Take, for instance, Sunday's episode of CBS Playhouse, the network's successor to the fabled Playhouse 90*. Set in 1963, "The Final War of Olly Winters" stars Ivan Dixon as an Army sergeant serving as a United States military adviser in South Vietnam at a time before American soldiers had been committed to combat.

*Unlike the original, CBS Playhouse aired on an occasional basis (only twelve were shown over the three years that the show ran; it was dropped for lack of sponsorship).

What I was really thinking about, though, was the casting of Ivan Dixon as Winter. Dixon was far from being unknown (he'd appeared in many movies and television shows, including a memorable appearance on The Twilight Zone in "The Big Tall Wish." At this point, however, he's been on Hogan's Heroes for nearly two full seasons, playing Staff Sergeant Kinchloe; Olly Winter is also a staff sergeant. Same rank, same uniform, same mustache. Surely viewers (and there were 30 million of them) would have been alerted by the TV Guide description that they were going to see something far different from Hogan. Still, look at him in that picture. Consider that he's been a soldier for 20 years—since 1943. Sure, Kinch would have been promoted for his heroic service in Stalag 13, but in some way you might have thought of Winter as Kinch, but in a very, very different story. I don't want to make too fine a point there, but you have to admit that it's kind of unnerving to see an actor playing a role that, on the exterior, looks so similar to the role in which we know and love him. And don't forget that he's playing Kinch at the time; as a matter of fact, you could have seen him on Hogan's Heroes just 48 hours earlier, Friday night at 8:30 p.m.

A couple of points about this: first, it's a neat trick to set the story in 1963, before Vietnam had become so polarizing. By the late 1960s, war protestors were vilifying American soldiers as war criminals, baby murderers, and the like. By doing this, I wonder if Ronald Ribman, the author of the play, wasn't trying to create some distance in order to make it easier for Winters to be accepted as a protagonist by the audience. I'm not attempting to psychoanalyze Ribman or his motives, but it does seem logical that making it a period piece by only four years would make sense.

What I was really thinking about, though, was the casting of Ivan Dixon as Winter. Dixon was far from being unknown (he'd appeared in many movies and television shows, including a memorable appearance on The Twilight Zone in "The Big Tall Wish." At this point, however, he's been on Hogan's Heroes for nearly two full seasons, playing Staff Sergeant Kinchloe; Olly Winter is also a staff sergeant. Same rank, same uniform, same mustache. Surely viewers (and there were 30 million of them) would have been alerted by the TV Guide description that they were going to see something far different from Hogan. Still, look at him in that picture. Consider that he's been a soldier for 20 years—since 1943. Sure, Kinch would have been promoted for his heroic service in Stalag 13, but in some way you might have thought of Winter as Kinch, but in a very, very different story. I don't want to make too fine a point there, but you have to admit that it's kind of unnerving to see an actor playing a role that, on the exterior, looks so similar to the role in which we know and love him. And don't forget that he's playing Kinch at the time; as a matter of fact, you could have seen him on Hogan's Heroes just 48 hours earlier, Friday night at 8:30 p.m.

In addition to Dixon, who will be nominated for an Emmy for Best Actor for his brilliant performance, "Olly Winter" boasts top credentials; Paul Bogart, the director, had already won an Emmy for The Defenders and he'll get a nomination for Best Director for this as well. (He was also nominated for directing sitcoms like All in the Family and The Golden Girls; hell, he could have directed an episode of Hogan's Heroes!) Fred Coe, the producer, had also done Playhouse 90. And the music was by Aaron Copland. "The Final War of Olly Winter" is a critical as well as popular success; I wish this had led to even more dramas of this type.

CBS would make one final effort in the early 1970s to bring back the dramatic anthology concept, this time resurrecting the Playhouse 90 title in its entirety (as well as the opening music and graphics); CBS Playhouse 90 would air a number of quality plays, including Ingmar Bergman's "The Lie" and Brian Moore's "Catholics." "The Final War of Olly Winter" isn't available commercially or online, but it can be seen at the Paley Center in New York or the UCLA Film & Television Archive in L.A. It's probably the thousandth show I have on my list to watch at places I'll likely never get to.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

As is typical when ratings are involved, there was good news for everyone. According to the Arbitron overnight figures, CBS scored a "smashing" victory, drawing 59 percent of the football audience and besting NBC by more than seven points; NBC countered with Nielsen figures that showed them trailing CBS by only 1.2 points in the critical New York City market. (The final ratings: CBS won the Nielsens 22.6 to 18.5, and the market share 43-36.)

