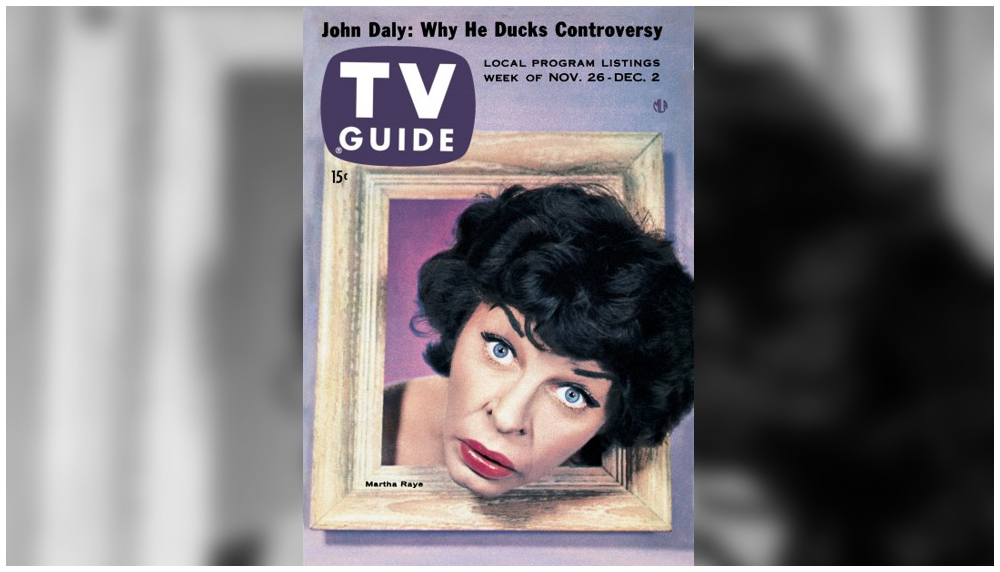

You probably know John Daly best as the charming and urbane host of CBS's What's My Line? on Sunday nights, but this week we get a chance to see him at his day job: vice president in charge of news, public affairs, special events, religion and sports for ABC television and radio, and anchorman of ABC's evening news program.

The combination of the two jobs isn't quite as incongruous as it might seem. "[Goodson-Todman] thought a newsman would have the necessary background to keep an ad lib show going," he says of his Sunday night job. And he enjoys his work as moderator, although he understands that "What's My Line? has got to go sometime. I'm surprised it lasted this long." (It would, in fact, last another twelve years, all with Daly at the helm.) He's really a natural at the job; "Serious and intelligent, he can rarely resist the temptation to be funny." It's what keeps him, he says, from getting ulcers.

|

| Newsman—that's his line. |

And while it's fine for a news show to make "a legitimate comment on any event of public interest," it should be "a conclusion drawn on clearly defined fact." "There should be no subjective declaration of opinion," Daly insists. It's too easy for editorial opinion to drift into subjective opinion, which "could play into the hands of those who might attack the concept of a free press. If we took one stand, they might claim all our news was slanted." I can't help but wonder what he'd think of today's network and cable news divisions.

Daly's weekday schedule runs from 9:00 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. After an hour during which he "plays executive," he works on the script for the evening's news. Lunch is "a business event." At 3:30 p.m. he heads into the newsroom, where he remains until after the show. Then it's on the train and back home. All in all, he reads eight newspapers a day, plus current magazines and biographies. Sundays he spends at home with his family, heading to the studio at 6;00 p.m. for What's My Line?, which airs live at 10:30 p.m. Eastern. With all that, he still gets "eight full hours" of sleep every night. It's another way to prevent ulcers.

John Daly remains at ABC until 1960, when he resigns in protest over the network delaying its election coverage for an hour in order to show Bugs Bunny and The Rifleman. A principled man, he'll also resign as the director of the Voice of America when personnel changes are made without his approval. And to this day, every time I watch him on WML, I say to myself that he's what I want to be when I grow up.

l l l

It was, let's see, about three weeks ago that I last mentioned the trend of movie studios getting into television. Back then, it was Warner Brothers and M-G-M, and before that the focus was on Walt Disney. This week we turn to Fox, whose offering, The 20th Century Fox Hour (Wednesday, 9:00 p.m., CBS) is perhaps the "most ambitious attempt" yet to crash the TV landscape. Unlike the other studios, the Fox Hour "isn't a collection of clips from old films, nor is it a 'showcase' for young, little-known actors." Instead, the studio has chosen to recruit top talent in adaptations of past Fox movie hits.

