|

| Victor Bogorad |

I’ve been thinking a good deal about television lately, which perhaps isn't surprising to you given that I write about it here four days a week. For the last couple of weeks, I've focused on how television entertains, and why it must entertain. This week, I want to speculate on the effect that contemporary culture might have on classic television.

In talking about "classic" television, one of the questions we frequently face is: how do we define "classic"? Is it a show from before you were born? One that aired when you were a teenager? Does it have to be in black-and-white or not? There is no "right" answer, because the word—and the shows themselves—have an intensely personal meaning for each person. As I've said before, television is the most personal of media, and our relationship with the shows we watch bears that out.

But here's a question I don't think I've considered before, or at least not in the way that I'm going to pose it now, which is:

Are we ever going to be able to enjoy an old television series again?

The springboard to this discussion is an article by Carl Trueman at First Things entitled, "The Strange Fate of Hamilton and Harry Potter." (Now, there's a pairing you don't see very often.) The point of Trueman's perceptive article is, as he says in the lead paragraph, "moral relevance in the modern world [is] a cruel and fickle mistress." In other words, what works today doesn't necessarily work tomorrow.

You're probably familiar with some of these situations, programs such as Amos 'n' Andy that are no longer aired because the premise is supposedly objectionable, or out of touch with modern sensibilities.* In the case of Amos 'n' Andy, the show was still being aired in syndication in Minneapolis as recently as the early 1960s; CBS pulled it from syndication in 1966, and according to the always-reliable Wikipedia, it hasn't been broadcast regularly nationwide since, except for a run from 2012-2018 on the now-defunct Rejoice TV network. Like another banned classic, Disney's Song of the South, you can find Amos 'n' Andy if you look hard enough.

Trueman doesn't have to go back as far as Amos 'n' Andy, and that's part of the point he's making. Indeed, the examples are hardly ancient history:

Last week, Constance Grady at Vox noted how so much pop culture of recent vintage has dated so rapidly. Hamilton, the hit musical of 2015, now appears, in 2021, to glorify “the slave-owning and genocidal Founding Fathers while erasing the lives and legacies of the people of color who were actually alive in the Revolutionary era.” The TV series Parks and Recreation is now considered “an overrated and tunnel-visioned portrait of the failures of Obama-era liberalism.” And the Harry Potter franchise is now “the neo-liberal fantasy of a transphobe.”

The moral tastes of culture, Trueman notes, have always changed over time. "What is notable today," he points out, "is the speed at which they change and the dramatic way they repudiate the past." He cites the backlash to John Cleese's 40-year-old Hitler impersonations as an example of how things used to be, before a combination of social media and changing tastes condensed the timeline rapidly. "But now, jokes that were unexceptional five or ten years ago might well cost a comedian his career today. The moral shelf life of pop cultural artifacts seems much shorter now and the criteria by which they might be judged far less predictable." It must be exhausting to have to constantly monitor the offensiveness of such things.

Such examples of what people refer to as the cancel culture aren't limited to individual programs or movies, of course—the Harry Potter stories find themselves victims not so much due to what they contain, but because of the personal views of J.K. Rowling. Numerous stars have found themselves ousted from television shows or movies because of their vaccination status; setting aside the legality of such acts, there's no question that you're more likely to find favor with the dominant arbiters of social acceptability if you've received the jab (although this, pray God, may be changing). It's true that this is hardly new in the entertainment world; try finding Bill Cosby or Robert Blake on television, or Kevin Hart hosting the Academy Awards. What is different, though, is the speed with which such blacklisting is taking place—in this case, happening virtually in real time.

Trueman identifies the real problem as that "the moral tastes of popular culture are just that: tastes, and thus subject to fashion and, in our social media age, to easy manipulation. Society has no solid foundation on which to build its moral codes." While most people don't give this much thought—and would probably laugh derisively at those who do—Trueman says the inevitable result is a world, "with no agreed upon moral compass and marked by a deep suspicion of any attempt by any one group to make its truth normative, out of fear that the result will be oppressive and unjust.

