|

| Left to right: Gary Merrill, Cornelia Otis Skinner, Joseph Wiseman, Carmen Mathews, and Jack Gilford |

W

e’re viewing a documentary being shown to us in the present time—that is, 1990. The presenter (Linda Decoff), an icy young woman speaking with the cold precision of one totally convinced of the truth of her words, explains that what we are about to see is based on "an old-style written report" describing "an outmoded culture." The purpose of the presentation is to counteract the rising influence of this "report," which is being spread by the underground press, especially effecting "those now reaching 40." It is important to counteract this propaganda now, before it can destabilize the new society and the technological rationality that has made it what it is today; before it can lead to the return of love, compassion, and similar feelings—feelings that cannot be permitted to rise again under the appearance of "humanity."

What follows is the story They don’t want you to see.

It begins in a beachfront house in a deserted area somewhere on the Northeastern coast of the United States. It serves as the home for five artists: Barney (Gary Merrill), the oldest of the five, the painter; his wife Annie (Carmen Mathews*), the group’s earth mother, a giver rather than a taker; Joey (Jack Gifford), the popular musical-comedy songwriter; Joseph Wiseman, the orchestra conductor; and Kate (Cornelia Otis Skinner), the novelist who has kept the written record of their time in exile—the "report" of the documentary.

*Maureen O’Sullivan was originally cast in this role, but was forced to bow out due to illness and was replaced by Mathews, a distinguished actress in her own right.

It has been twenty years since They came into power, the rebellious and computerized youth, the "now" generation. Taking advantage of violence and racial unrest in the major cities, of continued military adventures in Vietnam and elsewhere, of the private gain triumphing over the public need, "They finally got themselves together in a unified national organization and started to draw plans for the takeover at the next elections." For it was not a putsch, not a revolution, but an electoral victory that They had won. And after that, the new laws meant to facilitate the institution of the new society.

The old, They had determined, were the most resistant to the progress They had proposed. The young blamed them for these problems—but then, since they had already cut themselves off from their parents, how could they know many of them had opposed all this as well? And so, since the old were the most resistant to the progress They were proposing, a new constitution was put into effect. The newly created Age Agency instituted a mandatory retirement age of 50; those beyond that age were to be isolated from the young, including their own families, and from life in general.

"We were permitted to live either in a community or in our own houses," Kate remembers, "provided that these houses were isolated from urban centers and concentrations of the young, and reasonably close to computerized service centers especially set up to provide the needs of the old, specifically food and medical attention for minor afflictions." They will remain here, with no radio, no television, no means of transportation except to bring groceries home: a small electric car (!) with a maximum speed of twenty-five miles an hour and a range dictated by the amount of batteries.

It’s not forever, though, for as the old were seen as "a drain on society," they would be subject to periodic computerized medical examinations, until they become seriously ill or reach the age of 65, whichever occurs first, when they are given a choice: self-disposal or compulsory liquidation, they called it. "It was very liberal of Them," comments Kate, "considering that every year of our useless lives was costing them that much more money and administration needed for the new exiles. The computer saw to that, as it saw to everything."

By now, an apparent majority have given up, their shock and denial giving way to numbness and then acceptance, a macabre version of the stages of grief. They wanted "none of the complications of the outside world," and accepted the idea of "easeful death," as it was euphemistically called, helped by an unlimited supply of drugs, cigarettes, and booze which They had provided, in hopes that they would bring about their own demise.

But not these longtime friends, who have lived here in isolation, defiant members of that "outmoded culture" that They rebelled against. The ramshackle old house had been a summer place for Kate and her husband Jeff before They had taken over, but then Jeff had committed suicide by walking into the tide. The others had been allowed to join Kate in exile, given their prominence in the arts—a magnanimous gesture, it would seem, but then it simply afforded more space in the camps for others. Practical, you know.

There is solace in their being together, in sharing their exile, their memories, their pain, their values. They engage in activities to keep them mentally and physically engaged, sense-sharpening games such as Blind Day, Deaf Day, and One-Arm Day. Barney works in his garden, Joey and Lev play the piano, Annie spends her time in the kitchen, and Kate documents their discussions. But mostly they spend their time talking. Discussing the heritage of the past. Preparing a manifesto of sorts, a statement of ideals. All of which Kate faithfully transcribes, best as she can, in case there is anyone out there who might someday see and read it (if anyone reads anymore), to find out what their "outmoded culture" was all about.

