program. Later in the afternoon, NBC carries final round coverage of the Bob Hope Desert Classic from Palm Springs, California (3:30 p.m.), which will be won by the great Arnold Palmer. And moving to primetime, the men of the Seaview confront the Abominable Snowman on Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (6:00 p.m., ABC). I wonder who will win?

On Monday, singer/actor/activist Harry Belafonte starts a one-week stint as guest host on the Tonight Show (10:30 p.m., NBC), with a star-studded lineup featuring Senator Robert Kennedy and his wife Ethel; Bill Cosby; Lena Horne; and actress Melina Mercouri and her husband, movie producer Jules Dassinn. A great lineup but wait until we get until Thursday. If you can't stay up that late, "One or My Baby," an episode of Danny Thomas's anthology series, has a few stars of its own in Janet Leigh and Ricardo Montalban (8:00 p.m., NBC).

In addition to the opening of the Olympics on Tuesday morning, Mike Douglas welcomes former Vice President and current presidential candidate Richard M. Nixon (4:00 p.m., WCCO). I Dream of Jeannie (6:30 p.m., NBC) gives us a thorny problem: Jeannie's locked in a safe, which has an explosive mechanism that will go off unless a demolitions expert can disarm it. Making things more difficult, the man who opens the safe will become Jeannie's new master. How does it end? Tune in next week and see if Larry Hagman's still in the credits. For less suspense, Tuesday Night at the Movies (8:00 p.m., NBC) has McHale's Navy Joins the Air Force; that's the one without Ernest Borgnine. Where is he? Guest starring on The Jerry Lewis Show (7:00 p.m., NBC), of course!

You remember that on Tuesday I mentioned Thursday night's Tonight Show lineup? Harry Belafonte's guests are Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Paul Newman and comedian Nipsey Russell. And herein lies a difference between late-night talk shows of the past and present. Belafonte had an incredible guest lineup that week; I haven't even mentioned Sidney Poitier, Robert Goulet, Aretha Franklin or Dionne Warwick. One of Belafonte's guests is a Nobel Prize winner, the other is a candidate for president of the Unite States. Can you imagine Kimmel or Fallon with that kind of a lineup? Or that two of the biggest headliners would be dead less than five months later? (I wrote about Belafonte's week as host here.)

NET has another of its unusual dramas at 10:00 p.m. on Friday. Entitled "The Successor," the British play "focuses on the deliberations of a convention [in other words, conclave] of Catholic cardinals as they elect a new pope. The cast contains characters such as the Cardinals of Palermo, Boston and Paris, plus some generically named prelates. I wish I could find something more about it, but I can't. This is the year Pope Paul VI releases his encyclical Humanae Vitae, after which many in the media probably wished the Church was meeting to select a new pope.

l l l

Finally, this week's TV Teletype gives us a preview of coming attractions. Sheldon Leonard, the producer of I Spy, has acquired rights to James Thurber's works with the intent of making an hour-long series for the 1968-69 season. That turns out to be My World and Welcome to It, which stars William Windom. It premieres on NBC in 1969 and runs only 30 minutes, but though it's cancelled after a single season it's still fondly remembered by many classic TV fans.

ABC has plans for a new daytime chat-and-info show called This Morning, a 90-minute daily show that premieres next month. It's hosted by Dick Cavett, and will run in daytime for less than a year before shifting to prime time, and then to the late-night slot to replace Joey Bishop.

And then there's the one that got away, the one we would have liked to see. It's a pilot called City Beneath the Sea, and if all goes well for producer Irwin Allen, it will become part of the primetime schedule. "It's about a futuristic city under the ocean," writes Joseph Finnigan, who adds that "Maybe [Allen'll] cast Lloyd Bridges as mayor." Sadly, the movie never turns into a regular series, and we're forced to conclude that Finnigan is right. Imagine Lloyd Bridges as mayor, with Richard Basehart and David Hedison as head of the city's defense system? It's a sure-fire idea, that is. TV

January 28, 2022

Around the dial

What with the raft of deaths we've had in the last couple of months, it's kind of nice to celebrate the career of someone who's still alive, don't you think? That's where we'll start this week, with David's retrospective at Comfort TV on the top TV moments of the lovely and talented Teri Garr.

It's a pretty good chance that an episode with the title "You'll Be the Death of Me" has a double meaning, and comes to no good. Head over to Jack's latest Hitchcock Project at bare-bones e-zine and see if that's the case with William D. Gordon's ninth-season story, starring the great Robet Loggia.

At Cult TV Blog, John looks at the first television effort of the British radio comedian Tony Hancock, his eponymously named 1956 sketch comedy show, with the show's fourth episode. I'm always interested by these British shows, even (or especially?) the ones where both the show and the star are a mystery to me. I have to take the time to further my collection; maybe after I'm retired?

RealWeegieMidget's Odd-or-Even Blogathon has wrapped up; I wish I'd had time to take a crack at this one, but Gill promises there'll be more opportunities coming up, and hopefully I'll be in a better position to be part of them. And speaking of which, at A Shroud of Thoughts, here's Terence's entry: the 1967 heist film The Jokers, starring Michael Crawford and Oliver Reed, which sounds like a winner.

From Television Obscurities, something to think about if you're available on February 10: the UCLA Film and Television Archives will be streaming "The Sty of the Blind Pig," a play presented as part of the PBS series Hollywood Television Theatre in 1974, directed by Ivan Dixon and starring Mary Alice, Maidie Norman, Richard Ward, and Scatman Crothers.

One of the news stories that I remember vividly from my childhood was August 1, 1966, when Charles Whitman took a rifle to the observation deck of the tower at the University of Texas in Austin and used it to murder 16 people. (I particularly remember the eerie scenes of television cameras trembling slightly as they focused on the tower while Whitman was shooting.) At Drunk TV, Paul recalls the event while reviewing the 1975 telefilm The Deadly Tower, starring Kurt Russell as Whitman.

Finally, ending on an upbeat note, at The Lucky Strike Papers Andrew has been sharing some pictures of his mother and father; he wrote about his mother, singer Sue Bennett, in the delightful The Lucky Strike Papers: Journeys Through My Mother's Television Past, which I reviewed here. TV

January 26, 2022

Sic transit gloria television

|

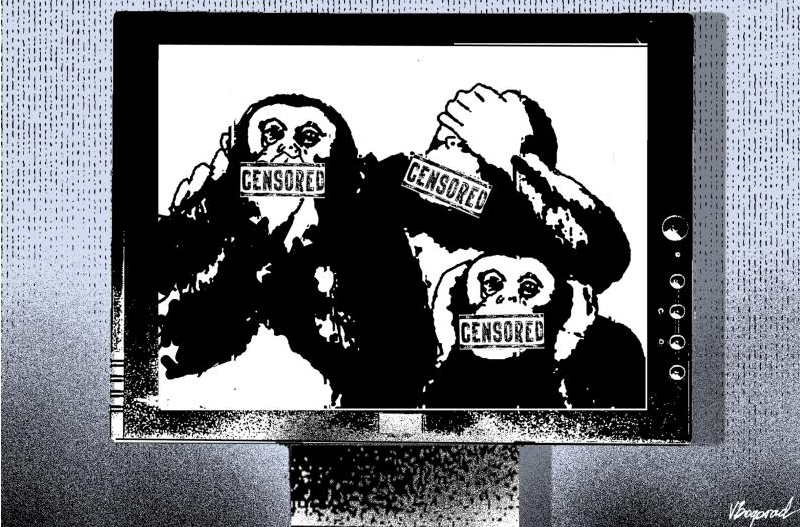

| Victor Bogorad |

I’ve been thinking a good deal about television lately, which perhaps isn't surprising to you given that I write about it here four days a week. For the last couple of weeks, I've focused on how television entertains, and why it must entertain. This week, I want to speculate on the effect that contemporary culture might have on classic television.