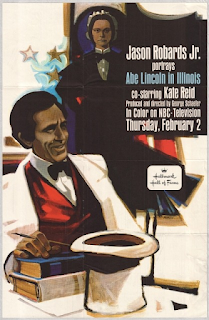

Thursday begins with yet another quality drama on the Hallmark Hall of Fame: "Abe Lincoln in Illinois" (9:30 p.m., NBC), a 1964 rerun starring Jason Robards as Honest Abe, with Kate Reid as Mary Todd. Robert Sherwood's Pulitzer winning play begins in 1830 with young Lincoln establishing his law practice, and ends in 1860 with him bidding farewell as he departs by train for Washington, D.C., to be sworn in as President of the United States. Thursday ends with "David Frost's Night Out in London" on the aforementioned ABC Stage 67 (10:00 p.m.), with David "heading where the action is" in "the most 'In' town in the world," and running into Sir Laurence Olivier, Albert Finney, and Peter Sellers.

l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era. When you think of The Jackie Gleason Show, what comes to your mind first? Is it The Honeymooners, the classic sitcom? Is it the 1950s variety show, on which the Honeymooners sketches first appeared? Is it The American Scene Magazine, Gleason's 1962 return to weekly television? Or is it the show that Cleveland Amory reviews this week, which originates from "The Sun and Fun Capital of the World," Miami Beach and brings The Honeymooners back as a regular feature? If you're like me (and, once again, I hope you aren't), this is the version you're most familiar with. And it's a good thing, Cleve says, because this show, which has for too long been too average, is now "not only as bright comedy as is available anywhere on your dial, but it is also, at its best each week, a full-scale musical comedy."

Key to the show's evolution has been the reunion of Gleason with his Honeymooners on a regular basis—not just the great Art Carney, who makes The Great One "a great deal Greater," but the additions of Sheila MacRae as Alice (who, in her first continuing TV role, shows herself "not only a fine actress but a terrific reactress") and Jane Kean as Trixie ("both singer and swinger"), to make what Amory calls "a winsome foresome and then some." The idea of making The Honeymooners into a musical comedy (which, I'll admit, would not have occurred to me) has been transformational; the songs by Lyn Duddy and Jerry Bresler "are, if not Broadway caliber, so close to it that, when you consider they are turning them out week after week, even more remarkable than Broadway."

The show isn't perfect; Amory finds that the characters of Ralph and Norton are still "unnecessarily crude," a critique that many will agree with today; and, he says, "too many of the routines are routine," although my personal opinion always was that by (for example) sending the Kramdens and Nortons on adventures around the world, they were straying too far from the skit's original concept. But I suppose the tenements of New York don't lend themselves to all that many musical storylines, unless you're making West Side Story. All in all, Cleve concludes, "when you see wonderful episodes like Ralph being blackmailed by a senorita or being duped into becoming a Santa Claus bookie, somehow you like the show the way it is—warts and all."

l l l

Now that the inaugural Super Bowl (and yes, that's what TV Guide has called it) is over, Stanley Frank is here to answer the big question: no, not which league is best, but which network won the TV game—CBS, with their broadcasting team of Ray Scott, Jack Whittaker, and Frank Gifford, or NBC's long-running announce booth of Curt Gowdy and Paul Christman.

As you probably know, both networks televised the game, with an agreement that they would alternate coverage of future games. With the largest U.S. audience ever to watch a sporting event on the line, the stakes were high. During the regular season, CBS outdrew NBC by two to one, which isn't surprising considering the NFL is not only the more established league but has the larger television markets; it was thought that CBS needed to win by about five ratings points in order to show it had retained its core audience, while NBC needed to keep things close or else they'd have trouble selling the AFL to advertisers next season.

As is typical when ratings are involved, there was good news for everyone. According to the Arbitron overnight figures, CBS scored a "smashing" victory, drawing 59 percent of the football audience and besting NBC by more than seven points; NBC countered with Nielsen figures that showed them trailing CBS by only 1.2 points in the critical New York City market. (The final ratings: CBS won the Nielsens 22.6 to 18.5, and the market share 43-36.)

How did the announcers do? Frank's analysis is that NBC's Gowdy betrayed his rooting interest in the AFL's Kansas City Chiefs, "flout[ing] the objectivity a reporter is supposed to observe," but he did inject excitement into the game while the score was still close. (I don't find that unexpected, considering that Ray Scott, who did the first half of the game for CBS, is known for his minimalist, "just the facts" style of play-by-play.) The NFL's Green Bay Packers made Gowdy look bad several times; after proclaiming that "Green Bay's famed ground game has been stopped!" Gowdy watched as Green Bay's Jim Taylor rolled 14 yards on the ground for a touchdown. He was, Frank says, "a prophet without honor and a partisan without a winner." Better was Gowdy's color analyst, Paul Christman, and it's too bad that more aren't familiar with his work today. He was the first announcer with the ability to, in Frank's words, "explain what was happening clearly and concisely, with a minimum of technical gobbledygook." He shrewdly anticipated plays and wasn't afraid to lay it on the line; with the Packers leading 7-0 and the Chiefs threatening, he called the next play the pivotal moment of the game, saying, "Kansas CIty will have to prove itself and score to have a chance to win."

