October 31, 2022

What's on TV? Friday, November 3, 1967

Happy Halloween, everyone! We've arrived in late 1967, and you can see that the penetration of color into network programming is almost complete. There are still a few daytime shows, mostly on ABC, that continue to be made in B&W, as are some reruns of series from earlier in the decade, but for the most part the transition has been completed. From now on, the only shows not in color are the aforementioned reruns, occasional live news remotes, and local programming. I'm not quite sure when the majority made the move to color broadcasting their locally produced shows (like the news), and you'll notice that some stations lack the ability to replay color programs that were recorded from a different time or network. These stations would probably be shocked at how much more advanced the equipment is in today's home than what they had. That's progress, at least in the quality of broadcasting if not the quality of programming. This week's guide is the Minnesota State Edition.

October 29, 2022

This week in TV Guide: October 28, 1967

We've got a Cleveland Amory 2-for-1 this week, and that's a hard offer to pass up, especially when Cleve has the cover story. Your level of interest will vary depending on how you feel about Hollywood society.

Our story begins with Hollywood itself, which Amory says is "only a dream," and like other mythical dreams, it was discovered more or less by accident, but most certainly by D.W. Griffith, who'd been sent by the Biography company to make the movie In Old California. Griffith had settled in downtown Los Angeles, but soon found everything he needed in Hollywood. He was soon joined by Cecil B. DeMille, who wound up in Hollywood after having tried to film a western in Flagstaff, where he had found "a raging blizzard and not a single Indian, for free, for hire or for reservations." Like Griffith before him, DeMille found Hollywood to his liking, and soon, "month by month, year by year, the dream factory grew." Anyone could give it a try; as Lewis Selznick once said, "The motion-picture business takes less brains than anything else in the world." (A statement that has yet to be disproved?)

Amory goes on to relate the stories of the stars who made Hollywood glamorous, "the boys who would be gods and the girls who would be goddesses." There was Mary Pickford, who at age 16 had been discovered by Griffith for $5 a picture; "Several years later she herself drew up her contract, which called for $10,000 a week, plus half the profits of her pictures." No wonder she was in at the beginning of United Artists. Clark Gable arrived in a train from Portland, "with four handkerchiefs, two clean shirts, and $2 in cash." He married up, and ten years later he was a star. So did Lucille LeSueur, who waited on tables at age 9, did homework for classmates at 14, did some time in the chorus line, and wound up being Joan Crawford. Greta Garbo was, according to Louis B. Mayer, "too fat," but she made it anyway. Gloria Swanson took baths in a solid gold bathtub, Dolores del Rio drank from a golden chalice, Tom Mix had a drawing room with a fountain that sprayed water in all sorts of colors. I guess, if that's your thing.

Mansions were all the rage. Marion Davies had three, including a 14-room bungalow. Harold Lloyd's boasted the world's largest Christmas tree, with 50,000 ornaments. (Now that's my kind of guy.) At Pickfair, home of Pickford and her husband, Douglas Fairbanks, practical jokes were in; Fairbanks had the dining chairs wired so visitors (even royalty) could be given the "hot seat." And the excess wasn't limited to architecture, either; in promoting an upcoming picture, Sam Goldwyn's advertising department came up with the tag line that We Live Again combined "The directorial genius of Mamoulian, the beauty of Sten and the producing genius of Goldwyn [naturally]" to make "the world's greatest entertainment." Said Goldwyn, "That is the kind of ad I like. Facts. No exaggeration."

Part two of Cleve's chronicle, to appear in the following week's issue, promises to reveal how the Hollywood giants saw themselves and others. They can't do any better than Fred Allen, who once observed acidly that movie stars even wore sunglasses to church. "They're afraid," he said, "God might recognize them and ask them for their autographs."

l l l

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup.

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup.Sullivan: Scheduled: actress-singer Polly Bergen; pianist Peter Nero; dancer-choreographer Peter Gennaro; ventriloquist Senor Wences; comedians Myron Cohen and Richard Pryor; the Cowsills; and juggler Jean Claude.

Palace: Host Bing Crosby presents comic pianist Victor Borge, singers Roger Miller and Gail Martin, comedian Paul Lynde, Fred and Mickie Finn's ragtime group, and the United Nations Children's Choir.

Unlike many weeks, the lineups here are light on vaudeville acts; the only listed one belongs to Jean Claude on the Sullivan show. Otherwise, things look pretty evenly matched; I've never been a particular fan of children's choirs, especially the UN choir with the kids all in their "native" costumes (I always enjoy how they put the Arab states next to Israel, no doubt hoping to help create peace for future generations). On the other hand, all that really does is offset the Cowsills. And with Roger Miller, Dean Martin's daughter Gail (who can really sing), and Victor Borge, the Palace has a crowd-pleasing lineup—enough so that it gives Palace the win by a phonetic exclamation point.