And they talk about how it all started, each through their own experiences. For Barney, it was the beginning of the modern art movement: "The junkmen and fakers who call themselves artists had no humility. They said, ‘Don’t paint what you see; paint what you feel. . . Back to your navels, boys, and yourselves!’ "

According to Joey, "It was hearing my songs used as commercial jingles to sell cars or soft drinks, it was the dirty lyrics sung by dirty bums, it was going to a show that was made of four-letter words and repulsive people and then reading next day how great it was, how ‘significant.’ It was a lot of rank amateurs making it overnight."

For Lev it was the rise of the "barbarians" and their atonal music, filled with tape and weird noises, what he calls "electronic masturbations." "I really liked some of their songs, until they amplified them to the point of insanity . . . the rape of the ear. . . before songs became grunts." It’s a total depersonalization of art, of feeling, of human warmth.

("Individual and subjective criticism in all the arts has been supplanted by our infallible computer value scales," our presenter reminds us.)

Kate remembers how They took over the universities: "They first demanded the right to determine what was to be taught, and then who should teach them." They were "hostile and incoherent, contemptuous of law, using force (as the only tool of the spiritually illiterate), screaming against the counter-force they brought on them—every instinct in us froze." It was a totalitarian breed, one that showed no mercy.

Annie recalls the moment that she first became afraid of the young, tough and hard and dirty-mouthed. "Were our beliefs and convictions so alien to them? They blocked out the past so they could move ahead."

"Of course," Lev replies disdainfully, "because only the present exists for them, they are the children of Now."

Joey recalls a young painter saying, "For this generation, history is about ten seconds ago."

"We should have known," Kate remembers, "long before They actually took over that something of the sort was going to happen, but people never really believe anything until it does happen."

And then one day they come upon a young man (Robert McLane) washed up on the shore, thin, bearded, with long, scraggly hair. He’s near death when they find him; they revive him, but find that he can neither read, write, or speak. They decide to call him Michael.

"We were told daily that mind—logic, reason—meant nothing and that only sensation counted," Kate remembers. "Words were of no importance, except to the intellectual arbiters who used them to tell us this." And yet words are all they have, and so they continue to use them.

As time passes, the rest find themselves using Michael as a surrogate audience, finding that they speculate about him when he is around, and talk about him when he is not. They still don’t know where he came from, or how he got there: an escapee from a youth camp’ a refugee from the cities’ perhaps someone from outer space, maybe even an angel of death. (So inexplicable is his appearance, even the last two seem plausible.) Because his association with them would be against all the isolation rules that They set up, the others are careful to hide him when the patrols come by.

He helps Barney in the garden, and Barney says the boy seems to have an aptitude for drawing—he’s particularly given to doing line drawings of a television set—but is it something he learned, something he’s observed, or is it something instinctive? But does he understand what they are saying to him? And even if he does, do their words, the testimony they are giving, mean anything to him? But he seems comforted to be in their presence. Their discussions continue. What’s the state of the world today? They are convinced that the divisions into which the country had fractured had grown wider, more numerous, more deadly: Black/White, Right/Left, Reds/Us, Rich/Poor, Old/Young, Man/Woman. There’s no doubt that They felt let down by the older generation, blamed them, held them in contempt, demeaned them, stripped them of their worth, ignored their existence. To Barney, it’s even worse than hate. "Most of the time we didn’t exist, we were dead before we died!" The barbarian code, Lev puts it; do unto others as they have done unto you." They’re left to debate what they call Articles of their belief, a kind of last testament even though they’re not sure anyone will ever read it. But even there, it becomes more and more difficult to say what any of it means anymore.

Although this situation was never going to approach anything like permanence, the truth of the impending end becomes ever more apparent, ever more real. The physical and mental exercises which the group have for so long undertaken to maintain their energy and defiance-- Blind Day, Deaf Day—have gradually, one by one, dropped by the wayside. Finally, a day comes, as we knew from the beginning it must. Barney’s declining health—his harsh cough, his difficulty speaking, his increasing frailness—has become impossible to ignore; Annie is terrified it’s cancer, and none of the others are foolish enough to try and talk her out of it. It will be impossible for him to pass his next physical, and that means an automatic sentence of death. It hurts her too much for her to watch him suffer any more; she’s convinced that any moment the truck from the Age Agency will be there to take him away.

