Imagine, if you will, that you’re a member of an organization—a society, let’s call it. Membership in the society is exclusive, by invitation only, and its purpose is to place its members in positions of influence in business, politics, finance, and academia, so you were greatly honored when you were invited to join. To be a member is a privilege, but not one you can share with others; not only can you not tell your colleagues, your friends, your family, even the very existence of the society is a secret. Through the years, you’ve attained the wealth and power that was promised, but there’s a catch: in return for the advantages you’ve been given, the society may call on you one day to return a favor, one consistent with the status you’ve attained. It’s an offer you won’t be able to refuse, and you know what that means, because once you become a member of this society, there’s no backing down, no way out.

Is it the World Economic Council, the Trilateral Commission, the Freemasons, the Illuminati?

Or is it the Brotherhood of the Bell?

l l l

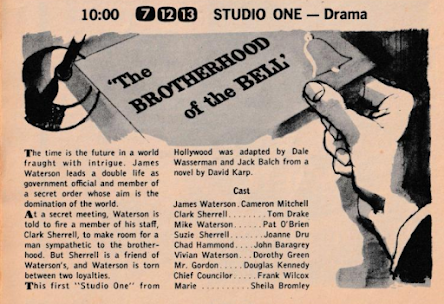

David Karp’s 1952 novel, The Brotherhood of Velvet, has been adapted twice for television under the title The Brotherhood of the Bell: once for Studio One on January 6, 1958, with a script by Dale Wasserman and Jack Balch; and again on September 17, 1970, for CBS’s Thursday Night Movie, this time produced and written by Karp himself. Despite differences in each of the three versions, the story is essentially the same: a decent man caught in a trap between his duty to an organization to which he has belonged for his entire adult life, an organization that has played a role in everything he has accomplished; and his duty to himself, his moral code, and his individuality.

The Brotherhood of the Bell, a society of men who graduated from the exclusive College of St. George in California, is presented as a singular honor, reserved for the best and the brightest. Its members are among the most powerful and influential men in the world, the elites of business, finance, academia, and politics. (When a new member comments that he’s now part of the establishment, he’s told, “We are the establishment.”) To be a member of the Brotherhood is to be set for life—professionally, personally, financially. There a catch, however: in one of the Brotherhood, members must pledge “absolute obedience and absolute secrecy,” and promise to do whatever is asked of them if they’re called upon to do a favor—no questions asked.

At the time, it was generally believed that the Brotherhood was based, at least in part, on Yale’s Skull and Bones society, an organization that has included many of the world’s leaders in, well, business, finance, academia, and politics. Its members have included U.S. presidents and presidential candidates, cabinet members and Supreme Court justices, publishers, corporate executives, and intelligence agents. Two of its members were George W. Bush and John Kerry, who faced each other in the 2004 presidential election; in his autobiography, Bush described Skull and Bones as “a secret society; so secret, I can't say anything more,” a description that both Bush and Kerry reiterated when asked by Tim Russert on Meet the Press.

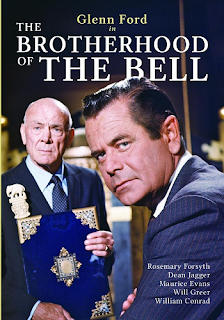

In the book and the Studio One production, our protagonist, Jim Watterson (played by Cameron Mitchell) “lead[s] a double life as government official [with the State Department] and member of a secret order whose aim is the domination of the world.” In Karp’s 1970 version, which is available on YouTube and DVD and which we’ll be using as the primary reference point, his name is Andrew Patterson (Glenn Ford), a respected professor working at a prestigious institute. In either case, he’s about to find out just what it costs to “belong” to the Brotherhood of the Bell.

l l l

|

| Dean Jagger (L) and Glenn Ford |

He has been assigned to prevent a close friend and colleague of his, Dr. Konstantin Horvathy (Eduard Franz), from accepting a deanship at a college of linguistics—a position that the Brotherhood has reserved for one of their own. Patterson is given a list of names of agents who helped Horvathy defect to the United States from behind the Iron Curtain, and is told to blackmail Horvathy by threatening to reveal the names of these agents (virtually guaranteeing their deaths) unless he declines the position.