In talking about "classic" television, one of the questions we frequently face is: how do we define "classic"? Is it a show from before you were born? One that aired when you were a teenager? Does it have to be in black-and-white or not? There is no "right" answer, because the word—and the shows themselves—have an intensely personal meaning for each person. As I've said before, television is the most personal of media, and our relationship with the shows we watch bears that out.

But here's a question I don't think I've considered before, or at least not in the way that I'm going to pose it now, which is:

Are we ever going to be able to enjoy an old television series again?

The springboard to this discussion is an article by Carl Trueman at First Things entitled, "The Strange Fate of Hamilton and Harry Potter." (Now, there's a pairing you don't see very often.) The point of Trueman's perceptive article is, as he says in the lead paragraph, "moral relevance in the modern world [is] a cruel and fickle mistress." In other words, what works today doesn't necessarily work tomorrow.

You're probably familiar with some of these situations, programs such as Amos 'n' Andy that are no longer aired because the premise is supposedly objectionable, or out of touch with modern sensibilities.* In the case of Amos 'n' Andy, the show was still being aired in syndication in Minneapolis as recently as the early 1960s; CBS pulled it from syndication in 1966, and according to the always-reliable Wikipedia, it hasn't been broadcast regularly nationwide since, except for a run from 2012-2018 on the now-defunct Rejoice TV network. Like another banned classic, Disney's Song of the South, you can find Amos 'n' Andy if you look hard enough.

Trueman doesn't have to go back as far as Amos 'n' Andy, and that's part of the point he's making. Indeed, the examples are hardly ancient history:

Last week, Constance Grady at Vox noted how so much pop culture of recent vintage has dated so rapidly. Hamilton, the hit musical of 2015, now appears, in 2021, to glorify “the slave-owning and genocidal Founding Fathers while erasing the lives and legacies of the people of color who were actually alive in the Revolutionary era.” The TV series Parks and Recreation is now considered “an overrated and tunnel-visioned portrait of the failures of Obama-era liberalism.” And the Harry Potter franchise is now “the neo-liberal fantasy of a transphobe.”

The moral tastes of culture, Trueman notes, have always changed over time. "What is notable today," he points out, "is the speed at which they change and the dramatic way they repudiate the past." He cites the backlash to John Cleese's 40-year-old Hitler impersonations as an example of how things used to be, before a combination of social media and changing tastes condensed the timeline rapidly. "But now, jokes that were unexceptional five or ten years ago might well cost a comedian his career today. The moral shelf life of pop cultural artifacts seems much shorter now and the criteria by which they might be judged far less predictable." It must be exhausting to have to constantly monitor the offensiveness of such things.

Such examples of what people refer to as the cancel culture aren't limited to individual programs or movies, of course—the Harry Potter stories find themselves victims not so much due to what they contain, but because of the personal views of J.K. Rowling. Numerous stars have found themselves ousted from television shows or movies because of their vaccination status; setting aside the legality of such acts, there's no question that you're more likely to find favor with the dominant arbiters of social acceptability if you've received the jab (although this, pray God, may be changing). It's true that this is hardly new in the entertainment world; try finding Bill Cosby or Robert Blake on television, or Kevin Hart hosting the Academy Awards. What is different, though, is the speed with which such blacklisting is taking place—in this case, happening virtually in real time.

Trueman identifies the real problem as that "the moral tastes of popular culture are just that: tastes, and thus subject to fashion and, in our social media age, to easy manipulation. Society has no solid foundation on which to build its moral codes." While most people don't give this much thought—and would probably laugh derisively at those who do—Trueman says the inevitable result is a world, "with no agreed upon moral compass and marked by a deep suspicion of any attempt by any one group to make its truth normative, out of fear that the result will be oppressive and unjust.

With that as the backdrop, let's return to my initial assertion that we might have a hard time being able to enjoy old TV shows. Yes, it's pretty easy to find Parks and Recreation on streaming services or in DVD, but imagine that the show's crime against society was more egregious, picking on a group or issue destined by some future ruling class to be protected. "Today race theory, not feminism, might be the critical theorists' soup du jour," Trueman writes, "but this will prove no more lasting than previous iterations of the voice of the oppressed. Intersectionality witnesses to that fact; and those who live by the sword of critical theory can expect at some point to die by the same." Under such constant flux, "today’s virtuous icons are tomorrow’s vile scoundrels."

Under these circumstances, will you be allowed to enjoy old television shows, or will they have to undergo some kind of cultural CAT scan to determine whether or not they're suitable for a general audience? Look no further than YouTube for examples of content being censored; I recall awhile back that the app was banning documentaries about Hitler because he was such an offensive guy—notwithstanding that the content of many of these programs was devoted to demonstrating how Hitler was such an offensive guy. The powers-that-be were still worried that some Hitler cult could use the footage to drum up support for der Fuhrer.

Anyone can be offended by anything, of course; I'm sure there's someone out there who finds the early seasons of My Three Sons offensive because it proves that boys can be raised in a healthy environment without the presence of a woman. But—and here's where this ties in to my previous two essays—if television shows persist in being controversial, in being political, in advocating particular social stands, then they run an increasing risk of saying the wrong words, portraying the wrong deeds, winding up on the wrong side of this week's history. Post hoc, of course.

We've complained for a long time that network executives keep new shows on too short a leash, refusing to give them enough time to grow and cultivate a following. What we're experiencing here is the cultural equivalent, a kaleidoscope of opinions and mores that makes the fluttering of a hummingbird's wings appear in slow motion by comparison. For, as Trueman concludes, "Today, moral tastes have too short a shelf life for that. Indeed, embracing the moral spirit of the age is now more akin to having a one-night stand—and that with somebody who kicks you out of bed in the morning and calls the police." And you can probably watch it on TV that night. TV

January 24, 2022

What's on TV? Wednesday, January 27, 1954

These early 1950s Chicago TV Guides have an interesting way of describing programs—short and to the point, and kind of colorful. Take this description of Irv Kupcinet's show: "Gossip and interviews." Well, yes. Herbie Mintz: "Melodies, old and new." OK, it you say so. Some of them are kind of banal, but no less truthful, such as Winston Burdett's news program: "A look at the headlines." Can't deny that. On Kids' Karnival: "Clowns entertain the kids." (Funny; I thought that was C-SPAN.) Stuart Brent's show: "Advice and information for women." And Dorsey Connors' pre-late news show (labelled "Ideas"): "Reading in bed." Things really were simpler back then, weren't they?