Unlike many weeks, the lineups here are light on vaudeville acts; the only listed one belongs to Jean Claude on the Sullivan show. Otherwise, things look pretty evenly matched; I've never been a particular fan of children's choirs, especially the UN choir with the kids all in their "native" costumes (I always enjoy how they put the Arab states next to Israel, no doubt hoping to help create peace for future generations). On the other hand, all that really does is offset the Cowsills. And with Roger Miller, Dean Martin's daughter Gail (who can really sing), and Victor Borge, the Palace has a crowd-pleasing lineup—enough so that it gives Palace the win by a phonetic exclamation point.

l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era. Cleveland Amory's second appearance this week takes us to the world of the television sitcom, and the new CBS series He & She. It's become fashionable over the years to regard He & She as a sitcom that was ahead of its time, a witty and sophisticated precursor to such adult shows as those starring Mary Tyler Moore and Bob Newhart. It's kind of surprising, therefore, that our man Cleve is not so bullish on He & She, viewing it as one that "at best is mildly amusing high camp—and, at worst, is wildly confusing low bunk."

For Amory, He & She is farce, played completely and entirely for laughs, but for farce to be successful, "you must give your audience such a steady rolling barrage of laughs that they forget you are robbing them of all that is nearest and dearest to them—which is believability." To accomplish this, the producers have surrounded our winsome starts, Dick and Paula (Richard Benjamin and Paula Prentiss) with a supporting cast of "supposedly screamingly funny regulars," each of whom, according to Amory, is at best a one- or two-joke caricature doing the same one or two jokes each week. "By the 15th time they have done the same thing, we are ready to scream—but unfortunately not with laughter."

Amory picks out Jack Cassady as the worst offender, "directed so far over [the top] that he is actually fascinatingly infuriating." Cassidy's character, the egotistic actor Oscar North, has of course widely been considered the template for MTM's egotistic anchorman Ted Baxter (Ted Knight), one of television sitcom's iconic characters. As for the leads, he views Benjamin as fine, although "his nasal voice is a pretty harsh irritant," while Prentiss, whose character is one of the first working wives on television, is "a lovely sight, but she is obviously an acquired taste." Apparently, if He & She was ahead of its time for viewers, it was also ahead of its time for Cleveland Amory. But sometimes Cleve reassesses his reviews at the end of the season; I wonder if he did here as well?

l l l

Before reality television, before daytime chatfests, before Barbara Walters asking you what kind of tree you would be, there was a somewhat more demure, now mostly forgotten program called Personality, a game show which ran on NBC from 1967 to 1969 and, according to Edith Efron, caused its celebrity guests to "park their inhibitions."

|

| Personality, with host Larry Blyden |

The questions come from a master questionnaire written by Stewart, consisting of hundreds of questions "of a personal nature," and they come across as something of an existential Dating Game. Many of them are about sex: "What do you think about sex?" "What's the best way to keep monogamy from turning into monotony?" Others are ethical or fanciful: "If you slept during the next 10 years, what's the first thing you'd like to know when you woke up?" "What do you think is man's greatest weakness?" Finally, there are what Efron terms "intensely personal questions": "What causes you to feel weak in the knees?" "If you had to describe your own personal kind of hell, what would it be like?" I knew things would get interesting!

Although I tend to be one who looks at these celebrity confessionals and shouts "TMI!" there's no question that the format seems to deliver on what it promises. The questions "force people to use their imagination, they force them into deep self-expression. They make people express things they have on their minds and hearts which they don't ordinarily express," Stewart says. "They often say after an interview, 'My God, it's like going to a psychiatrist!'" That may sound like hype, but the answers are surprisingly self-revelatory. When asked, if reincarnation was real, how she would like to come back, Zsa Zsa Gabor replied, "Like I started but without all the mistakes I made." Robert Vaughn, asked the quickest way for a woman to reach his heart, said, "adulation toward me and total silence." And, perhaps most revealing is Henry Morgan's answer when asked if anything is a fate worse than death: "Living."

Efron is impressed by the insight shown by some panelists when asked to guess how the celebrity answers. Skitch Henderson, for instance, correctly deduced Sammy Davis Jr.'s definition of love from the three options given him by reflecting on Davis's relationship with wife Mai Britt: "I think the sort of thing he would say about love would be associated with Mai, so he would say: 'Looking across the room at your wife and just smiling.'" He was right. And when it comes to guessing how the public viewed them, the celebs were split; Henry Morgan was delighted to find he'd correctly predicted that the public, when asked if Morgan were president of a bank, would demand heavy collateral on all loans. On the other hand, Bill Cullen was disappointed when he was told that the public, given the choice of casting him as a clever lawyer, a mad scientist, or the fellow who doesn't get the girl, chose the last option. He'd hoped they'd see him as the clever lawyer.

As far as I could tell, there are a couple of Personality episodes on YouTube; you can see one of them here, with Jack Cassidy, Joan Rivers, and Flip Wilson on the panel. (The other episode, which is uploaded in two parts, appears to be from the same week.) Take a look at it and see if you think something like this would work today.

l l l

There's plenty more to watch this week, starting with Saturday's rematch of last season's college football Game of the Century, as Michigan State travels to Notre Dame to play the Fighting Irish. (1:30 p.m. CT, ABC). Unlike last year's showdown of undefeateds, each side has lost twice coming into this year's matchup. The difference in the two teams' fortunes: after Notre Dame wins 24-12, they run the table and finish the year 8-2, ranked #5 in the nation; Michigan State, on the other hand, will win only once more, en route to a disappointing 3-7 record. As integration eliminates the pipeline that brought black players to northern schools, it will be decades before Michigan State is a national contender again.