The implications of this are clear for everyone. Barney’s time was limited anyway; he was the oldest of the group. The others, except for Annie (who has no desire to go on living without Barney) are under no immediate obligation; they still have some time left, and no matter what anyone says in the abstract, when the time comes, nobody really wants to die. However, they have always resolved that when it was time, they’d all go together; they’ve been together for too long, and waiting for Them to come and do the job would be an admission of defeat. They latch on the method of delivery: drugged whiskey, "Pills and liquor."

The final night becomes part wake, part elegy. Kate sums it up for the rest when they discuss the kind of message they want to leave if They ever read it. "That you fight for your humanity and dignity. That you refuse to be bent, folded, spindled, or mutilated by any machine. That you perceive and love the nature of the universe inside and outside of yourself." They say their toasts and drink their poison—and then, as they had wished, after they have lost consciousness Michael sets fire to the house and flees with the manuscript, delivering it to the underground. He had understood after all.

But—there’s one last tragic scene, one final ironic act. Because there could be no winner it a story like this, and how else could it end? For as They grew older ("deprived of their past," Mannes writes, "and fearful of their future."), They began to realize that Their laws, sooner or later, would apply to Them as well.

Thus, whether through enlightenment or self-preservation, the government had been toppled a few weeks before the final farewell, and the laws regarding age had been repealed.

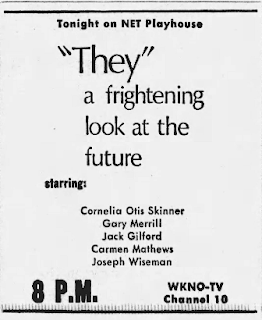

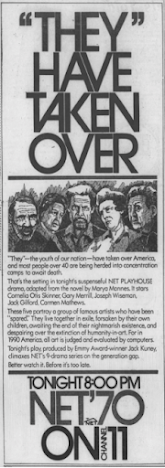

"They," based on Marya Mannes’ controversial 1968 novel (and adapted by Mannes and Charles LeMay), originally aired on the Public Broadcasting Service’s NET Playhouse on April 17, 1970 as the final episode in an eight-part sub-series of plays titled "A Generation of Leaves," dealing with what was popularity known at the time as the Generation Gap. Jac Vanza, executive producer of NET Playhouse, described the central theme of all eight episodes as "the seemingly world-wide breach between youth and elders." "The younger generation questions its inheritance," said Vanza, "the older generation questions the values of the younger generation and herein lies the communications gap. Which is, by the way, nothing new."

What follows is the story They don’t want you to see.

I

It begins in a beachfront house in a deserted area somewhere on the Northeastern coast of the United States. It serves as the home for five artists: Barney (Gary Merrill), the oldest of the five, the painter; his wife Annie (Carmen Mathews*), the group’s earth mother, a giver rather than a taker; Joey (Jack Gifford), the popular musical-comedy songwriter; Joseph Wiseman, the orchestra conductor; and Kate (Cornelia Otis Skinner), the novelist who has kept the written record of their time in exile—the "report" of the documentary.

*Maureen O’Sullivan was originally cast in this role, but was forced to bow out due to illness and was replaced by Mathews, a distinguished actress in her own right.

It has been twenty years since They came into power, the rebellious and computerized youth, the "now" generation. Taking advantage of violence and racial unrest in the major cities, of continued military adventures in Vietnam and elsewhere, of the private gain triumphing over the public need, "They finally got themselves together in a unified national organization and started to draw plans for the takeover at the next elections." For it was not a putsch, not a revolution, but an electoral victory that They had won. And after that, the new laws meant to facilitate the institution of the new society.

The old, They had determined, were the most resistant to the progress They had proposed. The young blamed them for these problems—but then, since they had already cut themselves off from their parents, how could they know many of them had opposed all this as well? And so, since the old were the most resistant to the progress They were proposing, a new constitution was put into effect. The newly created Age Agency instituted a mandatory retirement age of 50; those beyond that age were to be isolated from the young, including their own families, and from life in general.