January 22, 2022

This week in TV Guide: January 22, 1954

Back in the day—and that is, after all, what this site is all about—there were a number of television centers in addition to New York. There was Los Angeles, which would soon enough surpass New York; Philadelphia, where Ernie Kovacs and Edie Adams came from, and Chicago. And since this is the Chicago edition of TV Guide, you can probably guess which one we're discussing this week.

One of the many drawbacks to the corporate takeover of media is that the ability to work your way up from the sticks to the big city just isn't what it used to be. With the exception of local news, there aren't really many changes for somebody to make it big with a local talk or variety show, or as a radio DJ. (I'm not even sure many DJs exist anymore; ask iHeart.) Anyway, the point is that the Chicago School of Television, as it was known, produced a pretty fair number of celebrities and shows you might have heard of, all with a style that was distinctive, "relaxed, intimate, friendly, natural, subtle," according to Look magazine, but always one in which "[T]he viewer doesn't always know what's going to happen next and next and next." Dave Garroway; Studs Terkel; The Bozo Show; Zoo Parade, with Marlin Perkins; Hawkins Falls, one of television's first soap operas; Ding Dong School; Burr Tillstrom's Kukla, Fran and Ollie; Mike Douglas, who first made an impact on WGN's Hi Ladies. Quite a track record, wouldn't you say?

"Chicago Dateline," the local section of this week's issue, gives us an update on shows that continue the tradition: Mr. Wizard, for instance, with Don Herbert, who still promotes Chicago as a "quality TV stronghold." It's currently seen in 71 cities each week, and Herbert "expects to have 20 more markets on his list by the time he celebrates his third anniversary early this March." In the meantime, Ben Parks, producer of the aforementioned Hawkins Falls, is pushing for NBC to move the soap Three Steps to Heaven from New York (where it's the last Gotham-based soap on the network) to Chicago. The reason: cheaper production costs in Chicago. Who knew that it was a 1950s version of Canada? Don McNeil's Breakfast Club, a Chicago institution, is about to return to ABC, and the originating station, WBKB, plans a "wake-up" music show at 7:00 or 7:30 a.m. And DuMont's Music Show, which originates in Chicago (even though it isn't seen here) may return on the network's local affiliate, WGN.

Network television is often accused of being stagnant, repetitive, boring. I wonder if it would have continued that way if multiple cities had maintained their own TV hubs, developing their own schools of broadcasting.

Oscar winner Ray Milland starred for two seasons in the sitcom Meet Mr. McNutley, another show with its roots on radio. In this case, however, the radio and television versions aired concurrently during the show's first season (Milland starred in both); unusual, perhaps, but not unheard-of, as Dragnet did separate stories on radio and television the first few seasons. I'm sure there are many other examples. At any rate, in Thursday's episode (7:00 p.m., CBS), Ray and his friend Pete (Gordon Jones) are finally letting Ray's wife Peggy (Phyllis Avery) accompany them on their camping trip—as long as she disguises herself as a young boy. Not sure if this should be taken as sexism or science fiction.

l l l

Anyone in entertainment knows the value of a good warm up act. "As a precaution" against cold, unresponsive audiences, the warm up act is there to make sure that, come airtime, "the audience will be giddy enough to laugh at anything."

Bob Hope has long been his own warm up; "Approximately a minute before airtime, he reads from the script what is allegedly the first joke on the show. He then ceremoniously rips the first page off, crumples it in a ball, throws it on the floor, and kicks it." Hope times things so that the audience is still roaring at the very moment the show starts. The singer Jane Froman plays a part in her warm up as well; while her announcer is chatting with the audience, Jane can be heard singing that night's songs in her dressing room, located very near the stage. And Ed Sullivan reminds his audience members to laugh when the cameras are facing them; "You don't want to disgrace your grandpa back home in the corner saloon. If he sees that you're not smiling, he'll think you're not having a good time."

One of the challenges faced by a warm up act is to make sure he's not funnier than the main event, so Your Show of Shows' Ed Herlihy (you know him for narrating the Kraft recipe commercials of the day), as is the case with other comedy shows, treads the line carefully, reminding the audience to relax, have a good time, even take their shoes off if they feel like it.

And one of the most unique warm ups comes on Bishop Fulton Sheen's Life is Worth Living. One of the show's two announcers, Fred Scott or Bill O'Toole, tells the audience to enjoy themselves, laugh and applaud when they feel like it, and "remember, above all, that it is not in church."

l l l

Is it possible for me to talk about the Hallmark Hall of Fame without going into a tirade about the current version? Why, yes—just watch me! On Sunday (3:00 p.m. CT, NBC), Hall of Fame presents a high-class (and probably live) adaptation of Shakespeare's Richard II, with Maurice Evans as the King, Kent Smith as the conniving Bolingbroke, Sarah Churchill as the Queen, and a pre-Untouchables Bruce Gordon as Mowbray. Hall of Fame is preceded at 2:30 p.m. by a whimsical episode of Kukla, Fran and Ollie involving the Kuklapolitans doing a Shakespearian play ("to set the mood" for Richard II); their problem is that they can't decide which play to adapt!* And on Omnibus (4:00 p.m., CBS), one of the segments features Lew Ayres, starring in a performance excerpted from the French film The Spice of Life.

*Now, that wasn't snarky at all, was it?

As you know, many of television's early stars came from radio, and in turn from vaudeville, and it's interesting to see that reflected in Monday night's episode of Burns & Allen (7:00 p.m., CBS), in which, as part of a typical episode, George and Gracie do "Lamb Chops," the routine that first made them famous. "This act was placed by Joe Laurie, Jr. on his ideal vaudeville bill consisting of the greatest acts in vaudeville history." I think that deserves a look, don't you?

Helen Hayes is billed as "America's Most Distinguished Actress" in the ad for Tuesday's Motorola TV Hour presentation of "Side by Side" (8:30 p.m., ABC), so with a build-up like that, I guess we'd better look at it. It's the story of a successful housewife and mother who's so prominent in civic organizations that she's urged by prominent politicians to run for Congress. A setup like this is ripe for a dramatic story, considering that the 83rd Congress, which sat from 1953-55, had a grand total of 13 women in Congress (five Democrats and eight Republicans, in case you were curious). I wonder how it turns out?

Helen Hayes is billed as "America's Most Distinguished Actress" in the ad for Tuesday's Motorola TV Hour presentation of "Side by Side" (8:30 p.m., ABC), so with a build-up like that, I guess we'd better look at it. It's the story of a successful housewife and mother who's so prominent in civic organizations that she's urged by prominent politicians to run for Congress. A setup like this is ripe for a dramatic story, considering that the 83rd Congress, which sat from 1953-55, had a grand total of 13 women in Congress (five Democrats and eight Republicans, in case you were curious). I wonder how it turns out?

Boxing is still the big sport on television, but of the four televised fights this week, there's only one that's really worthy of attention: Wednesday's world light heavyweight title fight between champion Archie Moore and challenger Joey Maxim, live from Miami Beach. (9:00 p.m., CBS) Moore, one of boxing's all-time greats, held the light heavyweight championship longer than any man, for ten years. (Needless to say, Moore wins this fight, in a 15-round decision.) After his career ends in 1963 (one of his last fights is a loss against young Cassius Clay), he becomes a successful character actor in television and the movies and is prominent in civil rights and youth causes. Quite a legend, he was.

|

| Sure, I'd believe she's a boy. |

Friday's highlight, as it often is, is probably Edward R. Murrow's Person to Person (9:30 p.m., CBS), with tonight's special guest Eleanor Roosevelt, speaking from her New York apartment. Setting aside political allegiances, has there been any former First Lady who remained as much a part of politics and the world as she did? Jackie Kennedy was always a tabloid sensation, but as far as I know she was never much of a mover in the Democratic Party as Mrs. Roosevelt. She really did carve out quite a life for herself apart from FDR.