Sunday's highlights include the TV premiere of Hud (8:00 p.m., ABC), which Judith Crist calls "extraordinary," featuring a towering performance in the title role by Paul Newman, "the soulless man who not only remarks that he doesn't give a damn—but doesn't." Patricia Neal (Best Actress), Melvyn Douglas (Best Supporting Actor) and James Wong Howe (Best B&W Cinematography) won Oscars, and the movie has been considered a classic almost since its 1963 debut. If that sounds a little too intense for you, you might prefer the delightful Hayley Mills in Pollyanna, spread over three weeks on The Wonderful World of Color (6:30 p.m., NBC).

Next, it's a Monday Night Football trial run, with the Green Bay Packers and St. Louis Cardinals facing off from St. Louis (8:30 p.m., CBS). It's established TV history that CBS turned down the rights to MNF in 1970, leaving ABC to pick up the pieces; I've often wondered how much CBS regretted that move over the years.

Tuesday's Jerry Lewis Show (7:00 p.m., NBC) features what sounds like a truly atrocious premise: a trio of Jerry, Don Rickles. and Dorothy Provine singing "Bosom Buddies." Maybe it isn't as bad as all that—I'm a fan of Dorothy's going back to The Roaring '20s, and she can do it all—but it's probably best to keep one's expectations low. Better yet, check out tonight's episode of The Invaders (7:30 p.m., ABC) in which David Vincent tries to infiltrate a conference of world leaders that may mask an alien plot. This would explain a lot about our world today, wouldn't it? And at 8:00 p.m., NBC presents its first made-for-TV movie of the season, Stranger on the Run, with Henry Fonda as a murder suspect being hunted for sport by a sheriff and his two deputies.

Jack Benny is the host on Wednesday's Kraft Music Hall (8:00 p.m., NBC), with an eclectic lineup: Liberace, singer Astrud Gilberto, concert violinist Michael Rabin, rock band the Blues Magoos, and two comedians who can also play musical instruments: the aforementioned Henry Morgan on violin, and Morey Amsterdam on cello. I started to wonder why Don Rickles wasn't included, but have no fear: he's Ben Gaszara's client on tonight's Run for Your Life (9:00 p.m., NBC). Don plays a comedian charged with assault, and we'll leave it at that.

We've seen numerous examples of how Golden Age dramas were fleshed out into theatrical films—Requiem for a Heavyweight, Marty, Patterns, 12 Angry Men—and this week we see another, with the TV premiere of 1962's Days of Wine and Roses (Thursday, 8:00 p.m., CBS), which Judith Crist calls "a grim and graphic depiction" of alcoholism, and boasts top performances from Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick. Speaking of top performers, I don't know how good tonight's episode of Cimarron Strip (6:30 p.m., CBS) is, but you can't beat the heavyweight guest cast, which includes Richard Boone, Andrew Duggan, Robert Duvall, Morgan Woodward, and Ed Flanders. And on F. Lee Bailey's interview show Good Company (9:00 p.m., ABC), Lee visits with Nobel Prize-winner Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

On Friday, the Bell Telelphone Hour (9:00 p.m., NBC) travels to England for highlights from the Aldeburgh Festival, hosted by one of the 20th century's most notable composers, Benjamin Britten. Later, on WTCN's 10:00 movie, James Stewart stars in The Spirit of St. Louis, the story of Charles Lindbergh and his famous flight. I mention this only because I'm fairly sure I watched this when it was on back then; I've seen it again since, but when you're a kid, you don't forget the feeling of being able to stay up late watching TV because it's not a school night, and the 10:00 movie was, if I'm not mistaken, sponsored by the auto dealership Downtown Chevytown, which of course used Petula Clark's song as its theme. Ah, the things that stick in your mind.

l l l

As I've said before, we're all about linkage here, and since Cleveland Amory brought up Paula Prentiss earlier, it would be very, very wrong to ignore the fashion layout she does in this week's issue. Here's, she's displaying four fall outfits designed by Viola Sylbert for Albert Altus. not that you'd notice, but the plastic and Lucite chair was designed by Phil Orenstein for Mass Art. Paula Prentiss and Richard Benjamin were married in 1961, and often performed together. They're both still around, still married, 61 years later.

What was it Cleve said about her being an acquired taste?

l l l

This week's MST3K alert: Kitten with a Whip (Friday, 11:10 p.m., KDAL). "A young girl who has escaped from prison threatens the career of a politically ambitious man." Ann-Margret, John Forsythe, Peter Brown. The only MST3K episode that I wasn't able to finish watching even once, not even to see them give this movie its well-deserved scorn.

Honorable mention: Attack of the Mushroom People, a 1964 Japanese sci-fi flick, never made it but should have. "A yachting party, cast ashore on an uncharted island, encounters a horrifying fungus." Anybody for a horror reboot of Gilligan's Island? That'll really give the Professor something to do. TV

October 28, 2022

Donald Pleasence delivers in "The Changing of the Guard"

|

| The headmaster delivers the news to Professor Ellis Fowler (Donald Pleasence) in "The Changing of the Guard" |

The following is part of The Devilishly Delightful Donald Pleasence Blogathon, running this weekend at many of your favorite blogs. Be sure to check our sponsors, Cinematic Catharsis and Realweegiemidget, throughout the weekend for the latest posts. "Around the Dial" will return next Friday—same time, same channel.