"We were permitted to live either in a community or in our own houses," Kate remembers, "provided that these houses were isolated from urban centers and concentrations of the young, and reasonably close to computerized service centers especially set up to provide the needs of the old, specifically food and medical attention for minor afflictions." They will remain here, with no radio, no television, no means of transportation except to bring groceries home: a small electric car (!) with a maximum speed of twenty-five miles an hour and a range dictated by the amount of batteries.

It’s not forever, though, for as the old were seen as "a drain on society," they would be subject to periodic computerized medical examinations, until they become seriously ill or reach the age of 65, whichever occurs first, when they are given a choice: self-disposal or compulsory liquidation, they called it. "It was very liberal of Them," comments Kate, "considering that every year of our useless lives was costing them that much more money and administration needed for the new exiles. The computer saw to that, as it saw to everything."

By now, an apparent majority have given up, their shock and denial giving way to numbness and then acceptance, a macabre version of the stages of grief. They wanted "none of the complications of the outside world," and accepted the idea of "easeful death," as it was euphemistically called, helped by an unlimited supply of drugs, cigarettes, and booze which They had provided, in hopes that they would bring about their own demise.

But not these longtime friends, who have lived here in isolation, defiant members of that "outmoded culture" that They rebelled against. The ramshackle old house had been a summer place for Kate and her husband Jeff before They had taken over, but then Jeff had committed suicide by walking into the tide. The others had been allowed to join Kate in exile, given their prominence in the arts—a magnanimous gesture, it would seem, but then it simply afforded more space in the camps for others. Practical, you know.

There is solace in their being together, in sharing their exile, their memories, their pain, their values. They engage in activities to keep them mentally and physically engaged, sense-sharpening games such as Blind Day, Deaf Day, and One-Arm Day. Barney works in his garden, Joey and Lev play the piano, Annie spends her time in the kitchen, and Kate documents their discussions. But mostly they spend their time talking. Discussing the heritage of the past. Preparing a manifesto of sorts, a statement of ideals. All of which Kate faithfully transcribes, best as she can, in case there is anyone out there who might someday see and read it (if anyone reads anymore), to find out what their "outmoded culture" was all about.

And they talk about how it all started, each through their own experiences. For Barney, it was the beginning of the modern art movement: "The junkmen and fakers who call themselves artists had no humility. They said, ‘Don’t paint what you see; paint what you feel. . . Back to your navels, boys, and yourselves!’ "

According to Joey, "It was hearing my songs used as commercial jingles to sell cars or soft drinks, it was the dirty lyrics sung by dirty bums, it was going to a show that was made of four-letter words and repulsive people and then reading next day how great it was, how ‘significant.’ It was a lot of rank amateurs making it overnight."

For Lev it was the rise of the "barbarians" and their atonal music, filled with tape and weird noises, what he calls "electronic masturbations." "I really liked some of their songs, until they amplified them to the point of insanity . . . the rape of the ear. . . before songs became grunts." It’s a total depersonalization of art, of feeling, of human warmth.

("Individual and subjective criticism in all the arts has been supplanted by our infallible computer value scales," our presenter reminds us.)

Kate remembers how They took over the universities: "They first demanded the right to determine what was to be taught, and then who should teach them." They were "hostile and incoherent, contemptuous of law, using force (as the only tool of the spiritually illiterate), screaming against the counter-force they brought on them—every instinct in us froze." It was a totalitarian breed, one that showed no mercy.

Annie recalls the moment that she first became afraid of the young, tough and hard and dirty-mouthed. "Were our beliefs and convictions so alien to them? They blocked out the past so they could move ahead."

"Of course," Lev replies disdainfully, "because only the present exists for them, they are the children of Now."

Joey recalls a young painter saying, "For this generation, history is about ten seconds ago."

"We should have known," Kate remembers, "long before They actually took over that something of the sort was going to happen, but people never really believe anything until it does happen."

And then one day they come upon a young man (Robert McLane) washed up on the shore, thin, bearded, with long, scraggly hair. He’s near death when they find him; they revive him, but find that he can neither read, write, or speak. They decide to call him Michael.