Already apprehensive about the assignment, Patterson tries desperately to convince Horvathy to turn down the position; when he refuses, he hands Horvathy a copy of the list and tells him what he will be forced to do. Horvathy, a political refugee and lifelong opponent of communism, is shocked by Patterson’s revelation and feels betrayed by his old friend; rather than buckle under the threat, he commits suicide.

Horvathy’s death has a profound effect on Patterson, who knows that it was his pressure that caused the suicide. Patterson is sickened by his role in the death of his friend, and how the Brotherhood (with his cooperation), has taken away his humanity, he falls into a depression that is, what? Self-loathing? Suffocating guilt? A desire for revenge? The hope of redemption? All four?

In order to scourge himself of the effects from his membership with the Brotherhood, Patterson becomes determined to bring down the Brotherhood. He first confesses, and I think that’s the right word, to his wife Vivian (Rosemary Forsyth) about his involvement with the Brotherhood, as a way to explain the depth of his guilt. She suggests he talk with her father, Harry Masters (Maurice Evans), a powerful real estate tycoon with a knack for knowing the right thing to do. Taking Patterson’s story seriously, Masters introduces him to Burns, a federal agent who tells assures him that the government is aware of the Brotherhood, and takes the instructions and list of names from Patterson to use in the investigation.

So far, so good. But when Patterson goes back to the location where he met the agent, he finds there is no agent and no sign of the office in which they met. He contacts the agency (obviously the FBI, although not referred to by that name), and they tell him they don’t have any agent Burns. Patterson, increasingly alarmed by this turn, tells them to call Masters to confirm his story, but his father-in-law denies any knowledge of their conversation or the meeting with Burns, and suggests that his son-in-law is on the verge of a mental breakdown due to recent events.

The pressure on Patterson mounts. the foundation financing the Institute eliminates his department, putting him and everyone else who works with him out of a job. He flies to San Francisco to confront Harmon and threatens to expose him, but Harmon accuses him of ingratitude toward the Brotherhood and then delivers the crushing blow: it is because of the Brotherhood that he’s had had every job, received every fellowship, even met and married his wife. They even arranged for the construction company owned by Patterson’s father Mike to receive important contracts, making him a millionaire. “You have never competed for one thing in the 22 years since you took your oath at sunrise,” he tells Patterson, and while it’s vital to his belief in himself to think otherwise, deep down he fears it’s true. The media ridicules him and the DA refuses to investigate; today they’d call him a Conspiracy Theorist, and accuse him of wearing a tinfoil hat.

|

| Patterson tells Vivian to "get out" |

Patterson reaches the nadir when he appears on a local talk show to discuss the Brotherhood and is humiliated by the host (William Conrad at his malevolent best; think of a cross between Morton Downey Jr. and Jerry Springer). Even more demoralizing is his discovery that the only people who take his accusations seriously are crazies and other conspiracy buffs. Patterson touches off a brawl in the studio, and winds up in jail.

l l l

We probably ought to pause for a moment here and take stock of where we are.

Earlier, I mentioned differences in the three versions of Brotherhood of the Bell. In Karp’s novel and the Studio One version, Watterson (the Patterson character) works for the State Department, and is asked to fire his assistant and friend, Clark Sherrell and replace him with a member of the Brotherhood. The betrayal is that much more personal; Sherrell is not just a colleague, but Waterson’s assistant. Further, the evidence which they want Watterson to use against Sherrell is that he engaged in homosexual activity when he was a teenager. It’s a charge that’s very much of its time; both the communists and the anti-communists were known for using the homosexual angle in blackmail. Not having seen the Studio One version of Brotherhood, I don’t know if 1950s television would have gone there; since the names and premise are the same as in the book, I wouldn’t be surprised that it was some sort of sex scandal such as infidelity that was substituted.