On Saturday, Jackie Gleason devotes the entire hour to a Honeymooners sketch in which Ralph and Alice decide to buy a summer cottage. (7:00 p.m., CBS) I wonder how Norton fits into the scene? Later this evening, on The Martha Raye Show (8:00 p.m., NBC; the monthly show that fills in for Your Show of Shows), Martha's got a great guest lineup, with Edward G. Robinson, Cesar Romero, and former boxer Rocky Graziano.

l l l

I mentioned in that last paragraph that Martha Raye replaces Your Show of Shows once a month; well, as it so happens, Your Show of Shows is the show that Dan Jenkins reviews as the "Program of the Week." And it's probably a dead giveaway as to what he thinks of it when he refers to it, in the first sentence, as "The Eighth Wonder of the World, Show Business Division." The revue, starring Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca, Carl Reiner, and Howard Morris, has come to be considered one of the legendary shows of the Golden Age, and the three-times-a-month, 90-minute show should, Jenkins says, "have collapsed of its own weight years ago, but is apparently as durable as Old Man River himself."

That's not to say that the show is perfect, though; after all this time, it "lacks today the freshness it once had in such great abundance," as well as showing "a tendency to repeat sketches and numbers." It takes more than one great sketch a week to make the viewers feel that the entire show was great, "and it is not every week these days that they are coming up with even one standout." Even with that, Your Show of Shows remains worth the effort to catch, and Caesar and Coca often fly into "sheer comic greatness." Although the material may be harder to come by these days, "there is no one in their field who can touch them."

The idea that the show is starting to feel its age isn't an illusion on Jenkins's part. The ratings start to slip this season, and NBC will make the decision to split up Caesar and Coca and give each of them their own series. The last episode airs on June 5. Although I think Caesar has more solo success than Coca, neither of them, separate or together, ever reach the heights of Your Show of Shows. But what heights they were.

l l l

Another show Jenkins reviews is The Les Paul and Mary Ford show. It's a brief review, which is appropriate because the show only runs for five minutes. Yes, five minutes—and you thought those 15-minute music programs that take up the other half of the evening news slot were short!

Les Paul, of course, is a genuine legend, "a jazz, country, and blues guitarist, songwriter, luthier, and inventor," as his Wikipedia page describes him, "one of the pioneers of the solid-body electric guitar, and his prototype, called the Log, served as inspiration for the Gibson Les Paul." And what did you do today? Paul is the only person in both the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the National Inventors Hall of Fame, two areas that I imagine have a pretty small overlap. His wife Mary (real name: Colleen Summers; the couple were introduced by Gene Autry) served as the vocalist, to great success.

So the show: as Jenkins describes it, "it's over almost as soon as it starts. Paul and his wife get off two quick songs, the sponsor is in for two quick messages and that's it." It's economical, I'll say that; there are other shows out there that would take 15 minutes to get all that in. It has "an easy casualness that belies the careful production" of the show, and Paul's guitar virtuosity, combined with Ford's "full-throated quietness," complement each other perfectly.

The show airs on NBC for a single season, filling in where needed on the schedule, and then goes into syndication until 1960. And that's the real problem, according to Jenkins, since the show has no set schedule: "It's like trying to find a lone daisy in a rose garden." Heck, it isn't that hard—you can see it right here:

l l l

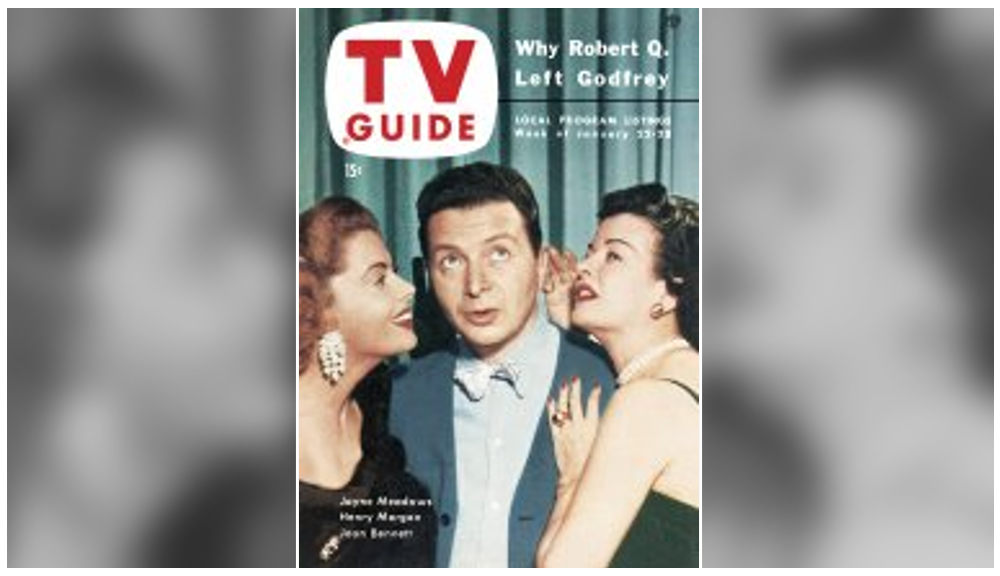

Here's a news bulletin for you: man leaves Arthur Godfrey show on good terms! It's Robert Q. Lewis, the permanent substitute host for Godfrey, who departed the Old Redhead, with his blessings, for his own five-day-a-week CBS show. Lewis, unlike many who've left the Godfrey camp, has good words for his mentor; "I'm very grateful to him for allowing me to grow at the same time he was growing. Anytime he ever wants me for anything, I'll be glad to cooperate."

Godfrey may have allowed Lewis to "grow," but that doesn't mean he didn't water the seeds, as it were. During Godfrey's hip operation last year, he would direct the show from his hospital bed, phoning the control room as he watched the show on TV. Lewis remembers one time when he was struggling for a laugh from the studio audience; the producer passed Lewis a note from a Godfrey phone call. "Bob's trying too hard," it read. "Tell him not to worry."

Arthur Godfrey wasn't the start of Robert Q. Lewis's career; he'd been drawn to acting when he was a boy, suffering with asthma that prevented him from more physical activities. He studied dramatics through college at Michigan, and then dropped out to work out at a radio station in Troy, NY. "He knew he would be drafted soon, and wanted to get a start in the business, to have something to return to after the war." He would then circulate through a series of radio gigs until his first television opportunity with Godfrey. Since then, he's worked in summer stock and nightclubs.

