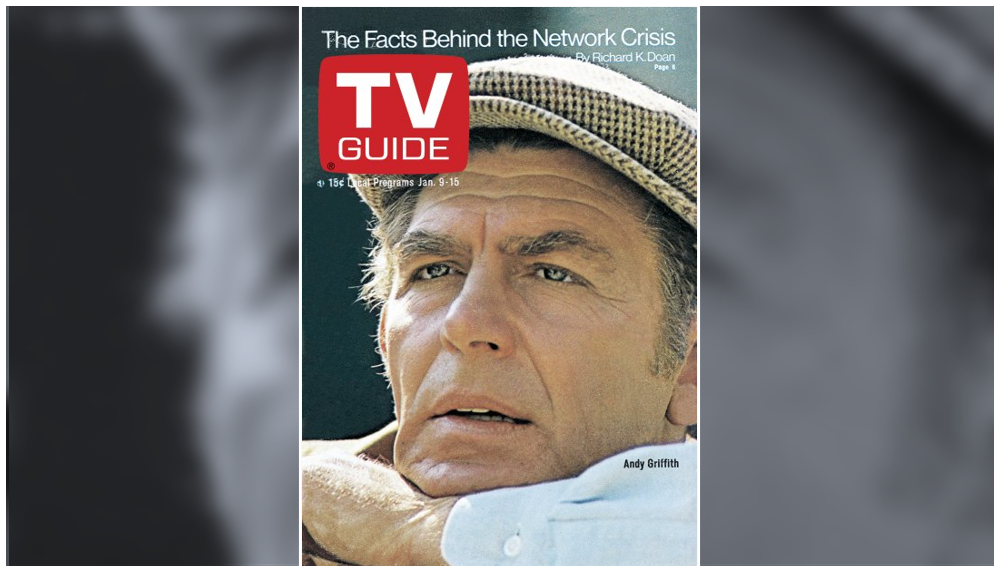

It's long been a contention of mine that the early years of the 1960s are really an extension of the '50s, and that the '60s as cultural phenomenon reach into the early '70s. However, as is the case with most theories, there are exceptions, and one of the clearest examples of how the decades differ is Andy Griffith. If this was a Matlock mystery, it might be called "The Case of the $3,500,000 Misunderstanding."

Bill Davidson's cover story does indeed tell a story, that of the beloved television star finding out you can't go home again, but if we're honest about it, that story really dates back to 1957, when Andy Griffith made a great movie called A Face in the Crowd, after which nothing would ever be the same. The movie made Griffith a star, but it left a deep scar in him as well; critics began to refer to him as "another Jimmy Stewart," and whether you agree with that assessment or not the fact remains that Jimmy Stewart never was sheriff of Mayberry (although he could be as homespun as anyone), and while The Andy Griffith Show made Griffith a millionaire and the undisputed star of CBS, it also left him craving another bite of that dramatic apple—a bite it seems he'll never get.

This would seem to explain his decision in 1968 to abandon Mayberry in favor of a five-year contract to star in at least ten movies for Universal, where they assured him he'd "be another Jimmy Stewart or Hank Fonda." The deal lasted but one year, and produced one movie (Angel in My Pocket), and when the studio asked him to do a comedy with Don Knotts, "That cut it," Griffith says. "I love Don, but teaming up with him again would be like going backwards."

And so his next step was, if not backwards, at least lateral—back to television, thanks to his longtime agent Dick Linke, in a dramedy called Headmaster. CBS was so excited at the prospect of getting their star back that they signed on to a series without a script, or even a scenario, for $3.5 million. Headmaster called for him to play "a stern but just high school principal," with the comedy left to others, but the Andy that audiences knew and loved clashed with the new Andy, the one "pompously moralizing with minsermons on such maxitopics as drug addiction and freedom of academic expression." The show was a bomb, and though Griffith's stature alone could probably have gotten the series a second season, both he and the network agreed to scrap it in favor of The New Andy Griffith Show, in which he returned to his rural roots as mayor of a small Southern town. There are hopes for the series as this issue goes to press, but alas, the new new Griffith show does even worse than the old new Griffith show, and before the year is out CBS is back to running reruns of Headmaster in the timeslot.

