I'm not quite sure that "Operation Hush" is the best way to describe the process by which quiz shows like The $64,000 Question (Tuesday, 10:00 p.m., CBS) keep their questions secret from the public and the contestants appearing on their programs. After all, when I hear the word "hush," I think of hush money, which is what you pay in order to keep secret something that you'd rather other people not know about. Often, that something happens to be illegal. Do you suppose my years in politics have made me suspicious, cynical, hard-boiled when it comes to things like this? Or is it just that, nearly 70 years later, all of us benefit from hindsight in knowing that most of these shows were rigged?

Frank De Blois describes how the process works on Question, beginning with the questions themselves, which originate with college professor and TV personality Dr. Bergen Evans. They're then passed through for approval by the production team, after which they're sealed in a box which is locked in a vault at Manufacturers Trust bank. On the night of the broadcast, two bank executives, accompanied by a pair of guards, unlock the vault, remove the sealed box, and take a cab to the studio, arriving just before showtime. Once a contestant enters the famed soundproof "isolation booth," all he can hear is host Hal March's voice, and all he can see is March's face.

De Blois relates the efforts made by other programs, ones that offer considerably less than $64,000: I've Got a Secret, Masquerade Party, What's My Line? They're whimsical enough (how do you get someone to refrain from boasting that they're this week's Mystery Guest?), but it's the big-money quiz shows we're interested in. The scandal didn't start with Question, of course; Dotto and Twenty-One were the first programs to be implicated, but eventually, in September 1958, the truth catches up.

According to the always-reliable Wikipedia, "The $64,000 Question was closely monitored by its sponsor's CEO, Revlon's Charles Revson, who often interfered with production, especially attempting to bump contestants he himself disliked, regardless of audience reaction. Revson's brother, Martin, was assigned to oversee production, including heavy discussions of feedback the show received." One of the show's gimmicks, an IBM sorting machine that supposedly selected lower-dollar questions at random, was just a prop; all of the cards, with the questions on them, were identical. Teddy Nadler, one of the show's most famous winners, had been shown some of the questions beforehand, but the producers maintained that he already knew the answers.

One of the things you'll see as we go through this week's issue is the importance that sponsors play in 1950s television. Today, sponsors seldom even choose the programs in which their commercials appear*, but at one time it was the sponsors that created the programs themselves, and even if they simply signed up to pay the freight, so to speak, they insinuated themselves into the program in ways we'd probably find completely unacceptable.

*One reason why sponsor boycotts are often of little practical value is that commercial time purchases are often determined by brokers whose jobs are to fill the available slots. A sponsor withdrawing from a particular show might make the broker's job more difficult, but it doesn't necessarily mean the sponsor endorsed the program in question, nor does it always produce the cause-and-effect that the boycott organizers hope for.

In the case of the quiz show scandals, the desire was to manipulate the winners (whether at the sponsor's whim, as with Question, or to attract larger viewing audiences, as was the motive with other programs). In other instances, sponsors tried to manipulate the content of individual programs. I'll get to that in a tick, if you'll just be a little more patient.

l l l

A couple of weeks ago, we saw the dramatic entry of Walt Disney into the weekly television business, and while Disney may have been the first major studio to take the plunge, they won't be the only one. This week, the focus turns to two of the giants of Hollywood, Warner Brothers and M-G-M, and their entries into the television sweepstakes (both, incidentally, on ABC). The early verdict: while Warner may know how to make movies for theaters, the studio "still has much to learn about producing movies for TV." Meanwhile, M-G-M may have taken "the easiest way out," they also may have produced "the most entertaining show" of all the movie studios this year.