In addition to hosting his own variety show, Lewis is helming the game show The Name's the Same, and it will be for his participation in game shows, as both host and panelist, that he will be most remembered. He was a Goodson-Todman favorite, appearing more than three dozen times as a panelist on What's My Line?, as well as To Tell the Truth and both versions of The Match Game (and how many people other than Gene Rayburn can say that?) TV

January 21, 2022

Around the dial

Oh, why don't we start this week at The Horn Section, as Hal returns to the world of Love That Bob and the episode "The Double Date," in which Bob finds himself stuck having to take nephew Chuck (the late Dwayne Hickman) out for his 18th birthday the same night Bob has a date with the delectable Boom Boom Laverne.

At Cult TV Blog, it's "Detectives on the Edge of a Nervous Breakdown," a very, very funny parody of four of the most popular British TV detectives of the 1970s, as seen by the stars of the London comedy club "The Comic Strip."

Cary O'Dell has a wonderful article at TV Party (courtesy of the Broadcasting Archives) on a Christmas gift boxed-set of the complete Lucy Show, which demonstrates that Lucille Ball's career after I Love Lucy was far from, as one critic put it, coasting on the “fumes” of her past glories.

The tributes to Betty White continue to pour in, and this week it's The Last Drive In, where Joey gives us a clip-filled retrospective of Betty's career. And it was quite a career, wasn't it? And that's not all—

Meanwhile, over at A Shroud of Thoughts, Terence looks at her groundbreaking first sitcom Life with Elizabeth, of which Betty was a co-producer, one of the first women to fill such a role. (Terence also has a great piece on the 50th anniversary of Sanford and Son that you should check out.

At RealWeegieMidget, it's the start of a new blogathon: the Odd or Even Blogathon. Rather than have me try to explain it, why don't I just send you over to Gill's site so you can see for yourself. And Gill, don't hold it against me that I haven't been in the last few. I'll be back again, I promise!

Finally, Terry Teachout—author, drama critic at The Wall Street Journal, opera librettist, essayist and playwright—died last week at the far-too-young age of 65. You might recognize the name; I mentioned him many times here, and a couple of times in The Electronic Mirror. I never met him, but we corresponded several times through Twitter. He had some very kind things to say about my writing—both the blog and the book, which he had read and enjoyed. He wasn't singling me out for praise; Terry was a generous man, always quick to let people know when they'd said or written something that gave him pleasure, a lesson we could all learn. Whenever I asked him a question, he was quick to try and find an answer, even if it meant tweeting his friends in search of it. His books, like his writing, were elegant and straightforward, a pleasure to read. It's always seemed to me that social media has played fast and loose with the term "friend," but if it's possible to have as a friend someone you haven't met, then he was a friend, and I will miss him. TV

January 19, 2022

Matter and antimatter, hero and antihero

As I believe I've mentioned before, I don't watch a lot of contemporary television. There are a few shows I make a point of checking out—well, one, at least—but aside from sports and the odd special, I mostly stick to my streaming and DVD favorites. I've wondered about this, more than once. Last week I offered one possible reason for it; today, I'm back with another.

There seems to be little doubt, based on what I've read anyway, that the family in the HBO series Succession is one of the most disagreeable, disgusting, dysfunctional, and loathsome families seen on television this side of Helter Skelter. It's also one of the most popular on prestige cable, at least when it comes to critical acclaim and social media conversation. And it isn't just me who thinks this; at The Ringer, Andrew Gruttadaro describes one member of the family thusly: "Josh is just like the rest of the far-too-wealthy assholes in this craven world, treating humans like toys and turning into a playground bully at the faintest sniff of power."

As you know, I like watching television—probably more than I should. But a steady diet of this? Seriously, why would anyone get any pleasure out of watching a bunch of clowns like these, especially when the only people who appear capable of taking them down are other clowns who are just as bad, just as selfish and greedy, just as opportunistic and exploitative? I mean, can you actually enjoy something like this?

What we witness in these programs is the rise of the antihero, the central character you love to hate.* If you were paying attention in your high school science class (or to any science fiction movie or series), you know that matter and antimatter particles are always produced as a pair, and if they come into contact, they annihilate one another, leaving behind pure energy. Now, producing pure energy is, or should be, the ultimate goal of the creative process; how many times have we approvingly noted that a show has such energy that it jumps off the screen? But just as matter requires antimatter to produce energy, I contend that an antihero requires a hero in order to produce the energy that is required for entertainment. Take The Fugitive, for example; its paring of Richard Kimble and Philip Gerard is essential to creating the dynamic, the energy, that keeps the show going. Try to imagine The Fugitive without Gerard; Kimble might still be on the run from the cop du jour, but it's nowhere near as enthralling a chase as it is with Gerard as an adversary. (Even though Gerard is only in less than a fourth of the episodes, he hovers over all the rest like the sword of Damocles.) And a diet consisting only of antiheroes, just like a diet exclusively of desserts, is eventually going to make you sick, no matter how appealing it might seem at first.

*Said to have started with Tony Soprano, the head of the crime family featured in The Sopranos.

When I think back to my own viewing habits, the closest proximity I can come up with to a show like Succession is the original House of Cards, the brilliant British black comedy (not the American version!*) on corrupt politics and politicians, and its two sequels. There, too, the focus of the story is an antihero—Francis Urquhart, the scheming MP who becomes prime minister utilizing a backstage campaign of blackmail and murder—and the unfortunates who oppose him, most of whom have their own feet embedded in clay. A neutral observer might despair at watching such a cesspool of unlikable characters.

*Which I haven't seen and wouldn't comment on.

There's a difference, though, I think. In the hands of the great Ian Richardson, Urquhart has a certain irresistible charm; his constant breaking of the fourth wall draws us in, makes us co-conspirators in his nefarious plots. We start out in each series rooting against him, but find ourselves drawn into his orbit, in spite of ourselves, hoping that he might get away with it one more time. We never lose sight of his misdeeds, which are grave indeed, but Richardson's performance makes Urquhart a human being, an insecure man despite all his outward confidence, a weak man who turns to evil in an effort to draw strength. One can look at him and see the kernel of a decent man down there, deep inside him, buried under layers and layers of corruption over years and years of working in a dirty, cynical business. It's no stretch to compare him to Willie Stark, the antihero of All the King's Men, to imagine Urquhart as a man who got into politics with (at least partially) noble ideas, only to have them slowly erased as he learns how the political game is played. And when Urquhart, at the end of the final chapter (The Final Cut) does, in fact, meet his comeuppance, it carries little of the satisfaction that we might have hoped for at the beginning.

I don't know if it's fair to compare House of Cards to Succession, partly because we don't know how the latter will end, and partly because of the difference between American and British television, which is profound. Perhaps somewhere within the Roy family, there is a character with a spark of human decency and ethics, someone who can draw the viewer in without making us feel as if we need a bath afterward. What we do know, however, is that the antihero has become a staple of storytelling today. Look at Tony Soprano and his cohorts in The Sopranos; look at Breaking Bad's Walter White, or Dexter's eponymous serial killer. We may sympathize with each of them at one time or another, but ultimately they cross a line that makes it impossible for us to follow them.

There's a point I've made many times before, an observation from the dramatist Dorothy L. Sayers, that the central theme of a murder mystery is the restoration of the world to truth through the equilibrium of justice; if justice is not dispensed, the equilibrium does not exist, and the mystery fails. We all know that life is the greatest drama of all, as well as the greatest mystery, and that the equilibrium of justice, in the form of the battle between good and evil—between matter and antimatter, hero and antihero—is one of the existential foundations of life.