II

|

| Robert McLane (seated) with (L-R) Cornelia Otis Skinner, Gary Merrill, and Joseph Wiseman |

As time passes, the rest find themselves using Michael as a surrogate audience, finding that they speculate about him when he is around, and talk about him when he is not. They still don’t know where he came from, or how he got there: an escapee from a youth camp’ a refugee from the cities’ perhaps someone from outer space, maybe even an angel of death. (So inexplicable is his appearance, even the last two seem plausible.) Because his association with them would be against all the isolation rules that They set up, the others are careful to hide him when the patrols come by.

He helps Barney in the garden, and Barney says the boy seems to have an aptitude for drawing—he’s particularly given to doing line drawings of a television set—but is it something he learned, something he’s observed, or is it something instinctive? But does he understand what they are saying to him? And even if he does, do their words, the testimony they are giving, mean anything to him? But he seems comforted to be in their presence. Their discussions continue. What’s the state of the world today? They are convinced that the divisions into which the country had fractured had grown wider, more numerous, more deadly: Black/White, Right/Left, Reds/Us, Rich/Poor, Old/Young, Man/Woman. There’s no doubt that They felt let down by the older generation, blamed them, held them in contempt, demeaned them, stripped them of their worth, ignored their existence. To Barney, it’s even worse than hate. "Most of the time we didn’t exist, we were dead before we died!" The barbarian code, Lev puts it; do unto others as they have done unto you." They’re left to debate what they call Articles of their belief, a kind of last testament even though they’re not sure anyone will ever read it. But even there, it becomes more and more difficult to say what any of it means anymore.

Although this situation was never going to approach anything like permanence, the truth of the impending end becomes ever more apparent, ever more real. The physical and mental exercises which the group have for so long undertaken to maintain their energy and defiance-- Blind Day, Deaf Day—have gradually, one by one, dropped by the wayside. Finally, a day comes, as we knew from the beginning it must. Barney’s declining health—his harsh cough, his difficulty speaking, his increasing frailness—has become impossible to ignore; Annie is terrified it’s cancer, and none of the others are foolish enough to try and talk her out of it. It will be impossible for him to pass his next physical, and that means an automatic sentence of death. It hurts her too much for her to watch him suffer any more; she’s convinced that any moment the truck from the Age Agency will be there to take him away.

The implications of this are clear for everyone. Barney’s time was limited anyway; he was the oldest of the group. The others, except for Annie (who has no desire to go on living without Barney) are under no immediate obligation; they still have some time left, and no matter what anyone says in the abstract, when the time comes, nobody really wants to die. However, they have always resolved that when it was time, they’d all go together; they’ve been together for too long, and waiting for Them to come and do the job would be an admission of defeat. They latch on the method of delivery: drugged whiskey, "Pills and liquor."

The final night becomes part wake, part elegy. Kate sums it up for the rest when they discuss the kind of message they want to leave if They ever read it. "That you fight for your humanity and dignity. That you refuse to be bent, folded, spindled, or mutilated by any machine. That you perceive and love the nature of the universe inside and outside of yourself." They say their toasts and drink their poison—and then, as they had wished, after they have lost consciousness Michael sets fire to the house and flees with the manuscript, delivering it to the underground. He had understood after all.

But—there’s one last tragic scene, one final ironic act. Because there could be no winner it a story like this, and how else could it end? For as They grew older ("deprived of their past," Mannes writes, "and fearful of their future."), They began to realize that Their laws, sooner or later, would apply to Them as well.

Thus, whether through enlightenment or self-preservation, the government had been toppled a few weeks before the final farewell, and the laws regarding age had been repealed.

III

"They," based on Marya Mannes’ controversial 1968 novel (and adapted by Mannes and Charles LeMay), originally aired on the Public Broadcasting Service’s NET Playhouse on April 17, 1970 as the final episode in an eight-part sub-series of plays titled "A Generation of Leaves," dealing with what was popularity known at the time as the Generation Gap. Jac Vanza, executive producer of NET Playhouse, described the central theme of all eight episodes as "the seemingly world-wide breach between youth and elders." "The younger generation questions its inheritance," said Vanza, "the older generation questions the values of the younger generation and herein lies the communications gap. Which is, by the way, nothing new."

