How many times has this happened to you: you're driving through a strange town when your car breaks down. While you're waiting for repairs, you have a run-in with one of the local punks, who just happens to be the son of one of the most important men in town. Later on, the punk turns up dead, and guess who the prime suspect is? You!

I don't know about you, but that's never happened to me. I won't say that it won't ever happen, because that seems to be just the kind of person to whom it does happen. At least that's the cliche that's on display in this week's episode of Run for Your Life (Monday, 9:00 p.m. CT, NBC), starring Ben Gazzara as the doomed Paul Bryan, a man with only a few months (years?) to live.* We know Paul didn't do it, because he's the show's star; and we know he won't be convicted, because the show's called Run For Your Life and not You're Sentenced to Life. So why even bother with a storyline like this? Perhaps because it gives you a heavy you can really hate, or a heavy who reforms once he discovers the true meaning of life, or because it gives West Coast writers a chance to ridicule small-minded small-town America. Your guess is as good as mine. But with absolutely no prior knowledge of what I'm going to find, let's take a look through the listings and see if we can find any other TV cliches—or tropes, as they've come to be known—on the small screen this week.

*That hasn't happened to most of us either, I'll wager. At least not more than once.

Here's one, on Daniel Boone (Thursday, 6:30 p.m., NBC): "Daniel, the fort's best runner, sprains an ankle, which spells bad news for the settlers who have bet on him to win the hotly contested annual foot race with the Indians." Yes: whenever I get sick or come down with some debilitating ailment, I always check the calendar, because I know something important is about to happen. Don't ask me how, I just know it. Did you ever notice how you never see a listing like "Daniel sprains an ankle, and is grateful he doesn't have anything planned for the week"? Of course not; that doesn't make for very interesting television. You'd have to add the sentence "And then one thing after another seems to pop up" just to get a script out of it.

There's a rerun of Lee Marvin's M Squad (Wednesday, 12:15 a.m., KSTP) that has another typical police story: "An ex-convict, suspected of murder, is about to commit suicide by leaping from a high window. Ballinger races to get enough evidence to clear the man before he jumps to his death." Will Ballinger get the evidence, and will it be in time? What do you think? "A man suspected of murder threatens suicide. Ballinger looks into the case, but discovers the man really is guilty, and his death wouldn't change a thing." Have you seen that lately?

The Big Valley (Wednesday, 8:00 p.m., ABC) offers a slight variation on the episode from Run For Your Life: "Gil Anders comes to the Barkley ranch looking for Heath and is shot from ambush by two bounty hunters, who claim he's wanted for murder." This will, of course, come as a complete surprise to Gil, who has no idea why anyone would suspect him of murder. Whether or not you think he's guilty of the crime depends on whether or not you think Barbara Stanwyck would let her son hang around with cold-blooded killers. Heath's a lawyer, anyway, so he'll be sure to get Gil off.

In Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (Sunday, 6:00 p.m., ABC), the Seaview takes on a couple of men adrift in a lifeboat, "unaware the they're rescued a pair of escaped convicts." Because people are never what they seem to be. Look for a scene where the radio operator gets a message about two convicts on the run, and the crew gradually put two and two together. One of the escapees is Nehemiah Persoff►, which means you get two tropes for the price of one since Persoff is never who or what he appears to be either, and if you ever run into him on a dark street you're right to feel uneasy.

Petticoat Junction (Saturday, 8:30 p.m., CBS) has a storyline that's typical of what happens when misunderstandings occur: "A feud between Charley and Floyd has sidetracked the Cannonball and paralyzed Hooterville Valley." If you doubt the likelihood that the two train engineers will get their feud patched up by the end of the thirty minutes, you also probably think next week the train will be piloted by Arnold Ziffel. Besides, it just wouldn't be as romantic if the service was being run by Amtrak.

On The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (Saturday, 6:30 p.m., ABC): "Harriet has been receiving a daily rose from a secret admirer." Will this be the end of the Nelson's marriage? Will we see Ozzie next week on Divorce Court, or perhaps it will be Perry Mason defending "The Case of the Cantankerous Crooner"? I'll bet there's a logical explanation for the whole thing, something that will be discovered in just under thirty minutes that will leave Ozzie feeling foolish, Harriet secretly pleased that Ozzie can still get jealous, and the whole family having a good laugh.