The quote, and the Antioch experience, obviously made an impression on one of its more renowned graduates, Rod Serling. Serling used it in a script which he wrote for his television series, The Twilight Zone, and not long after completing the script, he accepted a teaching position at Antioch. And it is that quote, mounted on the base of a statue of Horace Mann and read by a character named Ellis Fowler, that serves as the fulcrum for the episode, "The Changing of the Guard." Not surprisingly, the success of the episode will depend on the performance of its star, Donald Pleasence.

There is a tendency, not without merit, to think of "The Changing of the Guard" as a Christmas episode of The Twilight Zone, given that the story takes place over the course of one day—December 24, Christmas Eve—but in fact it aired on June 1, 1962, the thirty-seventh and final episode of the series' third season. It has the usual trappings of a seasonal story, though: a wintery landscape of a small New England prep school, Christmas music on the radio, a plot that, in the wrong hands, has the potential for tear-inducing sentimentality. And, by the end of the story, you might find yourself reacting that way. But, as you'll see, there are good reasons why this episode appears on The Twilight Zone and not, say, the Hallmark Channel.

l l l

|

| Professor Fowler and his boys |

Following the final bell, Fowler is summoned to the headmaster's office, where the headmaster (Liam Sullivan) gently but firmly informs him that, after 51 years of teaching at the school, the board of trustees has made the decision not to renew his contract for the spring; they feel that someone younger might be more relevant, "more beneficial to the students." Despite the headmaster's efforts, the news shocks Fowler to the core, leaving him reeling and speechless.

The scene shifts to his home, where he looks through old school yearbooks, remembering all the boys who've come and gone through his classroom. "They all come and go like ghosts," he tells his housekeeper, Mrs. Landers (Philippa Bevans). "I gave them nothing at all. Poetry that left their minds the minute they themselves left. Aged slogans that were out of date when I taught them. Quotations dear to me that were meaningless to them. I was a failure, Mrs. Landers, an abject, miserable failure. I walked from class to class an old relic, teaching by rote to unhearing ears, unwilling heads. I was an abject, dismal failure—I moved nobody, I motivated nobody. I left no imprint on anybody." He smiles sadly. "Now, where do you suppose I ever got the idea that I was accomplishing anything?" He leaves, telling her that he is going out for a walk; afterward, she discovers to her horror an empty gun holster in his desk drawer.

|

| A professor, a statue, and a gun |

One by one, they begin to tell Fowler of how he had impacted their lives. Most of them were killed in wartime, but one boy (Russell Horton) died from radiation poisoning while researching cancer treatments; he recites lines from a poem Fowler had taught them, Howard Arnold Walter’s "My Creed":

I would be true, for there are those who trust me;

I would be pure, for there are those who care;

I would be strong for there is much to suffer;

I would be brave for there is much to dare;

I would look up, and laugh, and love, and lift.”

|

| Voices from the grave |

Fowler returns to his home a changed man. He reassures the worried Mrs. Landers that everything is now all right, and he is content to hand things over to a newer generation of teachers. Hearing the sound of carolers outside, he opens the window and finds his students singing; they wish him a Merry Christmas and move on. Fowler smiles, this time not from sadness or bitterness, but quite contentment. He now understands how his life had changed the lives of his boys, and how they have validated his in return. As Serling says in his closing narration, Professor Fowler "discovered rather belatedly something of his own value."

l l l

There are obvious parallels between "The Changing of the Guard" and two other Christmas classics, Frank Capra's movie It's a Wonderful Life, and Charles Dickens's story "A Christmas Carol" (choose any version you want). Like these stories, "The Changing of the Guard" deals with the supernatural appearance of ghosts; like them, the protagonist leaves the encounters a profoundly changed man, with a new outlook not only on the future, but the past. As George Bailey discovered in It's a Wonderful Life, no man is a failure who has friends; Fowler learns that the same is true for those who have impacted the lives of others—in short, everyone.

Anyone seeing "The Changing of the Guard" for the first time, and I hope there those of you out there who will get just such an opportunity, will admire for many things about it: the writing, the makeup, the photography, the performances of the secondary players, use of the stock music. But one overriding feature will grab you and stay with you long afterward: the performance of Donald Pleasence as Professor Ellis Fowler.

|

| Professor Fowler and Mrs. Landers |

Serling's script for "The Changing of the Guard" is simple and elegant; for reasons I'll get to shortly, the subject matter was very close to him. Given all that, as Twilight Zone Companion author Marc Scott Zicree writes, the role of Fowler is not an easy one; Pleasence himself was only 42 at the time of filming and was heavily made up by William Tuttle to look the part of a man at least 30 years older. And considering Serling's writing style, the part could come across as "talky and clichéd." A.V. Club reviewer Zach Handlen echoes the importance of Pleasence's performance to the success of the ghost story: "If Fowler’s gentleness isn’t obvious, and if his shift into depression wasn’t sincere and heartbreaking, then everything else falls apart into sentimental treacle."