Mannes’ didactic story of a man-made post-apocalyptic society is both simple and complex, and despite what some might thing, it defies pigeonholing into an easy category. For despite the similarities one might see with today’s cancel culture and the virulent fascism of many of today’s youth, this is not a one-sided conservative screed against the left. (After all, remember that the Patriot Act and the Department of Homeland Security were both products of a Republican administration.)

Mannes*, who described herself as a "liberal social critic" and was in agreement with many of the young in their attitudes toward the war, abortion, women’s rights, and other benchmarks of the left, denied that "They" should be seen as inherently anti-youth. "I am violently against the concept of a generation gap," she told one interviewer. "It is a losing game—everybody loses."

*Mannes should be no strager to readers here; she was a frequent contributor to TV Guide in the 1960s, observing the culural scene with a sharp eye and even sharper tongue.

Mannes*, who described herself as a "liberal social critic" and was in agreement with many of the young in their attitudes toward the war, abortion, women’s rights, and other benchmarks of the left, denied that "They" should be seen as inherently anti-youth. "I am violently against the concept of a generation gap," she told one interviewer. "It is a losing game—everybody loses."

*Mannes should be no strager to readers here; she was a frequent contributor to TV Guide in the 1960s, observing the culural scene with a sharp eye and even sharper tongue.

Indeed, Mannes approaches the story as a woman of the left, the old left, believing in discussion and debate and the free exchange of ideals and ideas. "What upsets me the most is the assumption that the world started in 1970, that there was nothing before," she said. "That one generation, they young, have a monopoly on religion, truth, courage. . . I think they’ve made it hard for themselves by deliberately antagonizing all others except themselves, by making of themselves a self-conscious, almost conformist power group. They talk about love a great deal, and it’s true among themselves, but they have very little love or tolerance not only to those older but to those who don’t go along with them."

Writing in The New York Times, Mannes shared her experience adapting her novel for the screen. "I was prepared to snip, inject, remove, amputate, drain and transfuse wherever necessary, anesthetizing myself rather than the patient when the pain began. What—cut that brilliant scene, that moving dialogue, that lovely appendix?" Not surprisingly, it is in the novel that we get the full effect of Mannes’ opinions on many of these issues. Not all of them have to do directly with the story, but they provide insight into her thoughts on contemporary issues.

For instance, she has nothing but distain for the dehumanization effects from the rise of computers and Artificial Intelligence: "The machines were part of the takeover, for they had invaded every function of daily life. We were told, of course, that the machine was still the servant of the man: that what you put into it determined what came out of it. And the simple fact was that when the programmers, in their new, special, and to us, totally incomprehensible language, fed their machines the plethora of data available on the old, out came the one recurrent and irrefutable answer: dispensable."

She also mocks the efforts of the old to be "with-it": "Older men, once handsome and secure in their gray or receding hair, dyed it or bought themselves toupees. Older women hiked their skirts above their knobby knees and had silicone pumped into their breasts or faces. To dress (unless they were rich enough to command their style) they were forced to dress like dolls because no clothes were made for women. The word had become obsolete: it implied maturity." "Our sin, she concludes, "was age."

Several times Mannes returns to the idea of the new generation as "barbarians": "Barbarians are essentially people without a past or a future, living entirely for the gratification of their immediate desires. They’re an aggressor, against language, sex, nature, love, art, life. The barbarian is a violator: the agent of violence." She adds, however, that none of this could have been possible with those in the older generation. "Don’t forget that a lot of this sort of crap was pushed on the public by people old enough to know better. Don’t blame Them if Their mini-talents were blown up out of all proportion. The cultural elite was so goddamn scared of missing the boat they’d ride on junk."

And in perhaps the most pertinent, most timeless comment of them all; one that could be applied to contemporary issues—forced equality, fraudulent egalitarianism, demanding an equality of results rather than opportunity, the culture of victimhood—she reminds us that "Democracy cannot survive without individual responsibility, and equality has never existed in the first place. Certain people are better than others and always will be, and it is only the barbarians who do not know this."