(Incidentally, that 1958 Studio One production is said to be set in the near future: 1976. That would have been the Bicentennial year, the 200th anniversary of American independence. Is there a message to that, a reminder of what the country was founded on?) And despite the lurid paperback cover, the issue of sex is incidental to Karp’s story; if anything, it’s used as a metaphor for what it means to be a man—to be independent, to think for yourself, to stand on your own two feet and make your own life. Having just found out that none of his accomplishments have been due to his own efforts, Watterson has been, in a sense, emasculated. This same feeling is accomplished through other means in the 1970 production, but the net result is the same: a hollowed-out man, a man at his most vulnerable.

l l l

One of the most tender of all human vulnerabilities is the secret, and there is a reason why so many of us are so sensitive to it. Whether it be the diary of a teenage girl, the pseudonymous writings of a blogger, or the innermost confidences we share with a best friend, a secret exposes our most intimate thoughts and provides something of a window into the human soul: the hopes and fears and aspirations, but also the guilt and the wrongdoing and the unmasking of the truth. One of the reasons why the Catholic Church maintains the inviolability of the Seal of Confession is that reconciliation with God demands nothing less than complete, total honesty regarding sin, a candor that can be achieved only through its confidentiality.

Is it any wonder, then, that the thought of having these secrets exposed in public, whether to anonymous strangers, co-workers, or our own family and friends, chills our bones and fills us with an inexplicable dread? Even reality stars, who often seem to have no secrets whatsoever (nor any shame), use their shows at least partly to maintain control over the revelations of those secrets. Just look at what happens when some frenemy spills the beans: tears, screaming, and slap fights abound. And let’s face it, they still have secrets. Listen to what they admit, and then ask yourself how embarrassing must be those things they wouldn’t admit. (And while you’re at it, ask yourself as well if you don’t think them capable of doing those very things.)

We've gotten used to losing privacy in the name of convenience; what's security when compared to being able to have Siri take care of your needs just by saying the word. But the thought of an organization that as a file on you, filled with those secrets that you'd rather never see the light of day—that seems to cross a line for people (unless, of course, you're the one gathering the information). We’re outraged, offended, filled with rage. “You have no right!” we say. But in the very next instant, we’re overcome by dread and fear. What if someone were to find out? The secrets could be trivial embarrassments, law-breaking admissions, or something in-between; it might even be something that’s not your fault, but is difficult to explain. It makes no difference. It’s why blackmail never goes out of for style, and private detectives never go out of business. (It’s also why so many blackmailers wind up being murdered, at least on television.) Many people—maybe most—would do anything to keep those secrets from becoming public.

There’s one thing that we understand, though: there’s something wrong about an organization that collects and uses this kind of information. It is itself a secretive organization: a government agency, a public safety department, an organization filled with nameless, faceless bureaucrats, a human resources department; and it trafficks in all kinds of personal information, from your race to your "gender identification" to your vaccination status. This information could cost you the chance at a job, a loan, a business transaction; they won't really tell you how it comes into play, and the fact that they deal in secrets while remaining secret themselves is the icing on the cake. The people in charge of these organizations may use various rationale to justify their actions: national security, for instance, or public safety, or the ever-popular diversity. They may say that their goals are noble ones, such as the public good, or the survival of the planet; like your parents, they may say that it hurts them more than it does you. But, when they explain it to you this way, they expect you to understand that they’re only threatening to expose you in the name of a higher good. There’s nothing personal about it. It’s even for your own good, and if you don’t understand this, you’re just being selfish.

Or even worse, they’ll start a whispering campaign against you, one that gets louder as you resist them. They’ll accuse you of the worst possible mental illness known to man: being a conspiracy believer. Conspiracy becomes the dirty word of all dirty words, as if the mere suggestion means nothing you say matters.

l l l

And now the ending. One reviewer suggests that for the 1970 production, “apparently some idiot network executive made writer Karp tack on a schlocky hopeful ending”; a review of the book suggests a certain ambiguity; “Is it truly a plot or has Jim lost his mind and imagined it all as a result of paranoid schizophrenia?” Again, it would be interesting to know how Studio One brought the story to a conclusion, but I suspect it would be closer to the 1970 ending; television shows of the 1950s weren’t much for ambiguous endings, but it’s not impossible. But let’s discuss the ending we have, not the endings we lack.

Patterson is bailed out of jail by a most unlikely person: his boss at the Institute for the Study of Western Civilization, Jerry Fielder (William Smithers). Patterson has suspected Fielder of being part of the Brotherhood as well, but now it turns out that Fielder has been doing some investigating of his own, and has found that Patterson has been blacklisted from working for any other academic institutions. He believes Patterson’s story about the Brotherhood, but tells him he must find another member who can verify its existence.