What I'm getting at here is that one of the things classic television has going for it is that, many times, it is simply more enjoyable to watch than what one sees on screen today. In our age, "wholesome" has become a synonym for bland, unrealistic, old-fashioned; and this can be true, especially if the result puts the viewer into a diabetic coma, or when the purpose is to preach, to proselytize, to make storytelling secondary to speechifying. That's not to say that the story must be brainless, its themes witless; rather, it's that you're never going to get your point across if you're not good at telling a story. Those programs that make antiheroes the heart of their storytelling may well be great storytellers as well as talented artists, but the portraits they present are ugly, dark, dehumanizing ones. When we are fed a constant menu of antiheroes, missing the subtext of that struggle, or lacking the hope of redemption, should it be any surprise that we've become a culture of self-involved, narcissistic individuals, brooding and depressed, without much hope or much to strive for? Is it a coincidence that, to me at least, the rise of the antihero coincides with the fall of contemporary television?

And so we come back around to the beginning, and if the primary purpose of television is to entertain, then close behind it is the need to strike the sympathetic chord, to get the viewer to identify with what he or she sees on screen. I don't know about you, but I face enough darkness in real life, and when I turn on the television, when I stream the latest hit drama or comedy, I don't want to be surrounded by people I don't like, people I'm not meant to like. I don't want to identify with the Tony Sopranos, the Walter Whites, the Logan Roys of the world. It all reminds me of something the late Peter Bogdanovich once said to writer Peter Tonguette, speaking of directors like John Boorman, William Friedkin, and Martin Scorsese: "They all deal with stereotypes or gangster figures who are sort of stereotypical or aberrations of human behavior, like Raging Bull, but not real human beings. They’re sort of monsters." These characters may be realistic, but are they real?

Not every story has a happy ending (especially true ones), but often the unhappiness comes from falling short, from striving and failing to attain a higher end, whether it be romance, victory, or justice. The story doesn't necessarily have to be uplifting: but a little decency wouldn't hurt. TV

January 17, 2022

What's on TV? Thursday, January 21, 1965

We're in Boston this week, with some additional stations from surrounding areas. Of course, we have some interesting items. For example, Regis Philbin, pre-Joey Bishop, pre-Kathy Lee! Can you believe it? WBZ, the NBC affiliate in Boston, carries Rege's nationally syndicated talk show, based on his successful local show out of San Diego, that started the previous October and would last another month. As was the case with the format followed by Mike Douglas, Rege would have a co-host that would be with him for the entire week. Although no guests are listed in the TV Guide, a little Internet research suggests his co-host for the week might have been Eartha Kitt. Because WBZ is carrying the Philbin show, The Tonight Show is being carried at 9:30 p.m. on WHDH, a CBS affiliate. Someone more familiar with the area could probably tell me why WBZ didn't carry the Carson show.

And then there's the Harry S Truman program on WTIC in Hartford. This is, I believe, Decision, a series of 26 half-hour episodes that were syndicated during the 1964-65 serason. It was originally proposed by David Susskind, but after failing to secure enough interest with one of the broadcast networks, he gave the project over to Screen Gems, who eventually put the series together. As Stephen Battaglio points out in his Susskind biography, it was possible that "network executives knew Truman was still not very popular with the public and certainly not as compelling on the TV screen as the "Give 'em hell, Harry" mythology that was later built around him." Perhaps this series had something to do with it; American Cinema Editors later named Truman the outstanding television personality of 1964.

January 15, 2022

This week in TV Guide: January 16, 1965

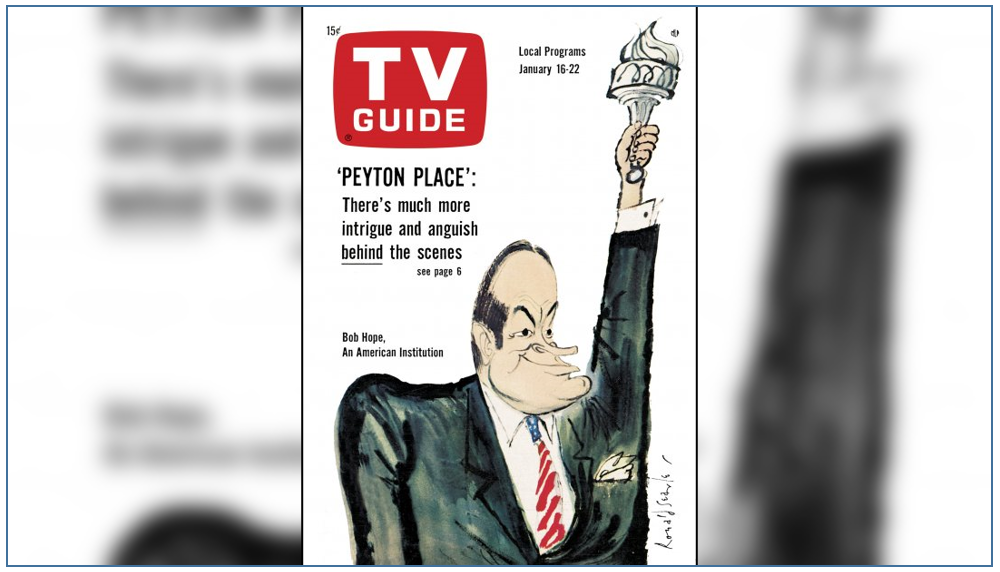

Well, I wanna tell ya, in 1965 there was no doubt that Bob Hope was, as the cover says, an American Institution, and had been for quite some time. It is not lightly that we dress someone in a red, white and blue tie and pose him as the Statue of Liberty, after all. And yet, to some—as the late Terry Teachout (and you don't know how much it pains me to say that) pointed out in this essay from a few years ago—Hope is, today, a forgotten man.*

*I wrote about that Teachout piece when it first came out, though I'm not of a mind to go back and look up what I wrote back then. What Teachout wrote was thoughtful and provocative, as he usually was, but as I've thought more about it, I've come more and more to disagree with it, as you'll soon see.

What makes a man an institution? As Dwight Whitney writes, it's more than whether or not you're funny. Hope "has long ceased to be a mere jokesmith, quipster, and all-around funny fellow." He is a man who has traveled to virtually every country in the world, often at Christmastime. He is a man called upon by the State Department to use his prestige in the cause of international diplomacy, as in the case where he facilitated a Japanese Little League team getting their visas in time to come to the Little League World Series. He is a man who can glibly throw spears at politicians from all parties and still have them love him. He receives 50 requests a week to appear at benefits for hospitals, churches, homes for juvenile delinquents. "He considers them all, then agonizes because he can do only a few." He does all this—and more.

I think the Hope-Crosby Road movies are very funny. Watching Hope's TV specials (or listening to his radio programs) I can take him or leave him; some of the jokes work, others don't, although the audiences of the times seem to have appreciated them. He stayed around too long, as his last shows attest; but then, how many performers really know when it's time to say goodbye?