IV

The Who hoped to die before they got old. Mick Jagger called getting old a drag. Jack Weinberg warned us not to trust anyone over 30. They’re all well over that mark by now, though.

Although "They" is set in the near future (20 years from the date the novel was written), it is—unlike so many dystopian stories—most assuredly not science fiction. The setting, the clothes, the language, are all very much of our time; the few futuristic elements—whether technological (like computers and AI) or cultural, were already in the works by 1968, and Mannes’ predictions for their use in the future are disconcertingly on-target. Perhaps most disturbing is the idea that They came to power not through a revolution or a nuclear post-apocalyptic society, but from—an election. No, despite some surface similarities, I don’t think you can compare "They" to something like, say, Logan’s Run.

One of the most interesting aspects of "They" is the lack of religion. Mannes doesn’t make a big issue of this, other than to mention that none of these people saw themselves as "religious." There’s no discussion of any stand by religious leaders, any attempt to square the new laws that They create with the axioms of traditional religious faith; it simply isn’t a thing, and it that I suppose she’s presaging not only the advent of today’s millennials, but the lukewarmness of today’s faith. Remember the nearly worldwide shutdown of churches during the Covid lockdown? Remember how quickly so many of today’s religious "leaders" latched on to the mantra of the vaccine? Maybe they found a way to rationalize it all as well.

Nonetheless, Kate’s account, as presented in the novel, concludes on an intriguing note—a note of hope, a plea for help, perhaps born of faith, perhaps simply the need for comforting words. It’s the Libera me ("Deliver me") from the Catholic Office of the Dead. "Deliver me, O Lord, from death eternal on that fearful day/When the heavens and the earth shall be moved/When thou shalt come to judge the world by fire."

V

Reviews of "They" were mostly favorable; Donald Kirkley of the Baltimore Sun pronounced it "a plight to remember," and the Mansfield News-Journal called it an "enchanted visit with a group of veteran characters, played with taste and sensitivity by an eloquent cast of actors." The New York Times described it as "hauntingly effective and heartrending." "The cast was so excellent that it would be unfair to pick out one member over another. [Director Marc] Daniel effortlessly moved his company about the stage and through deft psychedelic electronics achieved the desired quality of eerieness to complement the human element."

It appeared to hit home with viewers as well, some of whom were left shaken by what they’d seen. Mary Ann Lee from the Memphis Press-Scimitar reported receiving one letter from a viewer comparing "They" to "a bad dream," and added "Such a world in 1990 would be worse than anything that comparative Pollyanna, H.G. Wells, ever dreamed up."

Percy Shain of the Boston Globe was less enthusiastic, finding that it was "chilling and well put, but failed to provide the dramatic tension necessary for a compelling experience." However, Shain may have inadvertently touched on the real message of the story when he wrote that "the concluding suicides were almost welcome." For in the world which Mannes had constructed, there could have been no other way; the lack of drama itself emphasizes the lack of options—the tragedy.

One critic remarked that "They" "had some telling things to say about the consequences of rudeness in the young and permissiveness by their elders—and about the new outlook that comes to a youthful rebel of 20 when he reaches 40." This is a perceptive comment as far as it goes, but it would seem that Their homicidal madness extends much farther than simple "rudeness."

The most ironic comment, however, came from a critic who commented that, "…if taken to an ultimate, ugly extreme, the society of They would not be impossible. I doubt, however, that even Miss Mannes believes it is probable."

I wouldn’t be so sure about that today. Nowhere in the world They created do we see or hear the word "fascism." It exists, though.

VI

José Ortega y Gasset, the Spanish writer and philosopher, warned in his 1930 book The Revolt of the Masses of the dangers inherent in the rule of a regime very much like the one They established. "As they say in the United States: 'to be different is to be indecent,' he wrote. "The mass crushes beneath it everything that is different, everything that is excellent, individual, qualified and select. Anybody who is not like everybody, who does not think like everybody, runs the risk of being eliminated. And it is clear, of course, that this 'everybody' is not 'everybody.' 'Everybody' was normally the complex unity of the mass and the divergent, specialized minorities. Nowadays, 'everybody' is the mass alone. Here we have the formidable fact of our times, described without any concealment of the brutality of its features.