With that as the backdrop, let's return to my initial assertion that we might have a hard time being able to enjoy old TV shows. Yes, it's pretty easy to find Parks and Recreation on streaming services or in DVD, but imagine that the show's crime against society was more egregious, picking on a group or issue destined by some future ruling class to be protected. "Today race theory, not feminism, might be the critical theorists' soup du jour," Trueman writes, "but this will prove no more lasting than previous iterations of the voice of the oppressed. Intersectionality witnesses to that fact; and those who live by the sword of critical theory can expect at some point to die by the same." Under such constant flux, "today’s virtuous icons are tomorrow’s vile scoundrels."

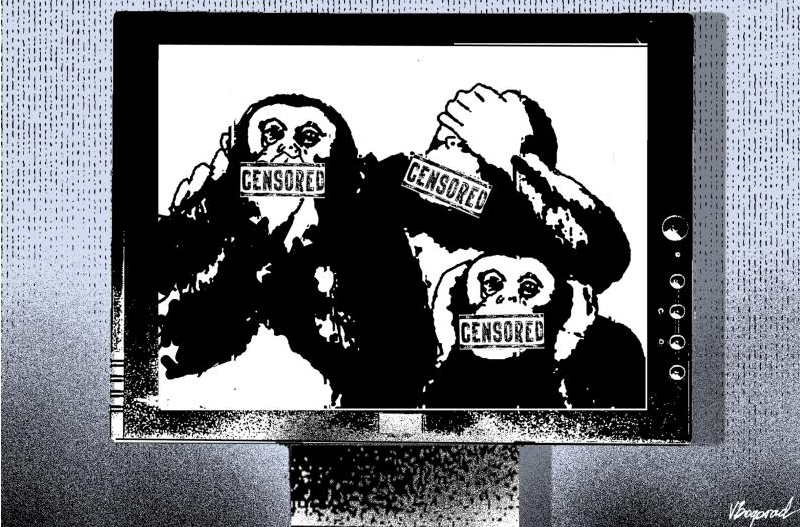

Under these circumstances, will you be allowed to enjoy old television shows, or will they have to undergo some kind of cultural CAT scan to determine whether or not they're suitable for a general audience? Look no further than YouTube for examples of content being censored; I recall awhile back that the app was banning documentaries about Hitler because he was such an offensive guy—notwithstanding that the content of many of these programs was devoted to demonstrating how Hitler was such an offensive guy. The powers-that-be were still worried that some Hitler cult could use the footage to drum up support for der Fuhrer.

Anyone can be offended by anything, of course; I'm sure there's someone out there who finds the early seasons of My Three Sons offensive because it proves that boys can be raised in a healthy environment without the presence of a woman. But—and here's where this ties in to my previous two essays—if television shows persist in being controversial, in being political, in advocating particular social stands, then they run an increasing risk of saying the wrong words, portraying the wrong deeds, winding up on the wrong side of this week's history. Post hoc, of course.

We've complained for a long time that network executives keep new shows on too short a leash, refusing to give them enough time to grow and cultivate a following. What we're experiencing here is the cultural equivalent, a kaleidoscope of opinions and mores that makes the fluttering of a hummingbird's wings appear in slow motion by comparison. For, as Trueman concludes, "Today, moral tastes have too short a shelf life for that. Indeed, embracing the moral spirit of the age is now more akin to having a one-night stand—and that with somebody who kicks you out of bed in the morning and calls the police." And you can probably watch it on TV that night. TV

I don't buy the idea that cancel culture is recent. After all the Spanish Inquisition cancelled about 4,000 people permanently. It's the internet that has made way too much information flow through everyone so that we never slow down long enough to discuss and reach a consensus. It's also given a haven to people who love Hitler. What a nightmare.

ReplyDeleteObviously keeping your own copies of shows when you can get them is the only way.

Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!