Times change, as to tastes. One commentator on Teachout's article remarked that he didn't find Hope funny, but then he didn't think Dick Van Dyke or Bob Newhart were funny either. His taste ran more toward Seinfeld, to which another wrote that Seinfeld was old news, that he wasn't funny either. You can accept Teachout's thesis that Hope's main flaw was that he wasn't a "Jewish comedian," but my hunch is it as much more to do with our short-attention-span generations, where except for slights (real or imagined), nothing that happened more than 36 hours ago is worth mentioning. Hope forgotten? Yes, as are most of the Founding Fathers and U.S. presidents (well, perhaps Grant's Tomb was a little hasty), Johnny Carson, Peter De Vries, Sinclair Lewis, Jackie Gleason and—for the latest generation—even Jerry Seinfeld. Playwrights, poets, novelists, movie stars, television heroes, political leaders, religious figures; their time always seems to come and go, when a society doesn't care to remember its history.

Bob Hope may not be the funniest man in the world to modern ears, but in context he was at the top. He was a great humanitarian, an institution at the Academy Awards, a Godsend to the troops. You just don't forget someone with the body of work he has. Even if you don't respect his humor, you respect his accomplishments, and to the extent that he is forgotten, it says little about him—and a great deal about us.

l l l

No "Sullivan vs. The Palace this week; usually, it's because ABC's found some reason or other to bump The Hollywood Palace, but this time it's CBS', fault—Ed makes way for the network's annual showing of The Wizard of Oz, hosted by Danny Kaye, at 7:00 p.m. It's easy to forget that in the days before DVDs and VCRs and all-movie cable channels, the showing of a movie like The Wizard of Oz could be quite an event. In its early broadcast years, it was shown as part of pre-Christmas festivities, but starting in 1964 it was moved to January, which is where it is this year. I was surprised to learn, in a somewhat jumbled and repetitive article from the always-reliable Wikipedia, that the movie has never been shown on local television—it's always been broadcast either on an over-the-air network or on cable. I guess it's true that you learn something new every day if you're not careful.

Anyway, I digress, It's too bad Ed didn't show up for the battle this week, because it's the first anniversary of The Hollywood Palace, and to celebrate they've brought back the host of that first show, Bing Crosby. Bing welcomes his co-stars from his ABC sitcom, Beverly Garland and Frank McHugh, the King Sisters, ballet dancers Jacques d'Amboise and Catherine Mazzo, comedian Corbett Monica, the Three Rebertes acrobats, and Leonardo, who does some always-welcome plate spinning. Bing's joined for a skit by previous Palace hosts, including George Burns, Liberace, Cyd Charisse and Tony Martin, Gene Barry, Ed Wynn, Debbie Reynolds, Groucho Marx, Buddy Ebsen, Phil Harris and Bette Davis. I think I'd have to give the week to Palace even if Ed was on.

l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era. To be fair, though, those first few U.N.C.L.E. episodes really weren't that good, at least compared to when the show found its stride in the last part of the first season and throughout season two. For one thing, the episodes Amory references come from before the producers figured out that David McCallum was just as important to the success of the show as Robert Vaughn.* One contemporary critic commented that it was McCallum's presence that allowed Vaughn to become a more well-rounded character, rather that the generic superspy he was originally conceived as. That, and the fact that McCallum had tremendous appeal to the young female fans of the show.

*In the past I've commented that Robert Vaughn is the only man I know who can make even the hero look and sound smarmy.

In that sense, we can't really disagree with Amory's observation that "for all the fast pace and gimmickry, there just isn't enough charm." Even when the concept is a good one, as was the case with "The Double Affair," the execution is lacking. "But there was also scene after scene which seemed to be building up to something that never happened." Even when it does, he complains, you don't really care about the characters; he's sure one bad guy keeled over not from violent mayhem, but because " he was, we are certain, bored to death."

He does credit McCallum as being better than Vaughn, although not by much, but again - it would be interesting to see if Cleve revisits the series in a year or so. Not during the dreadful season three, when the show becomes a grotesque parody of Batman, but when the balance between thriller and spoof seems to be just right. By then, we feel, Vaughn and McCallum are doing just fine as Napoleon and Illya - and we think he might agree with that.

l l l

I'm often impressed by the narrow lead time some issues of TV Guide have; take G-E College Bowl, for example, in which the winning college returns the following week to defend its championship. The show airs live on Sunday afternoons, and yet week after week the name of the returning champion can be found in the following week's listing. Assuming the magazine comes out on Thursday or Friday, that gives it only a couple of days to get everything ready. Sometimes, however, especially in cases of the unexpected, we run into a listing for a program that never was. Such is the case this week.

New Orleans in the 1960s remained a racial tinderbox—one of the most segregated and racist cities in the South, according to some. In fact, just a couple of weeks prior, the Sugar Bowl (which began in 1935) had hosted its first game that included a fully integrated team (Syracuse University), a game which had come off without incident. The American Football League had scheduled the All-Star game for the city as a try-out for a possible expansion team; at the time, there were no professional franchises located there, and the NFL and AFL were competing for cities in the underrepresented South. However, as this excellent article points out, New Orleans was headed for a major black eye. Despite assurances by the league and city officials, black players were almost immediately subject to discrimination as soon as they arrived for the game:

[M]any of the black players were left stranded at the airport for hours when they arrived in town. Once in the city African American players were refused cab service and in some cases those who were given rides were dropped off miles from their destinations.

Other players were refused admittance to nightspots and restaurants, while nearly all were subjected to tongue-lashings and to a hostile atmosphere on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter while sightseeing. The situation became so uncomfortable for the black players who clearly felt unwelcome that most simply returned to their hotels.

Eventually, the twenty-one black all-stars—supported by many of their white teammates—voted to boycott the game if it remained in New Orleans. Panicked league officials, with little time to do anything else, were forced to act quickly. On Monday, January 11 - only five days before the game - AFL Commissioner Joe Foss announced the game was being moved to Houston. It was too late for TV Guide to do anything about it, but the Close-Up remains a reminder of the climate of the times, and of how long it took some things to change. I wonder how the announcers on the telecast addressed the situation?

l l l

Wednesday is January 20, and we all know what that means every four years - the inauguration of the President and Vice President of the United States. This year, President Lyndon Johnson will take the oath of office for his first full term, in circumstances quite different from those which existed when he became President on November 22, 1963.

For the first time since that date, the nation will have a Vice President, as Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey is sworn in, followed by LBJ himself. After a landslide victory over Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, it is a chance for Johnson to rejoice, to feel the sense of triumph denied him due to his sudden accession to the presidency. As one newsman commented—probably Edwin Newman; it has his puckish sense of humor—Johnson "looked as if he could dance all night, and probably did." And yet, I wonder if the nation had really recovered from JFK's assassination. It's only about 14 months since then, and just as news commentators compared Kennedy's triumphant inaugural trip down Pennsylvania Avenue to his solemn funeral cortege along the same route, it was bound to occur to more than one observer that LBJ's victorious parade could well have been—should have been—Kennedy's.*

*A brief political interjection: though I'm no fan of Johnson's politics, I've always felt compassion for the man considering how he was treated by so many of the Kennedy loyalists.

TV coverage of the inauguration is complete, beginning at 7:00 a.m. on NBC with Today, and continuing on CBS at 10:00 and ABC at 10:30, leading up to the oath-taking at noon, with musical performances by Leontyne Price and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, followed by the Inaugural Parade. That night, attention shifts to the four Inaugural Balls (and Johnson's all-night dancing), so big that even The Tonight Show is preempted in order for NBC to cover them.

