Some weeks are easier than others, and this is one of them. The

has one of the greatest dancers of all time hosting, one of the greatest mimes of all time as a guest, and one of the great belters of all time. With Fred Astaire, Marcel Marceau, and Ethel Merman, the show hardly needs one of the smoothest singers of the time, Jack Jones, but why not? Ed's big gun is Pearl Bailey, no slouch to be sure, but on mesasure this really isn't a contest:

.

l l l

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, TV Guide's weekly reviews were written by the witty and acerbic Cleveland Amory. Whenever we get the chance, we'll look at Cleve's latest take on the shows of the era.

One of the revealing aspects of the TV Guide collection is finding out how some of today's best-loved shows were, on first glance, not that big a deal. You might recall that Cleve was no great fan of Carol Burnett when her show first premiered, but it wound up outlasting his column. The same can't be said for I Dream of Jeannie; it only runs for five seasons, but it's been in reruns ever since, and remains one of the most popular of the classic TV sitcoms. To be fair, Our Critic doesn't hate the show, which he calls "the NBC answer to ABC's Bewitched (an unfair comparison, I'd say); in fact, he says that Jeannie, "which is only moderately well acted and directed, has at least three redeeming features."

Not surprisingly, first and foremost on that list (as it is with you, I'm sure) is Barbara Eden. Not only is she "a very good-looking girl," she's also capable of all the special-effects magic that Bewitched and other shows produce. And third, the show occasionally veers into actual satire; witness how Tony (Larry Hagman) can make Jeannie go back into her bottle any time he doesn't want her around. That would, Cleve points out, "make her the ideal wife." That's what Tony's friend Roger (Bill Daily) thinks, anyway, but Tony warns him not to go there. "Your friends will turn on you. Their wives will hate you. Do you think they’re going to watch her treat you with kindness and understanding and compassion? Do you think they’ll let her destroy everything they stand for?" Ouch.

Amory enjoys the fact that Jeannie, being a very jealous genie, which allows the writers to have a field day, as in the episode where Jeannie threatens to turn one of Tony's old girlfriends into a pillar of salt, whereupon Tony replies by threatening to pour ink in her bottle. She desperately wants to marry Tony; after being single for 2500 years, "I don't want to be an old maid." There's also a streak of michievousness in her, which can make things miserable for Tony, Roger, and Dr. Bellows (Hayden Rourke), and this, he says, "makes I Dream of Jeannie bearable for the rest of us." Now I grant you, this is the show's first season, so we don't know if Cleve modified his views as the series progresses. One would hope so; otherwise, Jeannie might just make one particular critic disappear.

l l l

The latest effort of the American space program, the launch of Gemini VIII, is scheduled for Tuesday, March 15; it actually comes off the following day, following the successful launch of the Atlas-Agena target vehicle with which the Gemini capsule is scheduled to perform various docking manuevers. Network coverage begins with the twin launches on Wednesday morning, and continuesentire with the planned docking in the late afternoon. The networks also warn that programs "may be pre-empted" for coverage of the spaceflight, and if you know anything about Gemini VIII, you know that this promise was more than fulfilled.

The two first-time astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott, successfully dock with the Agena (the first such docking in history), but shortly after passing out of communications range, the coupled spacecrafts began to rotate along all three axes at a high rate of speed. Concerned that the rate of roll could cause the Agena to explode, Scott uncoupled the Gemini, whereupon the tumbling increased violently, along roll, pitch, and yaw, at a rate of 60 revolutions per minute. Charts and checklists flew around the cabin, and the unfiltered sunlight came through the windows with the effect of a strobe. With the astronauts close to blacking out, Armstrong decided to use the craft's reentry thrusters to stop the spinning. It was a bold, but necessary gamble; Scott later said of Armstrong, "The guy was brilliant. He knew the system so well. He found the solution, he activated the solution, under extreme circumstances ... it was my lucky day to be flying with him." Once the re-entry controls had been activated, mission rules required that the flight be aborted, and Gemini VIII prepared for an emergency landing.

Much like the Apollo 13 mission just over four years later, the networks interrupted regular programming—The Virginian on NBC, Batman on ABC, and, ironically, Lost in Space on CBS. Reentering over China, the craft landed safely in the Pacific; although it was still daytime at the splashdown site, it was the first to take place at night in the continental United States. The crisis itself had lasted for about 30 minutes; the entire flight, which had been planned for three days, ended after around ten hours.

l l l

The Open Mind, hosted by Richard Heffner, debuted on public television in 1956, dedicated to "thoughtful excursion into the world of ideas." It reminds me of David Susskind's Open End, in that it tackles topics that you don't always see on programs like, say, Meet the Press. On Saturday night (8:00 p.m., KQED), we've got one that wouldn't be out of place today: "Are Flying Saucers Only Science Fic- tion?" And in fact, the program could still take up the topic (and include foreign balloons in the bargain!) since The Open Mind is still on the air, the 13th longest-running television program in American history, about to enter its 67th season and hosted by Richard Heffner's grandson, Alexander.

One other note about Saturday: NBC's

Saturday Night at the Movies presents the American TV debut of

A Place in the Sun (9:00 p.m.), based on Theodore Dreiser's novel

An American Tragedy, and starring Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor, and Shelley Winters.

Saturday Night at the Movies expands to two and-a-half hours for this movie, and a note at the end of the listing explains why: "The Los Angeles Superior Court recently ruled that this film could not be televised if its artistic qualities were harmed. NBC is presenting it without cuts." That would have been quite something, considering the editing of movies due to length or content was a common, and controversial, practice back then.