It's just one of several setbacks which will come Griffith's way: Adams of Eagle Lake, Salvage 1, and The Yeagers are all short-run series, and he'll make at least as many failed pilots. He remains popular and in the public eye due to his numerous TV-movie appearances, including some of those darker roles he craved. Finally, in 1986, he hits the jackpot again with Matlock, where he plays the down-home Southern lawyer, but with a sharp edge that had been missing with Sheriff Andy Taylor. The series runs for nine seasons, even longer than the original Andy Griffith Show.

But while it's always nice to go out on top, one can't help but think of his words when describing A Face in the Crowd. "I wish I could get a role like that again," he says in this article. "It'll come along." Success may return to Andy Griffith, but that one role he craves, that second bite of the apple, never does.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era. The problem plaguing August, according to Amory, is that "they want it both ways. A tough, hard-hitting, violent, beat-'em-up—but, of course, mustn't have too much violence, so, in at least two episodes so far, they give you, in the station house, a kind of second-degree third degree." Anti-establishment enough to attract "the kids," but not so anti that it turns the elders off. Stories that invariably feature two sides. And so on. Even the setting—large enough for big-city crime, small-enough that cases still involve August's friends.

Lest you think the producers are merely covering all the bases, Amory notes, "like every other show that ever set out to have it both ways, Dan August hasn't got it either way." The result is an unreal mishmash that usually leaves you with nobody to root for, or even identify with. As for Reynolds, "[t]hey are so careful to make him not one thing or another—not too superhero, for example, nor too bumbly—that they end up not making him anything. He is all wood and a yard wide." His co-stars "just trail around after Dan, trying to pick up the pieces of the plots and expositions." That is, those who aren't either invisible or irritating.

In fairness, Amory does find the good in Dan August, in that the show takes on, as we noted, difficult themes, ones that present both sides of an issue. "It does not do them particularly well, mind you, but it does undertake them." Alas, the old adage that the person who walks in the middle of the road winds up getting hit from both directions holds true for TV series as well: Dan August never sees August, going off in April 1971. It reappears in reruns only after Burt Reynolds' career takes off later in the '70s. Proving, I suppose, that no good deed goes unpunished.

On Sunday, the NBA and NHL seasons get underway on ABC and CBS. Now, if you're a sports fan, you might have thought the seasons actually began in October. But, you see, those games don't count—like the internet today, nothing happens unless it's seen on television. Back in the days before sports saturated the tube, the networks didn't pick up on hockey and basketball until after the football season had ended, and so with football all but over, it's time to move on to other sports. On Saturday, ABC kicks off the tenth season of the Professional Bowlers Tour with the St. Paul Open, televised live from St. Paul, Minnesota (3:00 p.m. ET), while the PGA tees off on CBS with coverage of the Glen Campbell Los Angeles Open (5:00 p.m. Saturday, 4:30 p.m. Sunday).

|

| The Juice and Jill St. John |

This provides us with a nice segue to some of the week's variety shows. We're past the era of The Hollywood Palace, and Ed Sullivan is preempted tonight by the Super Bowl show, but that doesn't mean we're without variety. Glen Campbell is enjoying Sunday evening success with his Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour on CBS (9:00 p.m.), and tonight his guests include Liberace, Neil Diamond, Larry Storch, Linda Ronstadt, and the winner of the aforementioned Glen Campbell Los Angeles Open. That's followed by Jackie Gleason's show (10:00 p.m., CBS); tonight's rerun stars Bing Crosby, Maureen O'Hara and Bert Parks in a Honeymooners-goes-to-Hollywood musical.

On Monday night Rowan and Martin (8:00 p.m., NBC) welcome Johnny Carson, Gore Vidal, and Los Angeles mayor Sam Yorty (an odd collection if ever there was one), and on Carol Burnett (10:00 p.m., CBS) the guests are Jerry Lewis and Leslie Uggams. Tuesday features The Don Knotts Show (7:30 p.m., NBC) with Lloyd Bridges, his sons Jeff and Beau, Nancy Wilson, and Tommy Roe (but no Andy Griffith, we might add.) The second half of the Knotts show overlaps with Hee Haw (7:00 p.m,. CBS), still on its network run, with Roger Miller, Peggy Little, and New York Yankees outfielder Bobby Murcer (?) leading the way. And we've got dueling shows at 9:00 p.m. on Wednesday, with NBC's Kraft Music Hall going up against ABC's Johnny Cash Show. On the former, "Alan King Plays the Games People Play" with James Coco, Anne Meara, and Mary Ann Mobely; the latter features Jane Morgan, Homer and Jethro, Bill Anderson, Gordon Lightfoot, and Jan Howard.