Warner Bros. Presents is a "wheel" series, consisting of three hour-long dramas rotating on an every-third-week schedule. All three are based on, and bear the titles of, past WB movie hits: Kings Row, Casablanca, and Cheyenne. Looking at them in order, Kings Row features Jack Kelly (the role played in the movie by Robert Cummings), Nan Leslie (the movie's Ann Sheridan), and Robert Horton (played memorably by Ronald Reagan), in "soap opera-ish stories" about a young psychiatrist battling the superstitions of the early 1900s; Casablanca, which perhaps has the toughest legacy to live up to, has Charles McGraw as Humphrey Bogart (a thankless task), "who seldom has a chance against heavily written scripts"; and Cheyenne, the most loosely based of the three, which stars Clint Walker as a cowboy who gets into "standard scrapes with bad buys, Indians and cattle rustlers in a rather immature Western."

There's a feeling, expressed elsewhere as well as in this article, that Warner felt all they had to do is show up with their name, and the viewers would follow. Indeed, all three shows are "well-produced and competently acted," and sport both a "lavish budget and technical skill." What they don't have are quality stories; as the review says, "the play's still the thing." That's a lesson that M-G-M seems to take to heart in their offering, M-G-M Parade. Unlike WBP, Parade attempts no new programming, but instead dips into the studio's massive library of hit movies, offering clips and short subjects, along with previews of coming attractions.

|

| George Murphy (L) interviews Robert Taylor |

Warner Bros. eventually gets it right, of course. Cheyenne, the only surviving element of Warner Bros. Presents, runs for seven successful seasons, and the studio becomes an assembly line for PI and Western dramas on ABC. M-G-M, meanwhile, has a more checkered history, but has several hits in co-production with other companies, and has its share of successes. It just goes to show, I guess, that television is your friend.

l l l

No matter where we turn, stories about sponsors keep coming up, and in the New York Teletype, we learn about a recalcitrant sponsor: Pontiac has withdrawn as sponsor of the upcoming Project 20, an occasional series of documentaries which will run on NBC into the 1960s. According to Bob Stahl, speculation is that "the auto company felt it unwise to be associated with the first in the series, 'Nightmare in Red'—even though the show is anti-Communist." The network has another sponsor lined up, and now the episode is scheduled to air sometime in January. Don't worry; the Cold War isn't going anywhere.

Meanwhile, Dan Jenkins reports that the sponsors would like some changes to the format of none other than: M-G-M Parade. Those elements that TV Guide thought made the show successful—clips of old movies and short subjects—apparently aren't as popular with the sponsors, who want "more new film, less old; more attention to commercials, less to picture plugs." Oh well.

Also in the Teletype, Ernie Kovacs has gotten fine reviews for his recent pinch-hitting on Tonight in place of Steve Allen, and the talk is that television's most creative force may get his on show on NBC as a result. He does, eventually; he hosts a summer replacement series for Sid Caesar next summer, after which he becomes the regular Monday-Tuesday host for Tonight, remaining until Allen leaves the program in 1957.

And here's something that sponsors are sure to appreciate: NBC and its affiliates now cover "90 percent of the Nation's TV homes with colorcasts, and are doing so with 10 percent of the network's programming schedule." The motive is to push sales of those RCA color televisions.

l l l

We'll continue with our look at sponsors, but first this message about what's on TV this week. (When's the last time you saw a program interrupt a sponsor?)

Believe it or not, there used to be a time, before it joined the Ivy League, when the University of Pennsylvania used to be a significant player in college football, winning the national championship as recently as 1924. There were even concerns, when television started to affect the sport, that Penn might cut its own TV deal. This, however (and unfortunately for the university), is 1955, not 1924. Nonetheless, the Quakers are on the game of the week this Saturday (1:15 p.m., NBC), although it might be due to their opponent: sixth-ranked Notre Dame. The Fighting Irish rout Penn 46-14, but the news is not all bad: it's the only time this season that Penn scores in double digits, en route to an 0-9 season and a 22-game losing streak.