In desperation, he returns to St. George, to Dunning, the man he sponsored for membership at the movie’s opening, and pleads with Dunning to join him—to bring down the Brotherhood for his own good as much as that of the world. “You’ve either got to be at war with them or you’re in their service!” he says. “Come with me and you’re free of the Brotherhood!” At first it appears that Dunning’s loyalties will remain with the Brotherhood, but as the movie ends, he joins Patterson at the airport, apparently enlisting in his campaign.

l l l

It's difficult to know where paranoia begins and ends in a story like this, one that’s equal parts Kafta and Koestler. (The Brotherhood of the Bell has been described variously as anything from a political thriller to a horror story.) One way of looking at it is to see it everywhere: Dunning only appears to join Patterson, but in reality he’s there to keep an eye on him, to eliminate him as a threat to the Brotherhood. But that’s far too cynical for me, and besides, it’s not consistent with the way the scene is played. Dunning has pledged himself to the Brotherhood; Patterson himself is the one who has brought him in. And now Patterson is telling him, in effect, that everything was a lie, that the Brotherhood is an evil organization determined to control the key sources of power in the world. That’s a hell of a shock for anyone to have to absorb; under the circumstances, Dunning’s hesitancy is all too real.

How would we react in such a situation, being asked to turn against an organization we’ve so recently joined, an organization which promises us everything—an organization which Patterson himself built up in prestige? Would we dismiss Patterson and his story as the ravings of a crazy man?

Or would we consider the alternative, that everything Patterson says—about the Brotherhood and about its control over us—is true? Would we be afraid to join Patterson, or afraid not to join him.

It’s that fear that organizations like the Brotherhood count on—and themselves fear.

l l l

In addition to writing seven novels under his own name, David Karp went on to a successful career as a writer for television; besides his script for the 1970 version of Brotherhood of the Bell, he wrote for series from The Untouchables and The Defenders (winning an Emmy for writing in 1965) to I Spy and Quincy, and created the legal dramas Hawkins (starring James Stewart) and The Storefront Lawyers. A recurring theme in his work, as Philip Boakes points out in a forward to one of his Karp’s novels, is “the pressure on the individual to conform,” whether that pressure be applied from the state (as in his script for the Playhouse 90 drama “The Plot to Kill Stalin,” or from society itself in the sense of prestige and position.

In 1955, Karp adapted his novel One, written in 1953, for Kraft Television Theatre. (It was also made into a British TV production the following year.) Described as a “political fantasy” in TV Guide and “dystopian fiction” by others, the story concerns a future society “on its way to a self-proclaimed perfection which consists in dissension having been rooted out and every citizen identifying his or her own interests with those of the ‘benevolent State.’ In order to achieve this aim, an enormous state apparatus has devised a sophisticated system of surveillance, subtle forms of re-education and, if necessary, brainwashing.”

What sets Karp’s stories apart is their timelessness, their ability to offer us a shadowy, shape-shifting antagonist with the ability to adapt to any given period in history. The fear and paranoia, the mysterious masters pulling all the strings—contemporary critics have been quite right to liken it to the McCarthy blacklists and the Stalin purges, but we can also see in in the elite with their secret societies, the government infiltration of organizations deemed “threatening,” the ever-expanding surveillance state, the suffocating conformity of the corporate workplace, the social-media censorship of those who question the official line. They are timeless because the desire for absolute power is timeless, and the determination of the powerful to do anything necessary to keep that power is timeless. They are timeless because evil is timeless, and it doesn’t matter where you live, because evil recognizes no borders.

And yet we can’t deny that times have changed. If evil has always been here, it’s also true that over time, evil becomes less and less selective about those on whom its shadow falls. Perhaps the most frustrating aspect is that those who put this evil into motion don’t even bother to hide their footprints anymore. They follow the plan so closely, so predictably, that it’s as if they don’t care that you know what they’re doing. When confronted with the evidence, they simply whisper a few well-chosen words in a few well-chosen ears—conspiracy—as if that’s all that’s needed to discredit you. Meanwhile it’s still sunny where we stand, and anyway, they didn’t say anything on the morning news about clouds, and you can take it to the bank. Right?

Then night falls, and everyone is as quiet as a church mouse. TV

The movie was aired on Thursday, Sept. 17 (not 7), 1970. Interesting & horrifying.

ReplyDeleteRight - fixed. Thanks!

Delete