Thursday night features Flip Wilson (NBC, 7:30 p.m.), and an eclectic guest cast of Zero Mostel, Steve Lawrence and Roberta Flack. Meanwhile, do you remember that Jim Nabors left Gomer Pyle to host his own variety series? (Probably, except for some of you youngsters out there.) It ran for a couple of seasons and did very well, but it was included in the rural purge that claimed so many of CBS's other successful series. Anyway, Jim's special guest this week is Robert Goulet, along with Jim's regulars Ronnie Schell and Frank Sutton (8:00 p.m.). Of course, the crown jewel of Thursday's shows is always Dean Martin (10:00 p.m., NBC), and this week Deano has something for everyone, with Orson Welles reading from the Bible (I'll bet you thought he only did roasts), and Charles Nelson Reilly and Don Rice for comic relief. Finally, on Friday, This Is Tom Jones ends its two-year run, with Petula Clark as Tom's sole guest. (10:00 p.m, ABC)

It's interesting that even in 1970 people within the medium were predicting the eventual end of the networks, and it's a theme that will continue through this year of 1971. Some thought they'd be gone before the turn of the century; nearly all of them felt they'd have disappeared by now. The reasons are fairly simple: the dreck polluting the airwaves today, combined with the coming growth of cable television, something that nearly everyone knows is coming. In the first of a two-part analysis by Richard K. Doan, we learn the details of the gloom descending on network boardrooms.

There are a host of reasons for pessimism, to be sure: loss of revenue, due at least partially to the ban on cigarette advertising ($200 million annually); loss of a half-hour of prime time per night starting next year ($170 million in lost billing); a movement to ban commercials on Saturday morning cartoons (the biggest profit center other than soap operas and The Tonight Show); a prohibition of networks syndicating their old series to local stations ("lucrative"); increasing attacks from politicians, particularly Vice President Spiro Agnew; and that's just the tip of the iceberg. Says one insider at NBC, "Let's face it, we're as big as we're ever going to get. From now on it's a defensive action."

Donald McGannon, president of Group W, said the programming put out by networks is "not relevant to our times," and was a major backer of the FCC move to give a half-hour per night of prime time back to local stations. He felt the result would be "socially relevant, innovative and instructional or cultural" programs every night on all stations. The result, of course, has been syndicated game and talk shows and other such pablum. And there we have it, for just about every plan to reform television has failed. Greater network control of television programs, started as a response to the Quiz Show Scandals, has resulted in an increased emphasis on ratings, which in turn has caused programmers to dumb down their shows in search of that "lowest common denominator" programming. The salad days of the past, when the networks were rolling in money, have resulted in unrealistic profit expectations. As one executive points out, "what other business expects to return 45 [cents] out of every dollar to profit? And that's the return right now."

(In Group W's defense, it should be noted that in 1976, they launched Evening Magazine, called P.M. Magazine on non-Group W stations, which would run throughout the remainder of the 1970s and '80s, and included segments produced by local stations as well as the national content.)

We don't know what the second half of this article says about what all this means for the future of broadcasting and the effect on viewers, but we can make a few observations based on what we know today. Network television did survive the dismal predictions, at least for a little while. The growth of cable television reduced network ratings, true, but for awhile the networks seemed poised to survive. The attraction of cable in those days was mainly uncut movies, female nudity, sports, and news. Networks bought into cable networks, and those stations even became prime buyers of network syndicated programming. Once cable started producing its own original programming, however, the tide indeed began to turn. Before long the Emmys were dominated by cable series, and cable became a byword for quality. Then streaming video entered the picture, first through services like Netflix and Hulu, and then these services started producing original programming as well. The "cut the cord" movement became a real thing, though its long-term trend is still up in the air.

And so we have returned once again to the future of network broadcasting. Whereas the concerns of the '70s were based in part on fear of the future, today's worries seem more grounded in fact, in an analysis of what's happening right now. It's not just concern about network survival, either—it's the entire concept of television as we know it, for the cable networks stand to lose the most. Some even predict the networks could come out of this in better shape, at least in the short term.