Spring is in the air, and with it the promise of baseball; KTVU gets things started with a spring training game between the San Francisco Giants and Cleveland Indians, live from Phoenix (Sunday, 12 noon). Sunday evening, The Bell Telelphone Hour (6:30 p.m., NBC) presents an hour of music from American movies, hosted by Ray Bolger, and starring Robert Merrill, André Previn, and musical-comedy performers Ann Miller, Gloria De Haven, Peter Marshall, Constance Towers and Judi Rolin. The Telephone Hour remains one of the 1960s last weekly programs to be done live on a regular basis.

A very funny parody of

The Untouchables is the highlight on

The Lucy Show (

Monday, 8:30 p.m., CBS), with Robert Stack as an FBI agent who recruits Lucy to pose as the girlfriend of a soon-to-be-released-from-prison gangster, played by Bruce Gordon. Steve London, who played one of Eliot Ness's men on

The Untouchables, is Stack's assistant, and the narration is provided, as it was then, by Walter Winchell. They even use the same theme music—but then, since Desilu produced

The Untouchables, they shouldn't have had any trouble getting the rights. Stack and Gordon were good friends; Gordon never shied away from his casting as gangster Frank Nitti, so I wouldn't be surprised if they had a great time filming this. You can watch it all

here.

Tuesday's 11:30 p.m. movie on KGO (not to be confused with the All-Night Movie, which doesn't start until 1:20 a.m.) is The Private Lives of Adam and Eve, which I would swear I'd seen on a program guide for an adult movie channel, but apparently not, since it's making its Bay Area TV debut. It's co-directed by Mickey Rooney, and it tells the allegorical story of a group of people seeking refuge from a storm in a country church. Rooney stars as Nick, aka the Devil, while who else could possibly play Eve but Mamie Van Doren? Need I include the fact that it's a comedy?

We don't know for sure what actually aired on Wednesday, what with the coverage of the Gemini VIII emergency, but the Bob Hope Comedy Special (9:00 p.m., NBC) sounds as if it would have been a good bet; skits include Phyllis Diller in "Pagoda Place" as a woman who's remarried, only to find out her first husband is still alive; an Academy Awards spoof with Jonathan Winters as Rock Surly, an actor accused of bumping off his fellow nominees; and Lee Marvin, one of those real-life nominees, as Slim Premise, a sissified gunfighter, and Bob as El Crummo, a bandit chief.

Part one of this week's Batman adventure was interrupted by last night's bulletins (at least twice, according to oral histories), but that won't stop ABC from airing part two on Thursday (7:30 p.m., ABC). It's called, unironically, "Better Luck Next Time," and it wraps up the first appearance of the one and only Catwoman (Julie Newmar). That's on up against The Munsters (7:30 p.m., CBS), which presents a rare look at the show's backstory, as Herman is visited by Dr. Frankenstein IV, decendant of the man who assembled him, and an evil Herman lookalike named Johann. Now that's scary!

l l l

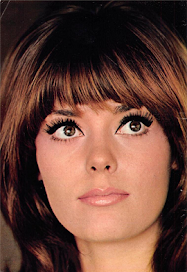

Friday night's episode of

Camp Runamuck (7:30 p.m., NBC) features Spiffy (David Ketchum) falling under an oriental philosophy that causes him to make a truce with the ladies of Camp Divine. And that leads us to this week's starlet, Nina Wayne, who plays the "curvaceous counsellor" of the girls' camp, Caprice Yeudleman—also known as "the tall show girl with the tiny voice."

She didn't start out for a career in show business. Believe it or not, and there's no reason not to believe it, she and her sister Carol were afflicted with weak ankles and skinny legs—oh, and they were also pigeon-toed. Their uncle, a doctor, suggested they try ice skating, and they would up good enough at it that they joined the Ice Capades when Nina was 15. The Wayne Sisters toured with the Capades for two years, finally hanging up the skates when Carol fell and injured her knee.

From there, Nina moved first to Vegas and then Chicago, where she became "a model by day and a dancer by night"; her mother's only comment was that "Daddy and I would prefer that you wear a few more beads." She started working with Van Johnson in his nightclub act, which led to an appearance on The Tonight Show, where Johnny was charmed by her "kind of coo-coo way of speaking," and a comedy style that he described as "early idiot." (When Carson asked her, "How does it feel to work without any clothes on?" Nina answered, "Naked." David Swift, putting together a cast for a new sitcom, happened to see that appearance ("She has the voice of a grape comng out of a banana"), and two day slater she was doing the pilot for Camp Runamuck.

She wants to be a "big star," but her acting coaches are under instructions not to tamper with that voice; Swift says, "She has almost an armor of naiveté, translated directly without being filtered." And while Camp Runamuck, scheduled opposite The Wild Wild West and The Flintstones, won't be around much longer, she's hoping to be heard from again. In fact, her career continues until the mid-'70s, including the movie The Night Strangler and a career on the stage. She marries, and divorces, John Drew Barrymore, the father of Drew Barrymore. And, in case you hadn't figured it out from all the clues in the article—a curvaceous figure, a little voice, a last name of Wayne, and a sister named Carol—that sister is, indeed, Carol Wayne, the Tea Time Movie sidekick to Carson's Art Fern. Small world, so to speak.

l l l

MST3K alert: The Indestructible Man (1956). "A death row inmate double-crossed by his lawyer gets a chance for revenge when a bizarre experiment brings him back to life. Lon Chaney, Casey Adams." (Friday, part of KGO's All Night Movie) Look for a small but pivotal role played by Joe Flynn, who's probably glad he's better-known for McHale's Navy. TV