With that, Pleasence's performance is magnificent. As Handlen notes, there's "a fundamental fragility to all of Donald Pleasence’s work, a kind of raw, gentle vulnerability," even in a character like the Bond villain Blofeld. Here, Pleasence is tasked with bringing out that vulnerability in a man, closer to the end than the beginning of his life, who is suddenly and unpleasantly forced to contemplate his life's accomplishments, knowing that there will be no opportunity to create more, and finding his account (he thinks) to be empty. "Pleasence manages to convey all of this in his early scenes, and the shock, when it hits, is effectively heartbreaking." Brian Durant, writing at The Twilight Zone Vortex, calls Pleasence's performance "as moving and honest as any the show ever saw."

|

| Rod Serling |

With this as the background for "The Changing of the Guard," there's no question as to its impact on the atmosphere that pervades the story. It is moving without being sentimental, delicate without being cloying, and ends on an optimistic note that feels genuine rather than contrived. It has the right touch of the supernatural—who's to say, after all, that on the eve of a day dedicated to the coming of God as man, that those ghosts weren't angels, come to deliver the message of life to a weary man just as they had, nearly two thousand years before, to a weary world? In a article I wrote several years ago on this episode and its relationship to the season, I quoted the seldom-performed third stanza of the Christmas carol "It Came Upon a Midnight Clear," and I still think it sums things up quite well, especially the performance of Donald Pleasence:

O ye beneath life's crushing load,

Whose forms are bending low,

Who toil along the climbing way

With painful steps and slow;

Look now, for glad and golden hours

Come swiftly on the wing;

Oh rest beside the weary road

And hear the angels sing.

Perhaps, just perhaps, "The Changing of the Guard" is a Christmas episode, after all. And if that seems a little far-fetched to you, just remember: this is the Twilight Zone. TV

October 26, 2022

The best of worlds, the worst of worlds

|

| (left to right) Stephen Young, Luke Halpin, and Carl Betz |

One of the things I most like about Judd, for the Defense (along with the powerful performances each week by Carl Betz) is how the scripts take on controversial issues without necessarily being polemical, demonstrating through misdirection and unexpected plot shifts that things are not always as simple as they seem. (You could argue that there's a little too much misdirection, but that's how good mysteries work.) Combine this with the occasional episode that stubbornly refuses to wrap everything up in a bow at the end, and you get a series that probably should have lasted more than two seasons. (But then, not being a network executive, what do I know?)

Something else that Judd has in common with the best shows of its era is the ability to illustrate, unironically and without the filter of contemporary mores, how society has changed over the decades—sometimes evolving, frequently devolving, but seldom remaining static. Case in point is the first-season episode "The Worst of Both Worlds," a story that's both timeless and subject to a completely different interpretation than it would have had when originally broadcast on March 8, 1968.

The Cliff Notes version of the plot: Judd and his associate, Ben Caldwell (Stephen Young) are called in to defend 17-year-old Kenny Carter, Jr., who was sentenced to 3½ years in the county juvenile home for stealing and wrecking a sports car belong to a family for which he'd done odd jobs, the wealthy and influential Merritt family. The man driving the car that Kenny hit was seriously injured in the crash.

At first, it seems a straightforward case of injustice being done to the boy; talking to Ben at the county home, Kenny (Luke Halpin) insists that "I didn't admit anything because I didn't do anything," and that "because of the way they ask you the questions in court, if you answer 'no,' it turns out you're a liar; if you answer 'yes,' you're guilty." At the hearing, he was without benefit of counsel (a lawyer wouldn't have been available for three weeks, and upon suggestion of the judge, Kenny waived his right), and no transcript of the hearing was kept, due to cost. The juvenile officer, Frank Austin (Frank Marth, so we know he's going to be the bad guy), whose duty is to act in Kenny's best interests, maintains that the boy's rights were always kept in the forefront of the investigation.

Convinced that the boy's rights were denied, Judd applies for a Writ of Habeas Corpus to get Kenny out of the home, and seeks a new hearing for him. Based on the circumstances, a judge agrees to both. It's then that the first complication occurs, when Austin reveals to Judd that Kenny had assaulted Mrs. Merritt prior to stealing the car. Austin's motive in acting as he did in the first hearing was to prevent this from coming out--"holding back the kind of charge that could ruin his life"; as it was, he would have been a delinquent in the juvenile home, "but you had to come along and open Pandora's Box." Kenny denies the assault, but Judd and Ben know he's holding back. After Mrs. Merritt (Pippa Scott) testifies in court and confirms that an assault happened, Kenny finally, reluctantly tells them the truth: he and Mrs. Merritt had been having an affair, she had tried to prevent him from leaving the house because he wanted to go on a date with a girl his own age, and (because she'd been drinking) she fell and hit her head, sustaining the injuries that Kenny was supposed to have inflicted. He then took the car to get a doctor for her, and wrecked it because the brakes were faulty. All this time he'd been trying to protect her, but now that she's turned on him, he has no choice. After undergoing a withering cross-examination from Judd, Mrs. Merritt finally breaks down and admits the truth, and the charges against Kenny are dismissed.

After the judge has ruled, while Kenny is being comforted by his family, Judd confronts Austin in the corridor, and we come to the plot point around which everything revolves:

Mr. Austin, you owe me an explanation. Didn't you know what was going on between Kenny and Mrs. Merritt?She told me about their struggle. When she was still upset enough to be telling the truth. Later on, I could see she carefully did not tell her husband. So I could make a pretty good guess.And you didn't say a thing in your official capacity?My official capacity was to protect the kid, n ot to let him get smeared the rest of his life. Of course, I didn't know the whole story, particularly that brilliant council would take over the case.Mr. Austin, I did nothing more than any competent lawyer would have done. The point I wish you would see is the injustice of trying so many of these kids in juvenile court without lawyers and calling that 'protection of the young.'Well, how would you protect them? By feeding kids into the machinery of the ordinary criminal courts, where nobody cares what happens to them? Look, do you really think you did this kid any favors by getting him off scot-free? Without any disciplinary correction?He's not legally guilty of anything.He was carrying on with a married woman. He lost his head, he took a car he couldn't handle properly, and he caused a very serious crash. Now, let me ask you this, Mr. Judd. How would you feel about seeing some other lawyer get him off, if you were the man he ran into?