I could go on, but you get the point. There are only a handful of original stories in existence; most people use the number seven, but that could be a cliche in and of itself. And while some of them are commonplace, things that could happen to any of us, too many of them are like the one that Paul Bryan faces in Run for Your Life: ones that we scoff at for being so utterly absurd, and that keep us tuning in each week.

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup..

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup..

Sullivan: Scheduled guests: singer Jerry Vale; Metropolitan Opera soprano Birgit Nilsson; comics London Lee and Nancy Walker; the singing Swinging Lads; the comedy team of Stiller and Meara; ballerina Joyce Cuoco; the Arirang Ballet, Korean dance and instrumental group; the Yong Brothers, balancing act; and the Berosini Chimps..

Palace: Host Ray Bolger presents singer Kay Starr; jazz vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, accompanied by 7-year-old drummer Jim Bradley; impressionist Rich Little; comedian Norm Crosby; escape artist Michael De La Vega; and the Five Amandis, teeterboard act.

This surely must rank as an outstanding week for each show. Ed has one of the greatest opera singers ever in Birgit Nilsson, one of the most pleasant voices of the 1960s in Jerry Vale, and one of the most lasting of husband-and-wife comedy teams, Stiller and Meara. The Palace counters with one of the great song-and-dance men in Ray Bolger, the legendary Lionel Hampton, and the great jazz and pop singer Kay Starr, plus Norm Crosby and Rich Little. Perhaps those two make the crucial difference, and put The Palace over the line by a nose.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

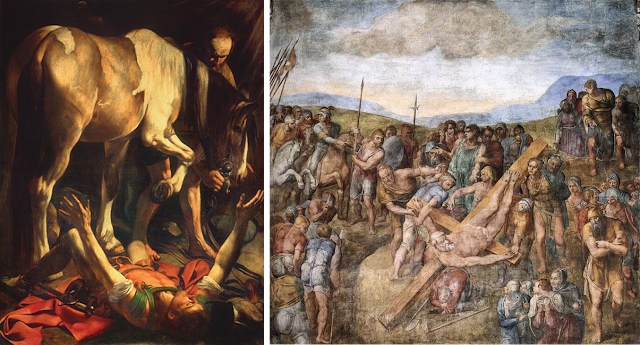

A program that might represent some of the best that television has to offer is Cappella Paolina (Sunday, 9:00 a.m., CBS). Cappella Paolina is the Vatican's Pauline Chapel, and for the first time in history, television cameras are being allowed inside the chapel to take a closer look at two of Michelangelo's least-known frescoes: "The Conversion of St. Paul" and "The Crucifixion of St. Peter." It's too bad this program wasn't broadcast in color, because I'd imagine that the beauties and subtleties of Michelangelo's work are most appreciated that way. (To see if I'm right, check out a more recent documentary here.) It's also too bad that WCCO, the CBS affiliate in Minneapolis, didn't consider this program worth airing, but then they were committed to Business and Finance and Religious News. When I was growing up, I doubt I ever knew Lamp unto My Feet and Look Up and Live even existed.

Here's one, on Daniel Boone (Thursday, 6:30 p.m., NBC): "Daniel, the fort's best runner, sprains an ankle, which spells bad news for the settlers who have bet on him to win the hotly contested annual foot race with the Indians." Yes: whenever I get sick or come down with some debilitating ailment, I always check the calendar, because I know something important is about to happen. Don't ask me how, I just know it. Did you ever notice how you never see a listing like "Daniel sprains an ankle, and is grateful he doesn't have anything planned for the week"? Of course not; that doesn't make for very interesting television. You'd have to add the sentence "And then one thing after another seems to pop up" just to get a script out of it.

There's a rerun of Lee Marvin's M Squad (Wednesday, 12:15 a.m., KSTP) that has another typical police story: "An ex-convict, suspected of murder, is about to commit suicide by leaping from a high window. Ballinger races to get enough evidence to clear the man before he jumps to his death." Will Ballinger get the evidence, and will it be in time? What do you think? "A man suspected of murder threatens suicide. Ballinger looks into the case, but discovers the man really is guilty, and his death wouldn't change a thing." Have you seen that lately?