CBS, in general, displayed a more impartial voice; Gifford "almost dislocated a vertebra bending over backward to laud the Chiefs and make character for his firm with AFL owners," no doubt hoping it would improve the network's chances of getting the whole TV package after the leagues merge. The inexperienced Gifford, a rookie announcer, struggled working the first half with the bare-bones Scott, but he became more comfortable as the game progressed, and worked well with second-half play-by-play man Jack Whittaker. Although he didn't have the analytical acumen of Christman, and he sometimes seemed surprised that the Chiefs were, in fact, an accomplished professional football team ("The Chiefs came to play football," he remarked "lamely" after they'd tied the game), he was particularly good at explaining the emotional aspects of the game; Frank feels that "his human-interest touches brightened what had become a dull contest" by the fourth quarter. Perhaps he knew what Kansas City players were feeling, Frank concludes; after all, in 1961 "Gifford's Giants met the Packers for the NFL title and were clobbered, 37-0."

Why did I spend so much time on this? Well, 29 of the top 30 most-watched television broadcasts of all time have been Super Bowls. The cost of a 30-second commercial in 1967 was $42,000; last year, it was between $6.5 and $7 million.

l l l

I missed the point of The Monkees when they debuted in 1966. Sure, I watched the show from time to time, but since I wasn't a fan of The Beatles, the comparisons were lost on me. And since I wasn't a teenage girl, the "cute" factor was a non-issue as well. In fact, now that I think of it, I probably saw the show more often on Saturday mornings than I did in the original airing. I was never a fan, but neither did I dismiss them out of hand.

Leslie Raddatz's article rehashes everything we know about the group: the Daily Variety ad ("MADNESS!! Auditions—Folk & Roll Musicians-Singers—Running parts for 4 insane boys, age 17-21.") and the descriptions of our four heroes (Davy, "the little one"; Mike, "the one with the hat"; Mickey, "who was Circus Boy when he and TV were both young"; and Peter, "the shy one with the dimples."), and we're not surprised to find that the four not only are referred to as "kids" by everyone, "they act like kids, and that's the way they seem to think of themselves." But as Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, the co-producers, point out, their goal was not to find four actors to play The Monkees, but to be The Monkees.

Each one of them has his own story; Davy was a jockey in England as well as an actor; under contract to Columbia, he's the only one of the four who wasn't cast from the Daily Variety ad. Peter flunked out of college and worked as a kitchen boy while he sang in coffee houses; he originally didn't want to audition, "but I had let my hair grow in the Village, so I was ready for the part." Mickey was part of an acting family and starred in Circus Boy when he was 10; Raddatz describes him as "the only one who seems to be acting, rather than just being himself." Even at this early stage in their history, Mike is seen as different from the other three; he has "a brooding quality," and is the only one of the four who is "reluctant to talk about himself." He's worn his hat for five years, but "Now that I've got to wear it, I'm gettin' tired of it."

The Monkees cut quite a swath through pop culture in the 1960s, even though the series only runs for two seasons, with a total of 58 episodes. The show makes a comeback in 1986, thanks to a marathon on MTV, and it never really dropped off the map after that, with the group, in various incarnations, touring around the country. And yet, I don't know if anyone truly appreciated the impact it made until Davy Jones's unexpected death in 2012, and the overwhelming outpouring of grief and memories across social media. Sure, the Monkees had been popular, and Davy's death was a shock, but I think very few people were prepared for the tidal wave of warmth and affection that resulted. There were those, I know, who didn't understand, maybe couldn't understand, how a silly TV show could mean so much to so many people. And yet there it was. We saw it again in 2019 with Peter Tork's death, and in 2021 when Mike Nesmith died, leaving only Mickey Dolenz.

And if that seems impossible to believe, well, Mickey's 77 now, and while he should have many years to go, eventually that time will come, and then The Monkees will be just a memory, four young men frozen in time on video. Even the thought of that seems impossible, but there it is. And then all of us will look back then, back to the days when we, too, were young.

l l l

All right, let's look at what's on this week, and see if they interest anyone besides me.

Words mean things and they tell stories, and on Saturday's Lawrence Welk Show (8:30 p.m. ET, ABC), the story is told herein in the description of tonight's show, "A tribute to the late Walt Disney." Disney died the previous December 15, six weeks past, and the phrase "the late Walt Disney" must still have looked very strange (and very sad) to a public that had become so used to him and fond of him.