|

| Judd wins again—or does he? |

If one were to air this episode, unchanged, on a contemporary program, we'd probably be shocked. First of all, Mrs. Merritt, having seduced a minor, would be considered a sexual predator, and even if she didn't do any jail time, she'd go into the sex offender registry for sure. (What would that have done to a socially prominent family?) Kenny would be seen as a victim, not someone carrying on an affair with a married woman. His name would be kept confidential; even though word would spread in a small town like the one in which the story occurs, it's not going to follow him around on his record. Far from recommending "disciplinary correction," a judge would probably order counseling for him; as for taking the car, under the circumstances he acted not out of malice or criminal intent, but as a confused and abused boy who didn't know what else to do. In short, he's not a delinquent, but a boy taken advantage of by an older woman who should have known better. Austin likely would have been sacked had he proceeded the way in which he did and would have left both himself and the city wide open to civil charges. The entire denouement would have flipped, and Judd would have had an even stronger case for demanding that the legal system do more to protect juveniles from adult predators.

That's the way it is. That's not the way it was. At the risk of identifying myself once again as old, I can say that when I was in high school, none of us boys would have considered Kenny a "victim"—we'd have called him lucky, and each one of us were probably hoping the same thing would happen to us—minus the accident, of course; it's never any fun doing something you aren't supposed to be doing unless you get away with it. And we wouldn't have seen him as having been taken advantage of, he scored. Of course, that's what happens when you think with your hormones instead of your head, and that's why teenagers (or those who've never matured beyond their teens) shouldn't be running the world.

I'm certainly not suggesting that things were better back then, nor am I saying we're wrong to view things differently today. It probably suggests we should look at situations like this on a case-by-case basis. But "The Worst of Both Worlds" functions not only as entertainment, but as that time capsule I'm always talking about, presenting us with a look at how society was—not in retrospect, not seen through 21st century-tinted glasses, but the way it actually was at the time. If you want to study societal evolution, you can certainly do worse than this. TV

October 24, 2022

What's on TV? Tuesday, October 26, 1954

I don’t know why, but one of the things that always intrigues me in these issues from the mid-1950s is when a show’s sponsors is mentioned in the listings, as if it were a member of the cast or crew. It doesn’t even have to have its name in the title of the show; I wonder if they paid for the privilege? I thought I’d include those this week, so you can see how prevalent it is. Keeping the accent on the local, WMAL has a talk show hosted by Frank Small, Jr.; what do you want to bet that, at least once in a while, it was called “Small Talk”? And then there are the personalities that went on to national success: Jim Simpson, who does the sports on WTTG, was a superb and popular announcer on for many years at NBC and ESPN, particularly on football. John Rolfson, their 11:00 p.m. newscaster, would eventually go to ABC as a correspondent. Ron Cochran, the newscaster on WTOP, becomes the anchor of the ABC evening news. Of course, when you work in the Baltimore-Washington area, you get noticed—especially if you’re good.

October 22, 2022

This week in TV Guide: October 23, 1954

A few years ago, someone left a comment regarding this weekly feature that said, in essence, "why so few issues from the 1950s?" It was a good question, as most questions from all of you are. After all, issues of TV Guide from the 1950s don't necessarily cost any more than from any other era, unless the person on the cover went on to become really famous. I suppose it's a combination of things: first, that not having been alive during the 1950s, I'm not able to offer any personal experiences to augment the stories that these issues tell. Second, as we all grow older, fewer and fewer of the programs from the Fifties create the kind of pop culture impact that make them worthwhile to those of you reading them.

Or at least that's what I might have thought. However, over the last two or three years, I've made a conscious effort to include more TV Guides from the decade of the Fifties, and I've found that a good story is a good story regardless of when it happens; and also, that there are plenty of things from the Fifties that merge perfectly well with the culture of today. This week's issue is just such an example.

l l l

Walt Disney is known as one of Hollywood's great creative geniuses. His two greatest creations, "The Mouse" and "The Duck" (as he refers to them) have become an established part of American folklore. As a studio head, he's right up there with Mayer, Zanuck, Selznick and Warner. He's also known within the industry as a shrewd, perceptive businessman, and we'll see proof of that this week with the premiere of his new series, Disneyland, on ABC.

One of the questions being asked is "why," as in why Disney has chosen to become the first studio boss to produce a weekly television series. It's not for the money the show will generate; on the contrary, he expects to lose money on the actual show. No, the answer lies with 160 acres of barren land in Anaheim, California, 15 minutes from Los Angeles, which Walt purchased last May. On 60 acres, he plans to build (at a cost of $9,000,000) "what will undoubtedly be the most magnificent amusement ever constructed in this or any other country." (The other 100 acres, the unbylined article notes, "will become a picnic-parking area.")