The Big Valley (Wednesday, 8:00 p.m., ABC) offers a slight variation on the episode from Run For Your Life: "Gil Anders comes to the Barkley ranch looking for Heath and is shot from ambush by two bounty hunters, who claim he's wanted for murder." This will, of course, come as a complete surprise to Gil, who has no idea why anyone would suspect him of murder. Whether or not you think he's guilty of the crime depends on whether or not you think Barbara Stanwyck would let her son hang around with cold-blooded killers. Heath's a lawyer, anyway, so he'll be sure to get Gil off.

Petticoat Junction (Saturday, 8:30 p.m., CBS) has a storyline that's typical of what happens when misunderstandings occur: "A feud between Charley and Floyd has sidetracked the Cannonball and paralyzed Hooterville Valley." If you doubt the likelihood that the two train engineers will get their feud patched up by the end of the thirty minutes, you also probably think next week the train will be piloted by Arnold Ziffel. Besides, it just wouldn't be as romantic if the service was being run by Amtrak.

On The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (Saturday, 6:30 p.m., ABC): "Harriet has been receiving a daily rose from a secret admirer." Will this be the end of the Nelson's marriage? Will we see Ozzie next week on Divorce Court, or perhaps it will be Perry Mason defending "The Case of the Cantankerous Crooner"? I'll bet there's a logical explanation for the whole thing, something that will be discovered in just under thirty minutes that will leave Ozzie feeling foolish, Harriet secretly pleased that Ozzie can still get jealous, and the whole family having a good laugh.

I could go on, but you get the point. There are only a handful of original stories in existence; most people use the number seven, but that could be a cliche in and of itself. And while some of them are commonplace, things that could happen to any of us, too many of them are like the one that Paul Bryan faces in Run for Your Life: ones that we scoff at for being so utterly absurd, and that keep us tuning in each week.

l l l

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup..

During the 60s, the Ed Sullivan Show and The Hollywood Palace were the premiere variety shows on television. Whenever they appear in TV Guide together, we'll match them up and see who has the best lineup..Sullivan: Scheduled guests: singer Jerry Vale; Metropolitan Opera soprano Birgit Nilsson; comics London Lee and Nancy Walker; the singing Swinging Lads; the comedy team of Stiller and Meara; ballerina Joyce Cuoco; the Arirang Ballet, Korean dance and instrumental group; the Yong Brothers, balancing act; and the Berosini Chimps..

Palace: Host Ray Bolger presents singer Kay Starr; jazz vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, accompanied by 7-year-old drummer Jim Bradley; impressionist Rich Little; comedian Norm Crosby; escape artist Michael De La Vega; and the Five Amandis, teeterboard act.

This surely must rank as an outstanding week for each show. Ed has one of the greatest opera singers ever in Birgit Nilsson, one of the most pleasant voices of the 1960s in Jerry Vale, and one of the most lasting of husband-and-wife comedy teams, Stiller and Meara. The Palace counters with one of the great song-and-dance men in Ray Bolger, the legendary Lionel Hampton, and the great jazz and pop singer Kay Starr, plus Norm Crosby and Rich Little. Perhaps those two make the crucial difference, and put The Palace over the line by a nose.

l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era. This week, it's the readers' turn to tell Cleveland Amory what they think, with the annual season-ending Letters column. As in: "I think it's a shame that you have someone like Cleveland Amory to review T.V. stories. This man hardly has anything nice to say ever. Everyone has their own taste. But this man has no taste what so ever. . . Please tell me one thing, does this man like anything? There are no two ways about it. Mr. Amory is for the birds."

That was from Helen Rubino of Union City, New Jersey, who doesn't think Cleve likes anything. But James R. Hilt, of Milford, Connecticut, complains that "he gives a good review for an idiotic show such as Batman." Considering that I own the Blu-Ray version of Batman, I think I'm offended by that one. I feel comforted by Cynthia Neel of Villanova, Pennsylvania, who says that "It's a pleasure to see that Cleveland Amory is one of the few people who recognizes a good show." That's not to say she was talking about Batman, but still.