It's an ambitious proposal indeed, but it faces a not-insignificant challenge: how to adapt a 90-minute or two-hour movie into a 45-minute timeslot. (Especially, I'd think, if viewers have already seen the movie version, and know what you're leaving out.) So far, the results have been mixed: Merle Oberon and Michael Wilding starred in Noel Coward's Cavalcade, but as the review points out, "even the full-length movie version had trouble chronicling a British family from the Boer War [circa 1899] to the 1930s." Next, it was Laura, with George Sanders, Robert Stack, and Dana Wynter; alas, the cast tried "valiantly, but in vain, to evoke the feature film's suspenseful mood." It wasn't until the third outing, The Ox-Bow Incident, that they hit the jackpot, with an outstanding cast including Cameron Mitchell, Raymond Burr, and Robert Wagner; it was "something TV—and Hollywood—could be proud of."

You might have seen episodes from this series on YouTube or in syndication, under the title Hour of Stars. (The most frequently seen DVD episode is "The Miracle on 34th Street," starring Thomas Mitchell as Kris Kringle. Compare and contrast.) It runs for two seasons, continuing to feature big-name stars (though not every week), and by the second season it incorporates original stories as well as movie adaptations. Perhaps that's what the show should have done in the first place, when the story could be tailored to a shorter running time. As anyone familiar with old-time radio knows, it's very difficult to adapt a movie to a finite running time, and the results are not always satisfactory.

There's also a review of another new series that you might be interested in, a Western called Gunsmoke (Saturday, 9:00 p.m., CBS), starring James Arness as Marshal Matt Dillon, and so far the show has produced "taut, action-packed stories." As a frame of reference, Gunsmoke, like Wyatt Earp and Cheyenne, is one of the early "adult" Westerns, in contrast to previous fare by Western heroes like Roy Rogers, Hopalong Cassidy, and Gene Autry, and the storylines reflect it, both in terms of action (in these shows those who get shot often die), and in the moral dilemmas faced by the heroes. Already in this first season, Marshal Dillon "has killed a psychotic gunslinger who had wounded him in an earlier gun battle; he has saved another gunman from being lynched by an angry mob; and he has amputated the leg of a wounded rancher." It is, to be sure, a good day's work.

Arness is excellent in the role, and he's ably backed by a fine supporting cast including Dennis Weaver and Amanda Blake. From the sounds of things, this show might just have a future.

l l l

'Tis the season and all, and if you have any doubt about what's in Santa's bag of toys this year for good little television watchers, look no further than this:

There are more than 20 television programs represented in the picture above, with tie-ins everywhere: everything from a Ramar of the Jungle chemistry set to a Dragnet squad car and game. Even The Today Show gets in the act, with a J. Fred Muggs doll. (So much for those Matt Lauer talking dolls that are gathering dust in some warehouse.) Not surprisingly, Disney is represented by several toys; some things never change. I imagine that if, the next time you're browsing in your local antique store, you run into a Honeymooners bus with Ralph Kramden behind the wheel, or a ukulele endorsed by Jimmy Durante. you'll be shelling out a little more than you would have back in 1955. And if you have one in your attic, better call Antiques Roadshow.

l l l

As for what's on TV this week, what catches my eye?

Saturday's highlight is one of the nation's great sporting traditions, the Army-Navy game, live from Philadelphia, with Lindsey Nelson and Red Grange providing the play-by-play (12:15 p.m, NBC). The usually-mighty Army team has lost three games this season, but they rally this week, defeating #11 Navy 14-6. I notice that one of the Navy players is named Forrestal; any relation? Moving to primetime, it seems that no matter what issue it is from the 1950s, we're running into one of those Max Liebman spectaculars; this time, it's the Rodgers and Hart musical "Dearest Enemy" (8:00 p.m., NBC), with Anne Jeffreys, Robert Sterling, Cyril Ritchard, and Cornelia Otis Skinner. It's a romantic comedy set during the Revolution, but I'm skeptical—none of my enemies are dear to me.

Sunday afternoon on See It Now (4:00 p.m., CBS), the aforementioned Edward R. Murrow hosts a 90-minute documentary on "The Nation's Schools" and the challenges they face, including aging school facilities, federal aid to education, and the lack of good teachers. Let's see, that was nearly 70 years ago, and it seems like the same problems still exist. On a lighter note, Ed Sullivan's guests tonight (7:00 p.m., CBS) are Pearl Bailey, who recently completed a role in Bob Hope's film That Certain Feeling (and that's Bob at left, in an ad for RCA, plugging that very movie); comedian Dick Shawn; the Goofers, comedy vocal and instrumental group; the Princeton Triangle Club; Collier's magazine's All-America football team; and opera star Licia Albanese and her three-year old son doing a scene from Madama Butterfly. Afterwards, catch WCCO's movie The Stranger (9:30 p.m.), a sinister noir with Edward G. Robinson investigating a Nazi spy (Orson Welles).