Like the show, the park will be called "Disneyland," and like the park, the show will be divided into four segments: Fantasyland, Adventureland, Frontierland, and The World of Tomorrow. By the time Disneyland opens next July, an aide confides, "there will be hardly a living soul in the United States who won't have heard about the Disneyland amusement park and who won't be dying to come see it." Television, he concludes, "is a wonderful thing."

l l l

If you're wondering what to watch Sunday night, oh, say around 9:00 p.m. Eastern, you have one choice—and if you don't like it, you're pretty much out of luck.

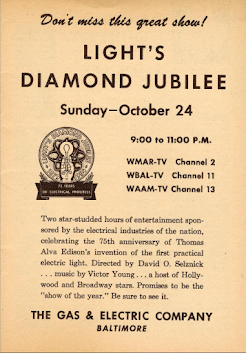

You see, we happen to be celebrating the 75th anniversary of light. Yes, I know you probably thought light went back much farther than that, perhaps as far back as the first day of Creation. You know, all that "Let there be light" stuff. That's just a detail, though; we all know that light really began with Thomas Edison's invention of the electric light, which he demonstrated to the public in 1879 and patented in 1880. (Yes, I know that others have a claim to inventing incandescent lightbulbs as well, but this isn't the History Channel. For that matter, the History Channel isn't the History Channel anymore, The point is, we're not going to debate the origins of the lightbulb here, unless I run out of other things to write about.) Now, 75 years later, David O. Selznick (speaking of movie moguls) is producing a two-hour variety special, Light's Diamond Jubilee, to air on all four networks, at a cost of $750,000, sponsored without commercial interruption by General Electric (along with over 300 companies from the electrical industry).

Joseph Cotton serves as host, with a glittering guest cast featuring Helen Hayes, Walter Brennan, George Gobel, Thomas Mitchell, David Niven, Eddie Fisher, Judith Anderson, Brandon de Wilde, Guy Madison, Kim Novak, Dorothy Dandridge and Lauren Bacall. And in case you still don't think Selznick's serious, included is a filmed tribute to Edison by President Eisenhower.

And just how do you celebrate the creation of electric light? Well, here are a couple of samples of sketches included in the show:

- "A Kiss For the Lieutenant," by Arthur Gordon. The buddies of a young Air Force lieutenant dare him to ask a beautiful girl for a date. Guy Madison, Kim Novak.

- "The Girls in Their Summer Dresses," by Irwin Shaw. On a warm Sunday morning in November, Mike and Frances Loomis are walking in Greenwich Village. But all Mike can do, it seems, is admire the pretty girls as they pass. Lauren Bacall, David Niven.

This kind of network-spanning broadcast wasn't completely unprecedented back in the day; a similar program, General Foods 25th Anniversary Show: A Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein, had aired on all four networks in March, and if I'm not mistaken, Jacqueline Kennedy's White House tour aired simultaneously on CBS and NBC, with ABC showing it at a later time. I suspect that today, the only time we'd see something like this (outside of news specials) is for a charity telethon.

As for how the show went over? Robert at the always-excellent Television Obscurities reports that New York Times critic Jack Gould gave it a generally favorable review (“a striking cavalcade of the American individual” and “a remarkable theatrical achievement"), but Broadcasting was much harsher in its assessment, calling it, "(1) a free plug for pleasant but elderly clips from Hollywood shelves; (2) an array of disjointed scenes whose waste of writers, actors and money perhaps surpassed any previous mish-mash in television history; (3) examples of bad taste in pitting amorous scenes against faith and hope; and (4) further proof that Hollywood’s hackneyed press agentry and program formats are bad television," which sounds about right to me.

Considering the lede this week, one is forced to ask the question: how much better might Light's Diamond Jubilee have been like had it been produced by Walt Disney?

l l l

Speaking of anniversaries, there's a full-page ad in this week's issue celebrating the 7th anniversary of Baltimore's WMAR, Channel 2. It's still around, with the same call letters; in this issue it's a CBS affiliate and would remain so until 1981, when it moved to NBC for 14 years; it's now an ABC affiliate. I mention this because there's such a sense of wonder as well as satisfaction implicit in the ad; WMAR started out in 1947, virtually the dawn of American television. (It was the 14th commercial television station in the United States.) What an exciting time to be involved in a new medium! Who would even know if this television would succeed? And here they are, seven years later, still up and running, still broadcasting seven days a week, with some even in color! It's quite a story when you think about it—no wonder they're proud.

l l l

What else? We've looked at a couple of longish pieces, so let's take a quick trip around the dial and see some of the rest of the week's highlights.

DuMont has exclusive coverage of Saturday night NFL games, and tonight at 8:00 p.m. it's the Philadelphia Eagles vs. the Pittsburgh Steelers. (Steelers 17, Eagles 7) Opposite that, The Jackie Gleason Show welcomes the Honeymooners back in an hour-long adventure (8:00 p.m., CBS). At 9:00 p.m., it's another colorcast of the monthly Max Liebman Presents (NBC), with the musical comedy "The Follies of Suzy," starring Steve Allen, Dick Shawn, and Parisian singer Jeanmarie.