One thing's for certain, however: the future of television has always been a matter of great speculation. Only now, we find ourselves asking if that future has finally arrived.

This week's starlet is Angel Tompkins, the typical ambitious actress, and Leslie Raddatz says don't bet against her when she talks about how she hates losing and likes beating the system. The hook Raddatz is using in his story is that Tompkins lives on the same street as Bob Hope, but it's not the neighborhood with the mansions—rather, she lives with her son in one of a row of tiny cottages for which she pays rent of $145 a month. It's every bit the rags-to-sort-of-richest story, coming from a broken home, with a childhood full of insecurities, a failed early marriage, a number of television credits to her name, and the determination to "work and improve."

Her credits continue into the '80s, and include a Playboy spread a year after this article appears, but in this household she'll always be best known for her too-infrequent appearances as technician Gloria Harding, Hugh Lockwood's (Hugh O'Brian) nemesis/love interest in the 1972-73 series SEARCH, which I'm currently reviewing with Dan Budnick on the Eventually Supertrain podcast. A pity she wasn't in that series more often; her character was one of great charm and spice, always looking to puncture Lockwood's ego while and the same time dispensing the information that helps save his neck. Ah, well; not the only lost opportunity in television history. She becomes heavily involved in SAG politics, and probably leaves a greater mark there than from her acting career.

She never becomes the star she should have been, but she's done better than most.

l l l

Finally, a woman who's a star by any and every definition of the word: Sophia Loren. There's no particularly good reason to include this, either in TV Guide or here, other than, well, Sophia Loren. She's not appearing on any program in the near future (although she's always been a hit on television), nor is she publicizing an upcoming movie. No, the reason we're here in Rome is simply to find out "what 'movie stars' look like these days, an era defined by "faded blue jeans and tie-dyed sweat shirts." The good news is that Miss Loren does not go in for this kind of clothing, at least not in public. "You must feel like a queen at that moment," she says. We'll leave you with these as parting shots.

TV

Finally, a woman who's a star by any and every definition of the word: Sophia Loren. There's no particularly good reason to include this, either in TV Guide or here, other than, well, Sophia Loren. She's not appearing on any program in the near future (although she's always been a hit on television), nor is she publicizing an upcoming movie. No, the reason we're here in Rome is simply to find out "what 'movie stars' look like these days, an era defined by "faded blue jeans and tie-dyed sweat shirts." The good news is that Miss Loren does not go in for this kind of clothing, at least not in public. "You must feel like a queen at that moment," she says. We'll leave you with these as parting shots.

TV

Mitchell,

ReplyDeleteYou made one small error. Andy did "Angel in My Pocket" for Universal, not Paramount. Hard to believe though that this film has never had a Home video release in its 53 year history.

Ah, I had high hopes that the mistake was in the article, but no such luck! Thanks--fixed.

DeleteThe era of premium pay (and streaming) is led by X-rated shows, as executives and critics have deliberately pushed shows that would not be allowed in a multiplex, which is sad because things you'd see in an adult film store are now being pushed as the next big thing on television.

ReplyDeleteThe prime-time access hour rule has become a major revenue maker for syndication. Barry-Enright (with Colbert Television) made huge revenue from 1978-84 with their pair of The Joker's Wild (which was tried as a CBS game show 50 years ago, as part of a trip that also included Gambit, and The New Price Is Right, the last of which has become CBS' major daytime revenue maker that since 1986 has made occasional primetime trips, now during sweeps or the dead periods when modern television shows take time off between December and the Super Bowl) and Tic-Tac-Dough. That era effectively ended after Jack Barry's death because of squabbling between Dan Enright and staff that led to Jim Peck being let go after Barry's death, and Wink Martindale leaving a year later. Meanwhile, Merv Griffin and the King brothers (King World), which had success with the weekly Dance Fever, went for it by making a syndicated version of Wheel of Fortune with greater prizes (no network television restrictions) in 1983, followed by reviving Jeopardy! (oddly, a $75,000 limit on winnings was imposed until 1990), which today make over $150 million annually for Sony in syndication, licencing, ratings, and foreign versions. Just this week, the Polish version of Jeopardy! completed its Tournament of Champions.

The syndication business is lucrative. The No. 3 syndicated shows is NFL games because of the league's rule that Amazon Prime, ESPN, and other games not airing on network television must be syndicated to a local broadcaster in the home and away markets of each team playing.