A "very dissatisfied ex-reader" says Amory has "a lot of nerve" to knock The Legend of Jesse James, "the best program on television, and Chris Jones is the best thing to come along since summer vacation! My grandmother used to say Jesse James had some good points to him. He wasn't all bad. She should know, she let him hide in her barn." That last fact, frankly, is more interesting than the letter, but Jesse James ran for 34 episodes in 1965-66, ending just a month before this issue. As for the real Jesse James having some good points, I suppose everyone does. Hitler liked dogs. And, like Jesse James, he was also a narcistic, psychopathic killer.

Mrs. R.A. of Manchester, Massachusetts says the best thing on TV is the news. M.G.P. of Louisville, Kentucky, says the worst thing on TV is the news. "A TV Guide reader" says that "Johnny Carson is great. Why doesn't Mr. Amory say so?" "Disgusted" replies that Johnny Carson "must think that the public patience with his repertory group is as limitless as they limited, and "can see no reason for his having the same people saying so little on so much."

The last word goes to C.A., of The Moon, who simply says, "See, you can't win 'em all. See you next fall."

l l l

A program that might represent some of the best that television has to offer is Cappella Paolina (Sunday, 9:00 a.m., CBS). Cappella Paolina is the Vatican's Pauline Chapel, and for the first time in history, television cameras are being allowed inside the chapel to take a closer look at two of Michelangelo's least-known frescoes: "The Conversion of St. Paul" and "The Crucifixion of St. Peter." It's too bad this program wasn't broadcast in color, because I'd imagine that the beauties and subtleties of Michelangelo's work are most appreciated that way. (To see if I'm right, check out a more recent documentary here.) It's also too bad that WCCO, the CBS affiliate in Minneapolis, didn't consider this program worth airing, but then they were committed to Business and Finance and Religious News. When I was growing up, I doubt I ever knew Lamp unto My Feet and Look Up and Live even existed.

|

| "The Conversion of St. Paul" (left), "The Crucifixion of St. Peter." Interstingly enough, the TV Guide Close-Up shows "The Last Judgment,' which is located in the Sistine Chapel. |

l l l

So Henry Steele Commager says television must reform itself or else. To which you might ask, "or else what?", and who the hell is Henry Steele Commager anyway?

To answer the second question first, Commager was a noted historian, a champion of the Enlightenment, and a chronicler of modern liberalism. Insofar as Commager defined what liberalism was, he could be seen as a liberal version of William F. Buckley, Jr.* Commager's article is the fifth in TV Guide's ongoing series "assessing the effects of television on our society," which is a lot like the mission of this here blog.

*Who once wrote a letter to Commager asking if he had changed his middle name to "Steele" in admiration of Josef Stalin, the "Man of Steel." It's that kind of cheekiness that I always admired in WFB.

Commager acknowledges the importance of television, calling it "the most important invention in the history of the communication of knowledge" since the inventions of the University and the printing press. He believes it foolish to think that, as some people put it, the only changes left for television are technical ones, such as color vs. black and white; it is a young medium, he says, continuing to evolve, which means that this look at TV should be regarded as "an interim judgment." And part of the problem that television faces is that, in its 25 years, it hasn't quite figured out what it should be.

Arguably it should be a medium devoted to serving the public interest, as is set out in the FCC act of 1934. And, as Commager points out, there are enough money-making enterprises out there that television shouldn't have to be one of them; "all the important contributions are to be made to the commonwealth, not the private wealth." The rub, so to speak, is that television as an industry is controlled by "men without vision or imagination in anything other than their major interests - manufacturing, marketing and finance." Yes, and it's probably also true that only men with those kinds of interests would have had the wherewithal to create the mighty networks that exist in 1966. Based on this assessment, it would seem as if the question Commager asks—is TV a form of entertainment and information, or is it a form of education similar to the University and the Foundation—has a self-ordained answer. Yes, he concedes, it can be both, but "who can doubt that the proportions are badly mixed?" And while the men who run television boast of their independence from government control, they say very little about "independence where it really counts"—freedom from the advertisers who "determine policy and content."