NBC celebrates United Nations Day (yes, there still is such a thing) on Sunday with a special concert from the General Assembly Hall at the UN (2:30 p.m.), with Charles Munch conducting the Symphony of the Air and the Schola Cantorum, and speeches from New York Mayor Robert Wagner, UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold, and Eleanor Roosevelt. See what electricity hath wrought? And on Ed Sullivan's Toast of the Town, guests include dancer Carol Haney, singers Robert Merrill and Pearl Bailey, jazz combo the Treniers, and the acrobatic team of Vivien & Tessi. (8:00 p.m., CBS)

Monday gives us two of the Golden Age's prestige anthologies: first, Robert Montgomery Presents (9:30 p.m., NBC) tells the story of a young Southern lawyer-politician arrested on suspicion of the murder of his secretary; the story features E.G. Marshall, and wouldn't it be great if he was playing the suspect's defense attorney? (The young Lawrence Preston adventures!) Incidentally, the IMDb entry for this story describes it as "The effects of television coverage on justice are highlighted as facts get distorted along party lines and the cameras cover the 'event' inside and outside the courtroom." Sounds rather relevant on several levels, don't you think? I'd rather like to see that sometime. Meanwhile, our other drama, Studio One (10:00 p.m., CBS) stars Polly Bergen in a mystery "set in the Paris salon of designer St. Pierre." Oui.

Another anthology, Studio 57 (Tuesday, 8:30 p.m, DuMont) caught my attention for another reason. It might be a great episode or it might not, but considering our subject matter this week, how can you pass up a story that takes place at "a new kind of amusement park" called "Kiddieland"? Answer: you can't. Which reminds me that Wednesday brings the premiere of Disneyland (7:30 p.m, ABC), and Walt wasn't kidding when he said he wanted to make this show different. Tonight's episode begins with a trip to Disney's Burbank studios, followed by the beloved Mickey Mouse short "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" from Fantasia, and then a look at Kirk Douglas, Peter Lorre and James Mason on the set of the upcoming Disney epic 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

CBS counters NBC's Max Liebman spectacular on Thursday with the second Shower of Stars presentation, "Lend an Ear," (8:30 p.m.), a TV adaptation of the hit 1948 Broadway musical, starring Edgar Bergen, Charlie McCarthy, Mortimer Snerd, and Effie Klinker. Oh, and Sheree North, Gene Nelson, Joan Tyler, and a special appearance by Mario Lanza. That's followed by Four Star Playhouse (9:30 p.m., CBS), which (as you probably know) comes from Four Star Productions, the four partners being Dick Powell, Charles Boyer, David Niven, and the star of tonight's episode, Ida Lupino. She plays a schoolteacher investigating her own nephew's conduct and trying to figure out the rest of the story. The cast includes Hugh Beaumont, but the nephew's name is neither Wally nor Beaver.

There was a time, believe it or not, when Columbia University used to field a big-time college football program. No, really; they won the 1934 Rose Bowl, defeating Stanford 7-0.* The coach of that team, Lou Little, is still Columbia's coach, and he's Edward R. Murrow's guest Friday on Person to Person (10:30 p.m., CBS), as they discuss the football scene. Ed's second guest is the great Marian Anderson, who in January will become the first black singer to perform at the Metropolitan Opera, in Verdi's Un ballo in maschera. Marian Anderson had quite a career and quite a life—we'll have to talk about it sometime.

*A star of that Stanford team was Bob Reynolds, who after a couple of years in the NFL went into the broadcasting business, winding up as President of Golden West Broadcasting and part owner of the California Angels baseball team. His business partner in these ventures? Gene Autry.

l l l

This week's MST3K alert is a doubleheader: Jungle Goddess (Thursday, 1:30 p.m., WTTG). Two pilots go to Africa in search of a missing heiress. George Reeves, Ralph Byrd, Wanda McKay. Radar Secret Service (Thursday, 9:30 p.m., WTTG). Uranium ore is stolen. John Howard, Adele Jergens. It all puts me in mind for a char-broiled hamburger sandwich and some French-fried potatoes. TV

October 21, 2022

Around the dial

We're on to a new Hitchcock Project at bare-bones e-zine, as Jack looks at the output of Helen Nielsen, starting with the season five episode "Letter of Credit," with Robert Bray as a mysterious stranger in search of—what? You'll just have to watch and find out.

At Cult TV Blog, John continues his review of Hammer House of Horror with one of the series' most popular episodes, "The Two Faces of Evil," which makes very effective use of many horror tropes. It involves a hitchhiker, and you know that's always a promising start to a horror story.

David takes on the fad of retconning characters and events from classic television—in this case, it's the sexual preference of Scooby-Doo's Velma. Leaving the ideological aspects of this aside, it speaks to something I've criticized for a long time: our inability to view the past through anything other than a contemporary filter.

I've always enjoyed Michael Rennie; even so, there's a part of me that wishes his version of Harry Lime in the TV series The Third Man had been played by the original third man, Orson Welles. At Silver Scenes, we get a series that Welles did appear in, albeit as host only: Orson Welles' Great Mysteries. I suspect it was just the right amount of work for Welles.

Paul returns to the world of the telemovie at Drunk TV with his review of The U.F.O. Incident, "the marvelously creepy 1975 NBC made-for-TV sci-fi docudrama depicting real-life couple Betty and Barney Hill’s supposed 'alien abduction' in September, 1961." Did the abduction really happen? As always, you be the judge.

Finally, at A Shroud of Thoughts, Terence takes us back to The High Chaparral, the 1967-71 NBC Western that was revolutionary for its time, with Latinos making up 50% of the show's characters. It was a tough, gritty series, much more so than most of its Western contemporaries, and of course it had one of TV's great themes. It's a good note to end on, no pun intended. TV

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)