Sunday sees a genuine television first: the American premiere of the British movie The Constant Husband, the first time that a theatrical movie has ever appeared on American television before being shown in theaters. (Due to the distributor's bankruptcy, the movie hadn't even premiered in London until the past April 21.) The farce stars Rex Harrison as an amnesiac who turns out to be married to six different women. (7:30 p.m., NBC, in color.) In the meantime, while we don't have anyone to match up with Ed Sullivan, that doesn't mean we can't check out his lineup: Liberace, Phil Silvers, opera star Rise Stevens, British singer David Whitfield, and Belgian circus clown Linon. (8:00 p.m., CBS)

Abby Mann, who will win an Oscar in 1961 for writing Judgment at Nuremberg (and later on creates the TV series Kojak) is the author of "The World to Nothing," Monday's Robert Montgomery Presents (9:30 p.m., NBC), the story of a movie star (Eddie Albert) who realizes that his movie success has cost him everything important in his personal life. The night's second prestige anthology, Studio One, opens its eighth season with a tense submarine drama, "Shakedown Cruise," starring Richard Kiley, Lee Marvin, and Martin Brooks. (10:00 p.m., CBS)

The new, more refined Milton Berle Show features a musical revue on Tuesday (8:00 p.m., NBC), directed by and starring Uncle Miltie, with the Will Mastin Trio starring Sammy Davis, Jr., Gloria DeHaven, and Gogi Grant. If you want to see it from the beginning, though, you'll have to pass up the last half hour of this week's Warner Bros. Presents, Casablanca, with guest star Maureen O'Sullivan as a woman whose newspaperman husband was recently released from four years in a Soviet labor camp. (7:30 p.m, ABC)

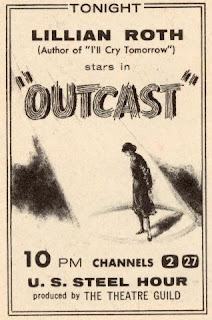

On Wednesday, Lillian Roth makes her television dramatic debut in the U.S. Steel Hour episode "Outcast." (10:00 p.m., CBS). She plays "a once-successful Hollywood writer who is driven to drink by her husband's infidelity and the tragic death of her only child. Her friends try to help her and even get her a chance to resume her career. But she is afraid." Although "Outcast" is based on a story by Frank Gabrielson, the life of Elaine, the character she plays, is remarkably similar to Roth's own life and her battle to come back from alcoholism, which she frankly shared in a memorable appearance on This Is Your Life in 1953, and later detailed in her 1954 autobiography, I'll Cry Tomorrow (turned into a 1955 movie starring Susan Hayward). Roth, one of the first celebrities to publicly discuss struggling with alcoholism, is credited with helping facilitate the public understanding of alcoholism as a disease. As for her performance in "Outcast," the New York Times TV critic Jack Gould calls it "magnificent," and adds that "In its understanding, in its poignancy, in its sensitivity, her performance was one that can only be called memorable."

I mentioned Dr. Bergen Evans in this week's lede, and he hosts the panel show Down You Go* (Thursday, 9:30 p.m., ABC), with panelists Fran Coughlin, Sherl Stern, Patricia Cutts, and John Kiernan, Jr. And your first question might be: who are these people? Well, they were all personalities, having written for or appeared on panel shows in the 1950s. They were probably quick-thinking, witty, conversant, and good conversationalists, essential in the era of live television, and at a time when television has to create its own stars.

*Down You Go, which someone resembles Wheel of Fortune, ran for five seasons, and is one of only six series to appear on all four broadcast networks—ABC, NBC, CBS, and DuMont. The others: The Arthur Murray Party, Pantomime Quiz, Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, The Ernie Kovacs Show, and The Original Amateur Hour.

If you're feeling lost these days, it could be worse: you could be "The Man Without a Country," the classic by Edward Everett Hale, about an American accused of treason who curses the United States during his trial and is sentenced to live the remainder of his life about ship, never to see or hear of his homeland again. Cliff Robertson played Philip Nolan in the 1973 telemovie, but in this week's Matinee Theater colorcast (Friday, 3:00 p.m., NBC), but in today's presentation he's played by Peter Hansen, who as Peter Hanson will star as Lee Baldwin on General Hospital for nearly 30 years.

l l l

Most of you are familiar with the many stories that Rod Serling has told about sponsor interference, but this week's article, "Why Producers Get Gray," will provide you some additional examples that might make you, in Tom Wolfe's words, shake your head like the Fool Killer, "frustrated by the magnitude of the opportunity."