I'm not positive, but I think Monday's presentation on Studio One (9:00 p.m., CBS) relates to a part of pop culture history that would have been assumed knowledge back in 1955. The episode is "The Man Who Caught the Ball at Coogan's Bluff," by Rod Serling, starring Alan Young and Gisele MacKenzie, and the storyline is thus: "George was a shy and unsung government worker when he entered the ball park. But after making that spectacular bleachers catch of a home-run ball, he was a national hero, and sky no longer." I haven't seen the episode and couldn't find a whole lot out about it other than what you read here, but there are a few assumptions we can make. Coogan's Bluff was the location of, and the nickname for, the Polo Grounds; the most famous home run ever hit there was probably Bobby Thomson's "The Giants win the pennant!" blast in the 1951 playoff against the Brooklyn Dodgers. Even non-baseball fans were familiar with it; if this story doesn't actually use that game as the background, the viewers would have supplied the details.

On Tuesday's Warner Brothers Presents edition of "Casablanca" (6:30 p.m., ABC), "A dealer in antiques and a professor are both interested in acquiring a priceless page from an ancient Bible. But Rick wants money to provide education for the ragged Arab shoeshine boy who gave him the valuable parchment." Does this sound like the Rick we know and love from Humphrey Bogart's portrayal? I suppose, if you're a cynic with a heart of gold. Personally, it sounds more to me like a case for Indiana Jones. Later, on The Red Skelton Show (Tuesday, 8:30 p.m., CBS), Red and guest star Peter Lorre appear in a sketch called "Phantom of the Ballet." "Skelton, as a private detective with a mail-order-school diploma, tries to track down a maniacal killer (Lorre). The murderer as a penchant for assassinating members of a ballet troupe." OK, you've got me on that one.

Wednesday is the second big sporting event of the week, the world welterweight boxing championship from Boston, with champion Carmen Basilio taking on the #1 challenger, former champ Tony DeMarco (9:00 p.m., ABC). Basilio defends his title with a 12th round knockout in what will be voted the fight of the year; you can see it all here. Thursday's highlight, if you can call it that, comes on Tonight (11:00 p.m., NBC), when a dentist comes on the show to drill Steve's teeth. There's also a modern dance interpretation by Katherine Litz; whether or not she's actually doing an interpretation of Steve's dental work is anyone's guess. And Friday gives us some good, old-fashioned murder: a bank embezzler is suspected of it in International Playhouse (8:30 p.m., KEYC), a young man plots it against his lover's husband in The Vise (8:30 p.m., ABC), and the men of The Lineup investigate it when an ad executive is found dead (9:00 p.m., CBS).

l l l

This week's words of wisdom come from George Burns, via the As We See It editorial. Burns has a new autobiography out, I Love Her, That's Why!; it's mostly anecdotical, talking about Gracie and their friends, but near the end of the book he turns serious for a moment. He and Gracie have moved into television, and he discusses his philosophy of playing to the audience.

If we are successful, it is because we don't play down to an audience—we don't believe in that. There has been foolish talk about audiences having an average 12-year-old mind; it just isn't true. They are older than anybody, and wiser. And what is more, every individual among them is a manager, because in this day of television, he owns his own theater. The first thing an actor learns is to get along with the manager. He does well when he doesn't forget it.

Now, I don't know if that was ever really true, in television or in any other form of entertainment, but already, as we come to the end of 1955, it is becoming an issue for Merrill Panitt and the editors. "We would like to see that paragraph engraved on the forehead of every network official, advertising executive, producer, director, writer and performer who has anything to do with television," he writes. "Whatever real progress television has made has come from men who realize that the only 12-year-old thinking in America is done by 12-year-olds; that the surest way to lose an audience is to talk down to it."

As I said, this may never have been the case, but it certainly isn't the case today. In just about every way, today's maestros, people not only are being pandered to, we're practically demanding it. Whether it's the entertainment industry or the political establishment, the lowest common denominator rules; the simpler the answer, the better. We don't want to be stimulated; we don't want to face anything difficult. This isn't to suggest that there aren't intelligent forms of entertainment today, television programs that challenge not only the intellect but the conscience. They are, however, the exception rather than the rule.

The editorial concludes by suggesting that the television audience "will turn away from a program that does not respect its intelligence," but I fear that's a pipe dream nowadays. We've been dumbed down in every way, from the cradle to the grave and everything in-between, and we seem to like it just fine. In a world dominated by memes, simplistic thinking, and short attention spans, we are all 12-year-olds now. TV