He also describes the brutality of so many of today's youth, edgy teans turned radical students turned snowflakes, intolerant of any differing opinions, hatred burning in their eyes. "The Fascist and Syndicalist species were characterized by the first appearance of a type of man who 'did not care to give reasons or even to be right', but who was simply resolved to impose his opinions. That was the novelty: the right not to be right, not to be reasonable: 'the reason of unreason.' " Their opinions, of course, are the exception; they are always right. Error, they proudly declare, has no rights.

VII

The fact that 1990 came and passed without Mannes’ predictions coming to fruition—well, that really isn’t important. We’d already come to see the aged as a drain on society long since then, thanks to the breakdown in the family structure and the explosion in retirement communities, where Grandma and Grandpa could be shuffled off without too much thought. We stopped caring about them a long time ago.

As our economies continued to hemorrhage, and our foreign adventures became more frequent and more costly, we looked at how much it cost to take care of those who, if you’re being honest, contribute very little, at least as far as productivity was concerned. Social Security always seemed to be getting in the way of balancing the budget, and it was obvious that healthcare was one of those resources that was simply going to have to be rationed, and we had to make sure, after all, that the most productive members of society could continue to function, in order to create a new society, a pragmatic society, one built to meet the needs and withstand the pressures of a modern world.

Anyway, what about all the stress that people put on the planet, things like climate change and global warming and overpopulation and running out of clean energy alternatives? We hardly had enough food and clean water and land to go around now; how were we going to manage in the future, as the population grew older, unless we did something drastic?

The problem was there were too many parasites around: people who didn’t contribute, people who were, when you came right down to it, were just too expensive to take care of? Of course, we didn’t actually call them that, parasites; it wouldn’t have been polite, and we had to always take pains not to offend; but that’s what they amounted to, in our eyes: they took more and more, and contributed less and less, and it produced a model that was simply unsustainable for the future.

So we talked about things like "Quality of Life," and asked whether, if you couldn’t do the things you did when you were young, your life was really worth living? Therefore, assisted suicide—or euthanasia, as its proponents might prefer—was not only an act of mercy, it was really the only sensible thing for a responsible person, someone who cares about the next generation, to do, n'est-ce pas? A Final Solution, you might even say.

We created the computers that became part of our everyday life, and we dreamed about the day when they could think for themselves; "Artificial Intelligence," we called it. "We were told, of course, that the machine was still the servant of the man: that what you put into it determined what came out of it. And the simple fact was that when the programmers, in their new, special, and to us, totally incomprehensible language, fed their machines the plethora of data available on the old, out came the one recurrent and irrefutable answer: dispensable." And when enough people tell you that, you "become what others believe."

And we created things like lockdowns, where we isolated those that were most vulnerable, the sick and the elderly and the shut-ins, we understood that the deprivation of love, of human contact, would demoralize those who hadn’t already lost hope, would make them feel like outcasts. And we threatened others, those who didn’t follow the rules, with a different kind of isolation, for "the good of society." We knew just how potent that deprivation could be.

So here we are, in 2023. So They were late. Big deal.

At one point Lev remarks, "People do not really want change. They are told by a minority that they must have it, and then a minority fights for it—and the majority are changed."

Maybe, then, we don’t need to wait for Them to take over.

Maybe They already have. TV

So here we are, in 2023. So They were late. Big deal.

At one point Lev remarks, "People do not really want change. They are told by a minority that they must have it, and then a minority fights for it—and the majority are changed."

Maybe, then, we don’t need to wait for Them to take over.

Maybe They already have. TV

My thanks to Maureen Carney and Jodie Peeler for asssistance with images and other background material.

OTHER ENTRIES IN THIS SERIES:

Beautiful, important piece, Mitchell--thank you.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Paul - I really appreciate that!

DeleteDo you think that 1969's "The Lottery" would ever rate a review in this category. I don't care much for the name of the feature, but it does show how bad people can be and at times are unfortunately becoming.

ReplyDeleteThat's a good question. I don't think I'd do the 1996 version (although I'm saying this without having seen it, so I might change my mind), It's unfortunate the 1969 movie wasn't made for TV; if it had been, I think I might. I could still change my mind, though - thanks for putting the thought in my head.

Delete