- In Judy Garland’s TV “spectacular,” the New York skyline abruptly underwent a spectacular change. Someone eliminated the familiar Chrysler building, because the show was sponsored by Ford.

- Publicity pictures for CBS’ Crusader series were hastily scrapped. They showed the hero smoking a cigar. The sponsor is a cigaret company.

- When Eartha Kitt sang "C’Est Si Bon" on Ed Sullivan’s show, the lyrics were hastily revised, so that Eartha would yearn for a Lincoln (Ed’s sponsor), instead of a "Cadillac car."

- The CBS daydrama, The Secret Storm, was originally titled "The Storm Within." That title seemed too descriptive of the sponsor's product—Bisodol.

- Two network newscasters ran the same films of a man being lowered to safety from a bridge. CBS’ Doug Edwards pointed out that the man was given a cigar. NBC’s John Cameron Swayze, whose show is sponsored by a cigaret firm, called it "a smoke."

- There was confusion last season over a show’s title. Was it Hey, Mulligan! or The Mickey Rooney Show? The first was widely publicized, until one of the sponsors, Green Giant Peas, recalled a competitor's mulligan stew.

- When Perry Como was ill, Eddie Fisher commented, at the end of one of his Coca-Cola telecasts, "Get well, P.C." His sponsors, constantly vying with Pepsi-Cola, hurriedly advised him never to use those initials again.

I suppose we could just say that they're protecting their turf. Psychiatrists would probably say they're demonstrating a latent insecurity, and prescribe something for them. But first they'd better check to make sure that prescription isn't for a rival pharma company's product. TV

A couple of small points:

ReplyDelete- Your passing mention of Teddy Nadler, who was the biggest winner on the $64,000 shows.

Teddy Nadler was what would come to be called "an idiot savant" (probably not any more these days); he was a not-very-well educated man who had an ability to memorize lists of things, and then repeat them back on demand.

If you've ever seen those old "classic" quiz shows, those were the kinds of questions they asked: list all the facts in the right order, and you won the money - if you happened to have some idea of what you were talking about, so much the better, but the list was enough.

A truly smart man like Charles Van Doren caught on to that angle early on, which is why he sought to get on Twenty-One in the first place; with Teddy Nadler, all that the $64,000 producers had to find out was which lists he'd memorized, and then ask him what he already knew. (It was Teddy Nadler that Jack Barry called " ... a freak with a sponge memory ..." in a TV Guide interview (not by name, but everyone knew who he meant)).

The famous case was Dr. Joyce Brothers, whom Charles Revson hated on sight; he gave the order that Dr. Brothers was to be knocked off $64,000 Question by asking her something that even a professional boxing expert probably wouldn't know.

What Revson didn't know was that Dr. Brothers (who'd been told that the $64,000 producers were looking for was unlikely specialties for contestants) had memorized the Ring Magazine Boxing Encyclopedia (memorization is a skill that medical students learn to cultivate early).

When Hal March asked Dr. Brothers the name of the referee of a certain championship match - after an incredibly detailed listing of arcane facts about the bout - she answered "Tex Rickard!"

Charles Revson was brought up short; Dr. Joyce Brothers went on to a lifetime career in the media; Teddy Nadler lost his job as a letter carrier, and had great difficulty finding employment of any sort for what remained of his life; and if you can find a lesson in any of this, you're welcome to try ...

Back later with more - maybe.

Love it as always!

DeleteAnd then, there was the supposed case of censorship on "Playhouse 90" after it switched from live to tape.

ReplyDeleteThe play was about the Holocaust, and there was a line in it about people being sent to the gas chamber, with that line included on the tape. But with one of the show's sponsors being the American Gas Association, the words "gas chamber" were bleeped out when the show was telecast.