So we're faced with an argument that we've read and heard many times—it is the drive for profit, and the resulting lowest-common-denominator programming that results—that is responsible for the quality (or lack thereof) of television. Television, Commager laments, has failed utterly in the realm of education: "it neither transmits the knowledge of the past to the next generation, nor contributes to professional training, nor does it expand the boundaries of knowledge." It has no professional standards and practices. What "meager" contributions it has made in these areas has been more than offset by "its contributions to noneducation and to the narrowing of intellectual horizons."

As it happens, I can agree with Commager on much of this. But the question remains: what is one to do about it? We've created a public broadcasting station that is supposed to be independent of pressures created by ratings and advertising dollars, but in its effort to solicit direct financial contributions from viewers, which would be the purest way of judging a network's ability to connect with the public, it is forced to rely on the basest form of crowd-pleasing shows, with virtually no attention to the educational and cultural forces which we were assured would result from its creation.

Commager's answer to this, not surprisingly given his ideological bent, is government control, specifically an empowering of the FCC. Were television to be treated like any other utility, it would have to constantly show the ways in which it serves the public interest, lest it lose its license. An FCC reconstituted in this manner would have "authority to make findings and impose decisions with respect to such matters as content and advertising, and to refuse to license stations which fail to devote themselves to the public interest." Again, the problem with this is that Commager fails to appreciate that at least a part of the "public interest" consists of what the public is interested in. With this attitude, television soon becomes a kind of medicine that people dread taking, even though they're being told that it's good for them. And by allowing a commission—one with political appointments, no doubt, and how could anything possibly go wrong with that?—rather than the public to choose what should be broadcast, how does one truly find out the pulse of the viewers?

This much is clear: Commager is leery at best, and opposed and worst, to the idea of private ownership of television broadcasting. It may be the norm here, he states, but not in the rest of the world. Which, one would suppose, is why there's such a call for American television programs in the rest of the world, right? Or why the shows imported from Britain so closely resemble ones being shown here. Henry Steele Commager is not a stupid man, but he's something like a lumbering ox, an easy target. He makes some very good points about the problems and challenges of television, but like so many, fails to come up with many answers. I can't really fault him for that, either, though; after all, you don't see many coming from me, do you?

On the other hand, For the Record gives us a speech by Edwin Bayley, VP of National Educational Television (NET), who says that money for educational television should come neither from federal nor state government. Once you get government involved in funding, Bayley says, "the inclination is to dictate program content." He cites various civil rights programs that were rejected by educational television stations in the South due to worries "they would offend state legislatures that had provided them with funds." The preferred source for funding, according to Bayley, is "foundations, industry and business."

Not much to see in the Teletype sections this week, other than a note that "ABC's daytime show Confidential for Women goes off the air July 8. It'll be replaced by The Newlywed Game." We all know how that turned out. CBS has a new Peanuts cartoon planned for around Halloween, and hopes that It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown will have some of the success of A Charlie Brown Christmas.

The fortunes of dramatic programming ebb and flow in TV Guide, depending on what year you read. This year it's a bull market for drama, with ABC talking about a monthly Sunday Night at the Theatre in addition to Stage 67. NBC is producing a version of "Othello," while CBS, basking in the glow from their critically acclaimed production of "Death of a Salesman," looks to duplicate the results with "The Crucible" and "The Glass Menagerie," which wind up airing on CBS Playhouse. Just wait a year or two, and the tide will turn again.

To answer the second question first, Commager was a noted historian, a champion of the Enlightenment, and a chronicler of modern liberalism. Insofar as Commager defined what liberalism was, he could be seen as a liberal version of William F. Buckley, Jr.* Commager's article is the fifth in TV Guide's ongoing series "assessing the effects of television on our society," which is a lot like the mission of this here blog.

*Who once wrote a letter to Commager asking if he had changed his middle name to "Steele" in admiration of Josef Stalin, the "Man of Steel." It's that kind of cheekiness that I always admired in WFB.