You may have notice that there's no "Sullivan vs. Palace" this week; The Hollywood Palace is preempted tonight by the "Deb Star Ball," telecast live from the Hollywood Palladium and hosted by Steve Allen and Jayne Meadows. It's kind of hard to describe just what this event is; think of it as something like a beauty pageant with actresses. Donna Loren describes it like this: "Each year, ten of Hollywood’s most promising young actresses were dubbed Deb Stars by the Hollywood Makeup Artists and Hair Stylists Guild and were presented with the coveted 'Debbie' at the Guild’s annual ball." Past debs include Yvette Mimieux, Mary Ann Mobley, Yvonne Craig, Raquel Welch, Sally Field, and, of course, Donna Loren. This year's debs include Linda Kay Henning (Petticoat Junction), Debbie Watson (Tammy), Celeste Yarnall (The Nutty Professor), and E.J. Peaker (next season she'll be in That's Life). Not a bad lineup. We won't ignore Ed, though; his guests on Sunday's show (8:00 p.m., CBS) include the comic Smothers Brothers; the folk rocking Mamas and Papas, who sing "Words of Love"; singers Enzo Stuarti and Gale Martin (Dean's daughter); comedians Nipsy Russell and George Carlin; and Your Father's Mustache, banjo-playing singers. Frankly, I would have liked the Palace's chances.

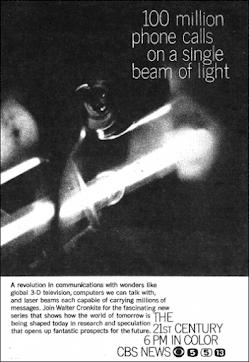

Also on Sunday, we see the transition of CBS's long-running 20th Century to the forward-looking 21st Century (6:00 p.m.). Still hosted by Walter Cronkite, tonight's debut episode is "The Communications Explosion," looking at the radical innovation of fiberoptics, which will allow "100 million phone calls on a single beam of light."

I got to thinking about Monday's episode of Run for Your Life (10:00 p.m., NBC), in which Paul (Ben Gazzara) is defending an ex-cop charged with murder. (Remember, Paul Bryan is a lawyer by profession.) In the series, Paul has only one to two years to live due to his disease. Today, the average time it takes for an accused murderer to go to trial can take one to two years. Knowing that, would you want to hire Paul as your attorney? Mind you, I'm not criticizing the author of this script; 55 years ago, this probably wouldn't have been an issue. After all, Perry Mason gets his clients off in a matter of weeks.

On the other hand, here, I think, is an example of why The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. failed: "April and Mark join a rock 'n' roll combo to protect Prince Efrem, the swinging heir apparent to a Tyrolean throne. The rockin' Daily Flash do 'My Bulgarian Baby. ' " (Tuesday, 7:30 p.m., NBC) This sounds to me more like a skit on a Bob Hope special, with Bob playing Prince Efrem. Help me out on this; would this ever have been hip? At least Vito Scotti is one of the guest stars; that helps. Occasional Wife, which airs a half-hour later on NBC, has a far more plausible plot: the man whose female friend agrees to pose as his wife in order for him to advance in the corporation.

Speaking of Hope, Wednesday's episode of Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre is notable in that the director of "The Lady Is My Wife," is Sam Peckinpah. Not surprisingly, the story is a Western, with Bradford Dillman, Jean Simmons, and Alex Cord. Peckinpah actually did quite a lot of television early in his career, including The Rifleman; he created the Brian Keith Western The Westerner in 1960, and had a major success in 1966 with "Noon Wine" on ABC Stage 67. but at the time of this Hope episode, he's also started to make a mark on the big screen, with both Ride the High Country and Major Dundee.

|

| An ad from the 1964 airing. |

On Friday night, NET Playhouse presents Roman Polanski's feature film debut, 1962's Knife in the Water (8:00 p.m., NET), a psychological thriller about two men fighting for the same woman. Ah, an eternal story, but not the way Polanski does it. After that, you can get The Avengers' take on The Invisible Man, as Steed and Mrs. Peel check out the case of two Slavic (i.e. Soviet) agents who've obtained an invisibility formula (10:00 p.m., ABC). You won't be able to see through that plot.

l l l

MST3K alert: Gunslinger (1953). "The female owner of the town saloon imports a killer to slay the town's female marshal. John Ireland, Beverly Garland, Allison Hayes." (Thursday, 6:00 p.m. WEMT) The saloonkeeper is Allison Hayes; the gunman is John Ireland; the marshal is Beverly Garland, the producer/director is Roger Corman. Need we say any more? TV

I, too, discovered the Monkees from their Saturday morning syndication run. While I was lukewarm on the series, I thought the music was was wonderful. Still do.

ReplyDelete