Four years later, the scene will repeat itself, with a stunningly different cast of characters. Richard Nixon, thought to be cast into political oblivion, is now President; LBJ, harried and hated, leaves office after choosing not to run for reelection; Robert F. Kennedy, the heir-apparent to Camelot, is dead; Hubert Humphrey, four years a Vice President, barely misses catching Nixon at the end. Not for the first time, nor for the last, does one muse on how nobody possibly could have predicted it.

l l l

Let's see, it's been awhile since we've had a starlet of the week, hasn't it? Well, let's try Debbie Watson on for size.

Debbie, still 15 at the time this issue comes out (she turns 16 on January 17) is, in the words of "people who should know," one of the "it" girls—that is, whatever "it" is that makes someone a star, she has it. She's the lead in the sitcom Karen, one of the three programs that makes up the umbrella series 90 Bristol Court on NBC*, and even though that series only lasts a year, she'll rebound to star in the 1965-66 version of Tammy, based on the big-screen movies. In 1966 she'll take the place of Pat Priest in Munster, Go Home. And at this point, she is getting a kick out of the whole thing.

*The other two programs are Harris Against the World and Tom, Dick and Mary. Of the three, only Karen lasts the entire season.

She's naive, though, and hasn't seemed quite to understand what it means to star in a TV series. She's been late to a photo shoot, and she's skeptical that being an actress will change much about her life. These things aren't offered as criticisms, but pointed out to show just how green she is. And maybe that's why her career is so short. Her last entry in IMDb is an appearance on Love, American Style in 1971, and after that she retired to what has been by all accounts a relatively satisfied life. And there's nothing wrong with that.

A couple of weeks ago ABC telecast the United Nations drama Carol for Another Christmas, which strongly supports international interventionism, and at the time I mentioned there'd be more discussion to come. That discussion comes in the form of the Letters to the Editor section, which—unlike the reviewers—are strongly positive. Ruth Halfman of St. Louis writes to say she was "greatly moved," while C. Herbert Wolf Sr., who lives in Roswell, New Mexico, calls it the finest sermon he's ever heard, and adds that "it put the Christ in Christmas." George Oliver of Metairie, Louisiana thanks Xerox, writer Rod Serling, director Joseph L. Mankiewicz and ABC itself for "the best Christmas present of the year," and appreciates the lack of commercials.

Not everyone is so sanguine, though; George W. Coughenour of San Bernardino, California congratulates everyone involved for "a wonderful piece of Communist propaganda," and Frances K. Samuels of New Caanan, Connecticut complains that "Rod Serling laid the blame for all the world's wars and ills on the American doorstop."

Perhaps the most ironic letter comes from Linda Love of Pensacola, Florida. In its entirety: "My husband spent the last few months in Vietnam. After seeing this program I won't have to ask why. Thank God we Americans care enough for our fellow man to fight to free him from oppression." Why do I call it ironic? Well, the conventional wisdom, for what it's worth—certainly for Mr. Coughenour, as well as Daniel Grudge, the Scrooge-like character played by Sterling Hayden in the show—is that those who like the show and support the mission of the UN are nothing more than bleeding-heart activist liberals. And yet within three years, many of those same liberals will be marching through the street, chanting "What are we fighting for?" and Muhammad Ali is saying "I ain't got nothing against those Viet Cong." Even the UN turns against the war.

TV Guide says that letters are running "about 6 to 1" in favor of the UN series. I wonder, if they were to revisit those letter writers in 1968, how many of them would feel the same way?

Finally, a note from Richard Warren Lewis' article on the development of the ABC series Peyton Place. It is said that the idea to air the show twice-a-week was inspired by twice-weekly soap opera Coronation Street "that was aired on British television and earned huge ratings." I'm sure Lewis didn't mean to refer to Coronation Street in the past tense, as if it weren't on television anymore. It premiered on ITV on December 9, 1960, and at the time of this article had been on for just over four years.

Peyton Place, which debuted on ABC September 15, 1964, would run to June 1969, and then was resurrected for a daytime run on NBC in the early '70s. Coronation Street, on the other hand, remains a British institution, more than 60 years after its debut and still going strong, with over 10,000 episodes under its belt. Something which we can all only dream of. TV

She's naive, though, and hasn't seemed quite to understand what it means to star in a TV series. She's been late to a photo shoot, and she's skeptical that being an actress will change much about her life. These things aren't offered as criticisms, but pointed out to show just how green she is. And maybe that's why her career is so short. Her last entry in IMDb is an appearance on Love, American Style in 1971, and after that she retired to what has been by all accounts a relatively satisfied life. And there's nothing wrong with that.

l l l

A couple of weeks ago ABC telecast the United Nations drama Carol for Another Christmas, which strongly supports international interventionism, and at the time I mentioned there'd be more discussion to come. That discussion comes in the form of the Letters to the Editor section, which—unlike the reviewers—are strongly positive. Ruth Halfman of St. Louis writes to say she was "greatly moved," while C. Herbert Wolf Sr., who lives in Roswell, New Mexico, calls it the finest sermon he's ever heard, and adds that "it put the Christ in Christmas." George Oliver of Metairie, Louisiana thanks Xerox, writer Rod Serling, director Joseph L. Mankiewicz and ABC itself for "the best Christmas present of the year," and appreciates the lack of commercials.

Not everyone is so sanguine, though; George W. Coughenour of San Bernardino, California congratulates everyone involved for "a wonderful piece of Communist propaganda," and Frances K. Samuels of New Caanan, Connecticut complains that "Rod Serling laid the blame for all the world's wars and ills on the American doorstop."

Perhaps the most ironic letter comes from Linda Love of Pensacola, Florida. In its entirety: "My husband spent the last few months in Vietnam. After seeing this program I won't have to ask why. Thank God we Americans care enough for our fellow man to fight to free him from oppression." Why do I call it ironic? Well, the conventional wisdom, for what it's worth—certainly for Mr. Coughenour, as well as Daniel Grudge, the Scrooge-like character played by Sterling Hayden in the show—is that those who like the show and support the mission of the UN are nothing more than bleeding-heart activist liberals. And yet within three years, many of those same liberals will be marching through the street, chanting "What are we fighting for?" and Muhammad Ali is saying "I ain't got nothing against those Viet Cong." Even the UN turns against the war.

TV Guide says that letters are running "about 6 to 1" in favor of the UN series. I wonder, if they were to revisit those letter writers in 1968, how many of them would feel the same way?

l l l

Finally, a note from Richard Warren Lewis' article on the development of the ABC series Peyton Place. It is said that the idea to air the show twice-a-week was inspired by twice-weekly soap opera Coronation Street "that was aired on British television and earned huge ratings." I'm sure Lewis didn't mean to refer to Coronation Street in the past tense, as if it weren't on television anymore. It premiered on ITV on December 9, 1960, and at the time of this article had been on for just over four years.

Peyton Place, which debuted on ABC September 15, 1964, would run to June 1969, and then was resurrected for a daytime run on NBC in the early '70s. Coronation Street, on the other hand, remains a British institution, more than 60 years after its debut and still going strong, with over 10,000 episodes under its belt. Something which we can all only dream of. TV

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)