Commager acknowledges the importance of television, calling it "the most important invention in the history of the communication of knowledge" since the inventions of the University and the printing press. He believes it foolish to think that, as some people put it, the only changes left for television are technical ones, such as color vs. black and white; it is a young medium, he says, continuing to evolve, which means that this look at TV should be regarded as "an interim judgment." And part of the problem that television faces is that, in its 25 years, it hasn't quite figured out what it should be.

|

| Commager from an early '50s TV interview |

So we're faced with an argument that we've read and heard many times—it is the drive for profit, and the resulting lowest-common-denominator programming that results—that is responsible for the quality (or lack thereof) of television. Television, Commager laments, has failed utterly in the realm of education: "it neither transmits the knowledge of the past to the next generation, nor contributes to professional training, nor does it expand the boundaries of knowledge." It has no professional standards and practices. What "meager" contributions it has made in these areas has been more than offset by "its contributions to noneducation and to the narrowing of intellectual horizons."

As it happens, I can agree with Commager on much of this. But the question remains: what is one to do about it? We've created a public broadcasting station that is supposed to be independent of pressures created by ratings and advertising dollars, but in its effort to solicit direct financial contributions from viewers, which would be the purest way of judging a network's ability to connect with the public, it is forced to rely on the basest form of crowd-pleasing shows, with virtually no attention to the educational and cultural forces which we were assured would result from its creation.

Commager's answer to this, not surprisingly given his ideological bent, is government control, specifically an empowering of the FCC. Were television to be treated like any other utility, it would have to constantly show the ways in which it serves the public interest, lest it lose its license. An FCC reconstituted in this manner would have "authority to make findings and impose decisions with respect to such matters as content and advertising, and to refuse to license stations which fail to devote themselves to the public interest." Again, the problem with this is that Commager fails to appreciate that at least a part of the "public interest" consists of what the public is interested in. With this attitude, television soon becomes a kind of medicine that people dread taking, even though they're being told that it's good for them. And by allowing a commission—one with political appointments, no doubt, and how could anything possibly go wrong with that?—rather than the public to choose what should be broadcast, how does one truly find out the pulse of the viewers?

This much is clear: Commager is leery at best, and opposed and worst, to the idea of private ownership of television broadcasting. It may be the norm here, he states, but not in the rest of the world. Which, one would suppose, is why there's such a call for American television programs in the rest of the world, right? Or why the shows imported from Britain so closely resemble ones being shown here. Henry Steele Commager is not a stupid man, but he's something like a lumbering ox, an easy target. He makes some very good points about the problems and challenges of television, but like so many, fails to come up with many answers. I can't really fault him for that, either, though; after all, you don't see many coming from me, do you?

l l l

On the other hand, For the Record gives us a speech by Edwin Bayley, VP of National Educational Television (NET), who says that money for educational television should come neither from federal nor state government. Once you get government involved in funding, Bayley says, "the inclination is to dictate program content." He cites various civil rights programs that were rejected by educational television stations in the South due to worries "they would offend state legislatures that had provided them with funds." The preferred source for funding, according to Bayley, is "foundations, industry and business."

Not much to see in the Teletype sections this week, other than a note that "ABC's daytime show Confidential for Women goes off the air July 8. It'll be replaced by The Newlywed Game." We all know how that turned out. CBS has a new Peanuts cartoon planned for around Halloween, and hopes that It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown will have some of the success of A Charlie Brown Christmas.

The fortunes of dramatic programming ebb and flow in TV Guide, depending on what year you read. This year it's a bull market for drama, with ABC talking about a monthly Sunday Night at the Theatre in addition to Stage 67. NBC is producing a version of "Othello," while CBS, basking in the glow from their critically acclaimed production of "Death of a Salesman," looks to duplicate the results with "The Crucible" and "The Glass Menagerie," which wind up airing on CBS Playhouse. Just wait a year or two, and the tide will turn again.

"Unlike the U.S. House and Senate," the British House of Lords is considering bringing television cameras in to the chamber. They've agreed to a trial run, over the objections of Lord Balfour, who memorably observed that televising the Lords (which would invariably lead to cameras in the House of Commons as well) might cause viewers to look at the House "rather as a zoo, and frankly I do not think the public would like all the exhibits." As he said this, notes TV Guide, "at least two members were asleep, and several front-benchers were hunched down in their seats, their feet wedged against the tables opposite them." Good thing that would never happen in this country. TV

No comments

Post a Comment

Thanks for writing! Drive safely!